When “Relationship-Centred” Isn’t Enough

On Slogans, Silence, and the Work That Still Needs Doing

A viral meme claims education is “relationship-centred”—but what happens when the system excludes you? This piece explores what real connection requires, and what we build when the system offers only slogans.

Introduction

It always starts with a meme…

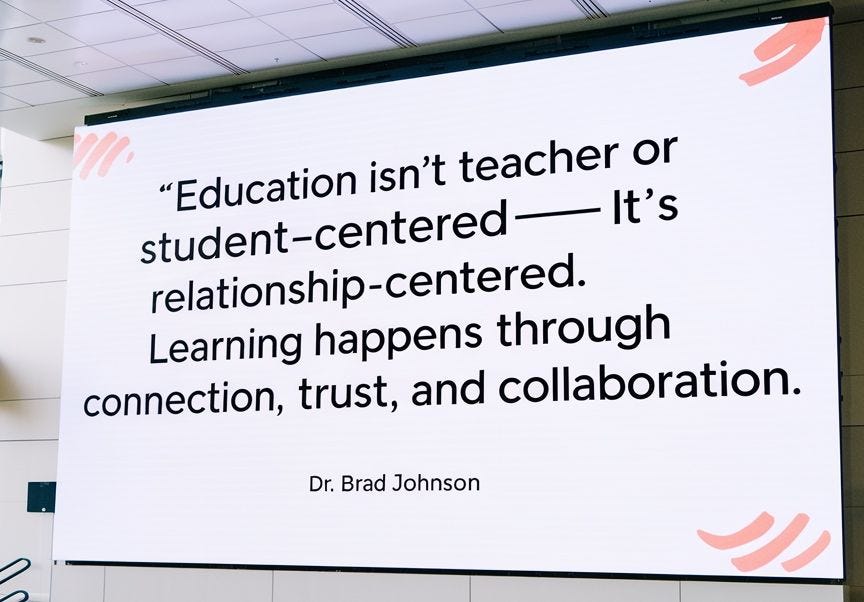

This time, it was a quote attributed to “Dr. Brad Johnson,” floating across my feed in the usual stylised package: elegant serif font, warm cream background, the subtle visual cue that this is meant to feel wise and gently affirming. “Education isn’t teacher- or student-centred,” it proclaimed. “It’s relationship-centred. Learning happens through connection, trust, and collaboration.”

At first glance, it reads as harmless — even comforting. Who among us would argue against the importance of connection in learning spaces? And yet, like so many viral sentiments passed around LinkedIn, it’s a polished surface stretched over a hollow centre. What looks like wisdom is, in fact, a quiet act of misdirection.

For context, Dr. Brad Johnson is a former military officer turned educational consultant and motivational speaker, known for authoring several books about leadership in schools. His posts often perform well on social media because they traffic in a certain tone — emotionally resonant, easily digestible, non-confrontational. They’re tailor-made for “likes” and shares among school leaders and HR professionals. His brand of insight fits perfectly into the LinkedIn ecosystem, which rewards the appearance of emotional intelligence over the substance of systemic critique. It feels profound without ever threatening the status quo.

But if you’re someone who has lived through the very systems these posts aim to inspire — someone on the margins of the educational experience, as I am — this kind of content becomes difficult to engage with uncritically. It’s not that the quote is wrong, exactly. Connection, trust, and collaboration do matter. The problem is how this framing erases structural violence and reframes failure as a personal shortcoming. If students aren’t learning, if things aren’t going well in the classroom, well… perhaps you didn’t build the right relationship. Perhaps you, the teacher, didn’t connect hard enough. Didn’t try enough. The system is never interrogated — only the individual.

And for those of us who are autistic — especially those of us with hyper-empathy and alexithymia — this message lands with particular cruelty. We are often keenly aware of emotional dynamics, even as we struggle to identify or name our own emotional states. We sense when something is wrong, when the relationship is performative, when the classroom is not a safe space — even if we can’t always say so out loud. And in these spaces, the idea of “relationship” becomes less a bridge and more a cudgel. A way to blame those of us who already feel too much for not fitting into a script that was never written for us.

I’ve spent years trying to unpick these dynamics — as a student, as an educator, and as someone who has always existed slightly outside the frame. This article isn’t just a reaction to a meme. It’s a response to the broader pattern that meme represents — the way the education system dresses up systemic harm in the language of warmth and care, all whilst demanding that we ignore the structural roots of exclusion. My work, both in and beyond the classroom, has followed a different pattern — not one of easy connection or compulsory trust, but of recognising harm, questioning whether it’s just me, listening to others, identifying systemic failure, and then building what didn’t exist. That’s not something a viral quote can fix. But it’s where the real work begins.

A Different Pattern: How I Actually Learn and Create

The reality is, I don’t learn through slogans. I’ve never been able to. Shallow optimism doesn’t hold up in a world that so often treats people like me — autistic, trans, traumatised — as inconvenient reminders that the system isn’t working. So when I think about how I’ve actually come to understand the world, how I’ve made sense of harm and then found ways to respond to it, what emerges is a very different pattern from the one implied by tidy social media wisdom.

It’s a pattern I didn’t set out to formalise, but one I now recognise clearly in my own process — and in the quiet work of so many others pushed to the edges of institutions that were never built with us in mind. It goes like this:

Recognising harm — not always instantly, not always with clarity, but feeling it first, usually in the body. A sense of wrongness. A tightening. A subtle withdrawal.

Wondering if it’s just me — the self-doubt phase, shaped by a lifetime of being told I misread situations, or that I was too sensitive, or not professional enough, or simply too much. The gaslighting phase, internalised.

Researching others’ experiences — seeking resonance, reaching out into the shared space of lived experience. This is where the loneliness breaks open and reveals solidarity. Forums. Articles. Conversations after hours. The pattern begins to surface.

Discovering systemic patterns — connecting the dots between individual stories and structural realities. Seeing that what looked like a personal failure was in fact a design feature of the system. Not an accident. Not a one-off. A recurring motif.

Writing toward both understanding and creating alternatives — not just naming the harm, but building from it. Writing to make sense of the world, to offer scaffolds where there were none, to put shape around pain so others might not have to go through it alone.

This is my professional development. This is my research methodology. This is how I know what I know.

And it stands in stark contrast to the simplified vision offered by memes like the one that sparked this reflection. That version of education — where “connection” is a cure-all, and learning flows naturally from mutual trust — is neat, tidy, and appealing. But it’s also incomplete. Because it asks nothing of the system. It demands only that the individuals within it perform better. Trust more. Collaborate harder. Build the relationship, no matter the conditions.

My pattern doesn’t offer a quick fix. It’s not meant to. It’s messy and iterative and rooted in reality. But it has led me to real insight, real solutions, and real acts of creation — not because I was told to “focus on relationships,” but because I refused to accept a broken system as the only available option.

The UX of Exclusion: When 'Relationship' Is a Broken Interface

When I think about why that meme hit such a raw nerve, it’s because I’ve lived the contradiction it conceals. I’ve sat in classrooms where the so-called “relationship-centred” model fell apart the moment I walked in — not because I didn’t want to connect, but because the very structure of the space made connection impossible. For me, the problem has never been about willingness. It’s been about interface — the underlying design of the learning environment and whether or not it recognises, accommodates, and affirms my neurotype.

I first attempted to return to formal education around 2003. At the time, I was working in civil service — a post-9/11 moment when the city workforce was changing. The old guard, many of them Vietnam vets, were starting to retire, and newer hires like myself — Gen X, self-taught, and holding an ad hoc AA cobbled together from years of college credits — were being told that the future would require degrees. A bachelor’s to promote. A master’s to manage. Possibly even more.

Despite the fact that I was earning far more in overtime than any baseline salary could offer, I knew that the clock was ticking. If I didn’t future-proof myself, I’d be locked out of advancement. But I was also autistic, functionally illiterate in the eyes of academic systems, and terrified. I enrolled at the local community college. I lasted one day. The UX — the user experience — was atrocious. Cold, chaotic, overwhelming. I withdrew and tried again the next term. Same result.

I began to wonder if it was them or me. Maybe I just wasn’t cut out for higher education. Maybe the problem was internal, and all the fears I carried about being broken or incapable were true. But something in me held on. I found another local college and tried a few ‘easy’ classes. Again — the space didn’t make sense. The interface was hostile. No one seemed to understand how to structure learning in a way that invited people like me in.

Then, in 2006, I saw a flyer taped to the wall in my shop — a cohort-style BA programme in organisational leadership, held in a conference room at Sheriff’s Headquarters. It was a partnership with a well-regarded local university, heavily subsidised by the county, and the entire degree would cost under $10,000. More importantly, the space made sense. It was familiar. Predictable. I knew the building. I knew how to get there. I wouldn’t have to fight the noise, the architecture, the bureaucracy. I signed up — and for the first time, I didn’t withdraw.

What made that programme work wasn’t a special relationship with a particular teacher or a breakthrough moment of classroom bonding. Quite the opposite. It was the design. It was the way the environment — the interface — respected how I process information. It didn’t demand I become someone else in order to participate. It gave me the conditions I needed to succeed.

That experience became the seed of what would eventually become my doctoral dissertation. I didn’t pursue a PhD in education because I wanted a title. I pursued it because I saw, again and again, how poor educational design was misinterpreted as individual failure. And I wanted to understand how we might redesign learning environments so that students like me — students written off as too much, too little, too different — might actually have a shot. Not through magical relationships, but through intentional, inclusive architecture.

Credentialism, Harm, and the Neurodivergent Workforce

As my career in forensic science progressed, especially in the digital and multimedia space, I began to notice something quietly remarkable — a pattern that few people outside the field seemed to see. So many of the best analysts I met, those with an almost intuitive grasp of complex systems, those who could pull signal from noise in ways that defied training manuals, were neurodivergent. Some identified openly as such. Others didn’t have to — we recognised one another instinctively. The pattern was unmistakable: the very traits that made us feel like outsiders elsewhere were the same traits that gave us an edge in this highly specialised, often abstract field.

But alongside that brilliance, I also saw something else: fear.

By the early 2010s, a shift was underway. Agencies were beginning to talk openly about raising the educational bar. Where a high school diploma or some on-the-job training had once been enough to build a career, now the narrative was changing: a BS to do the work, an MS to supervise it, and increasingly, a PhD to testify in court as an expert witness. The conversation moved from informal chatter to official language. And the fear among my colleagues — those who had built their careers through skill and perseverance, but who had barely survived traditional education systems — was palpable. They knew what returning to school would mean. They knew how badly it had gone the first time. And they knew that, in this new landscape, their expertise might no longer be enough to keep their jobs.

I understood their fear intimately — because I had lived it. I had started my own academic journey not from a place of aspiration, but as an act of survival. I saw the credentialist future coming, and I knew that if I didn’t move quickly, I’d be cut out of the very work I had helped to shape. Earning my degrees — the BA, the MA, the PhD, and eventually a second MA in Instructional Design — wasn’t about chasing prestige. It was about preserving access. It was about building a path that others could follow, especially those who couldn’t yet see a way through the tightening educational demands.

For me, credentialism was never a ladder. It was a closing door I refused to let lock behind me.

And it wasn’t just about my own career. I kept thinking about those colleagues — brilliant, neurodivergent minds, barely holding on — and about what the field would lose if they were pushed out. The loss would be immeasurable. Not just in talent, but in perspective, in ways of thinking that couldn’t be taught but were desperately needed. What we were witnessing wasn’t professionalisation — it was gatekeeping. A system redesigning itself to reward conformity over innovation, compliance over lived expertise.

This recognition deepened my commitment to education, not as a personal achievement, but as a strategic intervention. If the system now required credentials to create, validate, or teach, then I would earn them — not to fit in, but to hold open space for those who couldn’t. My degrees became tools. Not weapons, not trophies, but keys — to unlock, to defend, to build.

Induction and the Myth of the “Relationship-Centered” Teacher

Now, as a teacher, I find myself once again facing a system that dresses expectation up as encouragement — and punishment as professional development. In California, the path to becoming a permanent educator is long, costly, and fraught with hidden trials. First comes the internship, often during the most precarious phase of one’s teaching life — underpaid, under-supported, and held to the same standards as seasoned colleagues. Then, after that first hurdle is cleared, induction begins soon thereafter. It’s meant to be a guided, reflective process — a two-year mentorship model intended to support new teachers as they grow into their roles. In practice, however, it functions as a high-stakes performance review stretched out across multiple years. And if you don’t complete it successfully within five years of your internship’s end, your credential expires. You’re done. Out of the profession. No do-overs.

It’s a trial by ordeal — a bureaucratised “proof of practice” in which you are asked, again and again, to reflect, document, and justify your teaching. And woven through the entire process is the insistent hum of a single, unspoken narrative: if your students aren’t thriving, perhaps your relationships aren’t strong enough. The same energy as that meme. The same logic that told me, earlier in my career, that if I wanted to keep working, I had better collect degrees — not because they made me better at the job, but because they made me acceptable to the system.

Induction, like much of the professional development that surrounds it, is built on the assumption that teachers are passive recipients of knowledge. The structure doesn’t ask what I’ve created, what I’ve built, what I’ve contributed to the field. It asks what I’ve consumed. What workshops I’ve attended. What frameworks I’ve aligned with. What boxes I’ve ticked. There is no room in the official narrative for those of us who develop resources rather than simply implement them. The system is not designed to recognise teachers as thinkers, designers, or knowledge-producers. It is designed to ensure conformity — to train educators to behave as loyal agents of a system that is deeply suspicious of originality, especially when it comes from the margins.

And so again, I see the same pattern I saw in forensics. A field that purports to value human connection and real-world insight, whilst quietly erecting barriers that exclude the very people most capable of offering both. Expectation without infrastructure. Pressure without support. A vision of success that demands full alignment, yet offers no space for difference.

Induction says it’s about growth, but it’s really about surveillance. It tells us to reflect, but only within the limits of its own vocabulary. And when it asks about our future professional development, it doesn’t ask what we plan to create — only what we’ll attend. What we’ll complete. What we’ll consume.

It’s not relationship-centred. It’s compliance-centred, couched in the language of care. And for those of us who already feel the burden of otherness in every room we enter, that contradiction is not just frustrating. It’s exhausting.

The Hidden Labour of Neurodivergent Teachers

For autistic teachers — especially those of us carrying both hyper-empathy and alexithymia — the labour of “relationship-building” as framed by the system isn’t just difficult. It’s dangerous. We’re not just working to form connections. We’re managing a constant, internal collision between feeling everything and being unable to name or source it. That contradiction alone is exhausting. But in environments that demand visible, performative rapport — warm smiles, spontaneous check-ins, the casual camaraderie of neurotypical bonding — it becomes unsustainable.

The system doesn’t see the cost. It only sees whether we’re performing the expected emotional gestures. Whether we’re making connections in the way it deems legible. But for someone like me, who absorbs every emotional frequency in a room without always knowing how to regulate what comes next, this is where burnout begins. Not with paperwork. Not with the hours. But with the constant demand to pretend that connection is possible in spaces where it’s not.

I’m not bad at relationships. I’m bad at faking them. I can’t do the scripted smiles or the emotionally loaded small talk. I can’t force myself to bond with someone who clearly doesn’t see me — or worse, who only engages with me as a compliance mechanism. And yet, because the system assumes that “relationship-building” is a neutral act, it punishes those of us who approach it differently. Who need time, context, trust, and reciprocity. Who cannot, and should not, spend every day borrowing spoons from some distant, unknown future just to stay afloat.

This is the hidden labour of neurodivergent teachers (aka, the autism tax). It’s not just the effort of teaching. It’s the effort of appearing emotionally fluent in a system designed by and for people whose relational frameworks often feel hollow or extractive to us. It’s the constant vigilance — the self-checking, the internal audits, the second-guessing — to make sure we’re not being gaslit by the system, or worse, gaslighting ourselves into believing we’re the problem.

The truth is, I feel deeply. Often unbearably so. That’s what hyper-empathy does — it floods the senses. I can feel the distress in a student long before it shows up in behaviour. I can read the emotional currents in a staff meeting like radar, even as I sit stone-faced, trying not to let it overwhelm me. But when I try to name my own emotional state, I often come up blank. The words aren’t there. The labels don’t stick. That’s alexithymia, made entirely more debilitating as a GLP. And when you live at the intersection of these, it creates a paradox that most people can’t see — until the burnout hits.

And it always hits.

Not just for me, but for so many of us. We call it burnout, but it’s more than that. It’s erosion. It’s what happens when every day requires more emotional labour than we can safely give, in environments that misread our exhaustion as indifference. The system sees a teacher who’s withdrawn, flat, maybe even uninvested. But underneath that, there’s someone who has felt too much for too long, with no space to process any of it. Someone who is holding it all together with threadbare string and borrowed spoons, while still being told to “build better relationships.”

What we need isn’t more pressure to connect. We need spaces that are safe enough, slow enough, and true enough to allow real relationships to form. Because when we do connect — when we’re seen, respected, and allowed to show up fully — the depth of our relationships is profound. But until then, we survive. We withdraw. We conserve. Not because we don’t care — but because we do, too much.

Refusal as Creation: From Systemic Harm to Authentic Solutions

Every time I return to that five-step pattern — recognising harm, wondering if it’s just me, researching others’ experiences, discovering systemic patterns, writing toward both understanding and creating alternatives — I see the throughline of my life’s work more clearly. It’s not a cycle of complaint. It’s a blueprint for creation. My response to systemic harm has never been retreat. It’s been authorship.

When the system leaves no space for people like me, I don’t wait for permission to exist. I build what’s missing.

And the work I’ve built — the books, the frameworks, the curriculum — they’re not extracurricular. They’re not passion projects or weekend hobbies. They are my professional development. They are my resistance, my offering, my attempt to make something more human, more useful, more real than the forms and trainings that have never fit.

No Place for Autism? was born out of the vacuum in teacher training around neurodivergent experience — a text written not from theory but from the raw edge of lived contradiction, as an autistic educator being bullied in a system that claimed to be inclusive.

Holistic Language Instruction followed, growing from the total erasure of gestalt language processors in every ELD and literacy space I entered. It was a refusal to let these students — students like I once was — be pathologised out of their own communication.

Decolonising Language Education emerged from the pattern I saw in my own classroom: children navigating a school system that treated English not as a bridge, but as a border. That text exists because the damage done by monolingual pedagogy demanded to be named.

And then there’s The Story of Math, the project currently underway. A full-year curriculum built not around testable skills but around coherence, narrative, and human belonging. A maths book written for the very students most curriculum leaves behind — those with IEPs, with interrupted education, with stories the pacing guide doesn’t account for.

None of these projects came from above. No administrator assigned them. No credentialing body suggested them. They came from the margins. From my pattern. From seeing something that wasn’t working, and instead of waiting for it to be fixed, deciding to build the thing myself.

This is what professional development looks like for someone like me. Not a checklist of trainings completed or frameworks internalised, but a series of artefacts — living documents, responsive texts — created in response to harm, and shaped by the desire to offer something better. Something usable. Something real.

These projects aren’t peripheral to my teaching — they are my teaching. They are what I bring to the table. They are the way I continue to show up, even in a system that wasn’t made for me. And they are the clearest evidence I have that what gets dismissed as “noncompliance” is often just unrecognised leadership.

Final thoughts …

In the end, I find myself circling back to that meme — that deceptively warm message floating across LinkedIn: “Education isn’t teacher- or student-centred. It’s relationship-centred. Learning happens through connection, trust, and collaboration.” It’s the kind of sentiment that gets shared and reshared by people who, I believe, mean well. But for those of us living and working at the edges of this system — neurodivergent, disabled, queer, trans — it rings hollow. Worse than that, it becomes a kind of weapon. A quiet accusation dressed as inspiration.

Because here’s what the meme gets wrong:

You can’t build trust in a space designed to exclude.

You can’t force collaboration in an architecture of compliance.

You can’t measure connection with a rubric.

What’s being offered in that quote is not a model for learning. It’s a branding strategy — a superficial script for a system that still refuses to confront its own design flaws. It assumes that relationships are always possible, always symmetrical, always healthy — and that if they’re not, the fault lies with the individuals within the system, not the system itself.

But I know better. I’ve lived better. I’ve seen the difference between performative connection and real belonging — and I’ve learned that the former exhausts me, whilst the latter sustains me.

Real relationships — the kind that actually support learning — are not built on slogans. They are built on care. On coherence. On co-creation. They require spaces where people can show up fully, without having to amputate parts of themselves to make others comfortable. They require time, trust, and shared power. And they are impossibly rare in systems that still mistake standardisation for equity and performance for growth.

So when those spaces don’t exist — when the architecture remains hostile, when the doors stay shut — we build something else. We refuse the script and write new ones. We map new paths. We gather in the margins and make something that works. Something that speaks our language. Something that welcomes those who’ve never seen themselves reflected in the system’s vision of success.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s the most important relationship of all — the one we build with ourselves, with our communities, with the work that calls us to keep going. Even — and especially — when the system forgets we’re here.