This article introduces Able Grounded Phenomenology, a transformative, anti-colonial framework that critiques and disrupts traditional autism research. It explores AGP’s principles, its real-world application, and the urgent need for its adoption to ensure justice and meaningful change.

Introduction

Autism research has long been plagued by systemic problems that undermine its ability to truly serve the Autistic community. Dominated by a deficit-based framework, much of this research operates on the assumption that Autistic traits are flaws to be corrected rather than natural variations of human experience. This lens not only pathologises Autistic individuals but also shapes interventions that prioritise conformity to neuro-majority norms over the well-being and authenticity of Autistic lives. Furthermore, Autistic voices remain largely excluded from the research process, leaving the lived experiences of those most impacted undervalued and ignored in favour of outsider perspectives.

As an autistic researcher and Chair of an autistic founded and led independent Institutional Review Board (IRB), I have witnessed firsthand the harm caused by these entrenched practices. Research should be a tool for understanding and improving the lives of those it seeks to study, yet too often, it is co-opted to generate ‘evidence’ for one capitalist solution or another, operating under some of the loosest guidelines for what qualifies as evidence in the world, particularly here in the US. My experiences navigating these systems have given me a unique perspective on the importance of ethical frameworks that prioritise Autistic participation and centre our voices in the conversation.

Able Grounded Phenomenology (AGP) offers a way forward. Developed by Dr. Henny Kupferstein, this framework challenges the traditional pathology-focused approach to autism research, providing a transformative tool for ensuring ethical, inclusive, and respectful studies. By reframing autism research to align with neurodiversity principles, AGP disrupts harmful narratives and opens the door to a more humane and authentic understanding of Autistic lives. It is within this context that I will explore the necessity of AGP, using both its foundational principles and real-world application to illustrate why its adoption is essential.

Able Grounded Phenomenology and Its Creator

AGP is a framework designed to bring ethical integrity and inclusivity to autism research, a field often mired in dehumanising practices and reductive assumptions. At its core, AGP centres Autistic voices, lived experiences, and strengths, rejecting the deficit-based medical model that frames autism as a problem to be solved. By prioritising respect for neurodivergent ways of being, AGP ensures that research reflects the needs and perspectives of those it seeks to benefit, rather than perpetuating harmful narratives or misguided interventions. Its principles challenge researchers to engage in practices that are not only scientifically rigorous but also socially and morally responsible.

AGP was developed by Dr. Kupferstein, an autistic humanistic psychologist and advocate for neurodiversity. Her journey, shaped by her lived experience and her professional expertise, led her to create AGP as a direct response to the systemic issues within what many term the “Autism Industrial Complex.” This complex, driven by capitalist interests, prioritises profit over the well-being of Autistic individuals, channelling vast amounts of funding into research that reinforces damaging stereotypes or yields little meaningful benefit. Dr. Kupferstein’s work stands as a testament to the power of reclaiming the narrative, crafting a research framework that centres humanity, authenticity, and justice.

The urgency for AGP cannot be overstated. Traditional autism research paradigms have roots in colonial and eugenic practices, treating Autistic individuals as objects to be studied and controlled rather than as collaborators with agency and insight. These paradigms have perpetuated a cycle of studies aimed at erasing or “correcting” Autistic ways of being, prioritising conformity to the neuro-majority’s norms over the lived realities and needs of Autistic people. Such research often frames autism as a deviation to be normalised, mirroring the historical efforts of colonisers to assimilate and suppress cultural difference. AGP offers a crucial break from this harmful legacy, aligning with neurodiversity principles and insisting that Autistic individuals must be active participants in research that shapes our lives. It reimagines the purpose of autism research, steering it away from the pursuit of normalisation and toward a genuine understanding of, and meaningful support for, Autistic ways of being.

Critiquing Traditional Autism Research

In a previous article, I explored how traditional autism research often operates within a deficit-based framework, assuming that Autistic traits are abnormalities to be corrected rather than natural variations of human experience. This framing perpetuates the idea that Autistic people are fundamentally broken, requiring interventions to "fix" them or align them with neuro-majority expectations. As I highlighted in that analysis, this approach fails to account for the broader context of power, relationships, and societal pressures that shape our understanding of autism. It prioritises conformity over authenticity, reinforcing the harmful belief that Autistic ways of thinking, feeling, and interacting are inherently inferior.

One case study I examined was the Emotional Recognition Memory Training Program (ERMTP), which exemplifies the flaws of this approach. Designed to address supposed deficits in “cognitive empathy” and “emotional arousal,” the study relies heavily on parent-reported outcomes, a tiny sample size, and deficit-oriented goals that prioritise teaching Autistic children to perform neurotypical behaviours. The study’s design itself is riddled with methodological flaws: the absence of randomisation and control groups undermines its reliability, whilst the cultural pressures in its setting (Thailand) further skew its findings. In a society where conformity is highly valued, parents may feel compelled to over-report positive changes, making the study’s outcomes more reflective of societal expectations than genuine “progress.” Moreover, the inclusion of non-Autistic children alongside Autistic participants creates a comparison that risks framing Autistic ways of being as deviations to be eliminated rather than particularly valid human responses and actions.

The ethical implications of research like ERMTP are profound, as I previously discussed. Interventions of this kind are not merely neutral tools—they actively promote masking, a behaviour where Autistic individuals suppress our authentic selves to appear more neurotypical. Masking, as I’ve noted, is widely documented to cause significant long-term harm, including anxiety, burnout, and a diminished sense of identity. By encouraging conformity to neuro-majority standards, studies like ERMTP perpetuate systemic harm, framing the problem as lying within the Autistic individual rather than within the societal structures that demand such conformity. Instead of fostering acceptance and accommodation, this research reinforces the oppressive notion that Autistic lives are only valuable when moulded to fit a neurotypical ideal. This is precisely the kind of harm that Able Grounded Phenomenology seeks to disrupt, offering a framework that centres authenticity and respect over conformity and erasure.

The ‘Consumer Audit’ Paper as an Exemplar of AGP

Kupferstein et al.’s audit of the UC Davis MIND Institute provides a compelling case study in the application of Able Grounded Phenomenology and offers a scathing critique of how autism research is conducted under the banner of the “Autism Industrial Complex.” The paper examines a study using genetically modified mice to model Angelman Syndrome and links this research to Autism through speculative claims about its “translational value.” This audit reveals that the MIND Institute’s approach to autism research aligns more closely with the interests of capitalism than with the genuine needs of the Autistic community. Funded by mechanisms such as the Autism CARES Act, the institute exemplifies the way research institutions can act as engines of the “Autism Industrial Complex,” generating “evidence” to sustain themselves and their funding pipelines rather than producing meaningful advancements for Autistic people. The result is a system that privileges profit and prestige over genuine impact, turning research into a grift rather than a service to the community.

The audit uses AGP to expose these systemic failures, offering a framework that centres ethical considerations and Autistic lived experience. Specifically, AGP guided the authors in evaluating the study’s reliance on animal models, which they argue are wholly inadequate for understanding autism, a way of being rooted in human neurodevelopment and social contexts. The study's focus on mouse gait patterns as an analogue for “behavioural and cognitive abnormalities” in Autism exemplifies the speculative nature of much of this research. AGP calls for rejecting these dehumanising approaches, insisting that autism research must involve Autistic individuals as collaborators, not as abstract constructs or subjects to be studied from a distance. By applying AGP’s principles, Kupferstein et al. demonstrated how the MIND Institute’s work fails to meet even the most basic ethical standards for research involving marginalised human populations.

A key strength of AGP is its insistence on interrogating the flow of funding and the power dynamics embedded in research design. The audit highlights how public funds, often justified under the guise of supporting Autistic individuals, are diverted into speculative projects like this one, which yield little practical benefit. The authors critique how the medical pathology paradigm, which frames autism as a disorder needing a cure, shapes the research agenda and funding priorities of institutions like the MIND Institute. This approach not only dehumanises Autistic people but also perpetuates a cycle where funding supports studies that align with capitalist interests—such as the development of therapies or interventions aimed at “normalising” Autistic traits—rather than addressing the actual needs of the Autistic community. AGP disrupts this cycle by demanding transparency, accountability, and a clear link between research outcomes and tangible benefits for Autistic individuals.

The findings and recommendations of the audit are unambiguous. Kupferstein et al. call for a complete re-evaluation of how autism research is conducted and funded, urging institutions to move away from speculative animal studies and deficit-based frameworks. They advocate for the reallocation of funds towards community-led research that centres Autistic voices, priorities, and well-being. This includes a legislative push to ensure that public funds earmarked for autism research are used in ways that directly benefit the Autistic community, rather than supporting the Autism Industrial Complex. By highlighting the MIND Institute’s failure to uphold ethical standards and produce meaningful outcomes (I would add, yet again), the audit serves as a wake-up call for the broader research community. It demonstrates how AGP can be used as a tool not only to critique harmful practices but also to propose a path forward—one that centres humanity, respect, and justice in autism research.

The Incestuous Nature of Autism Research

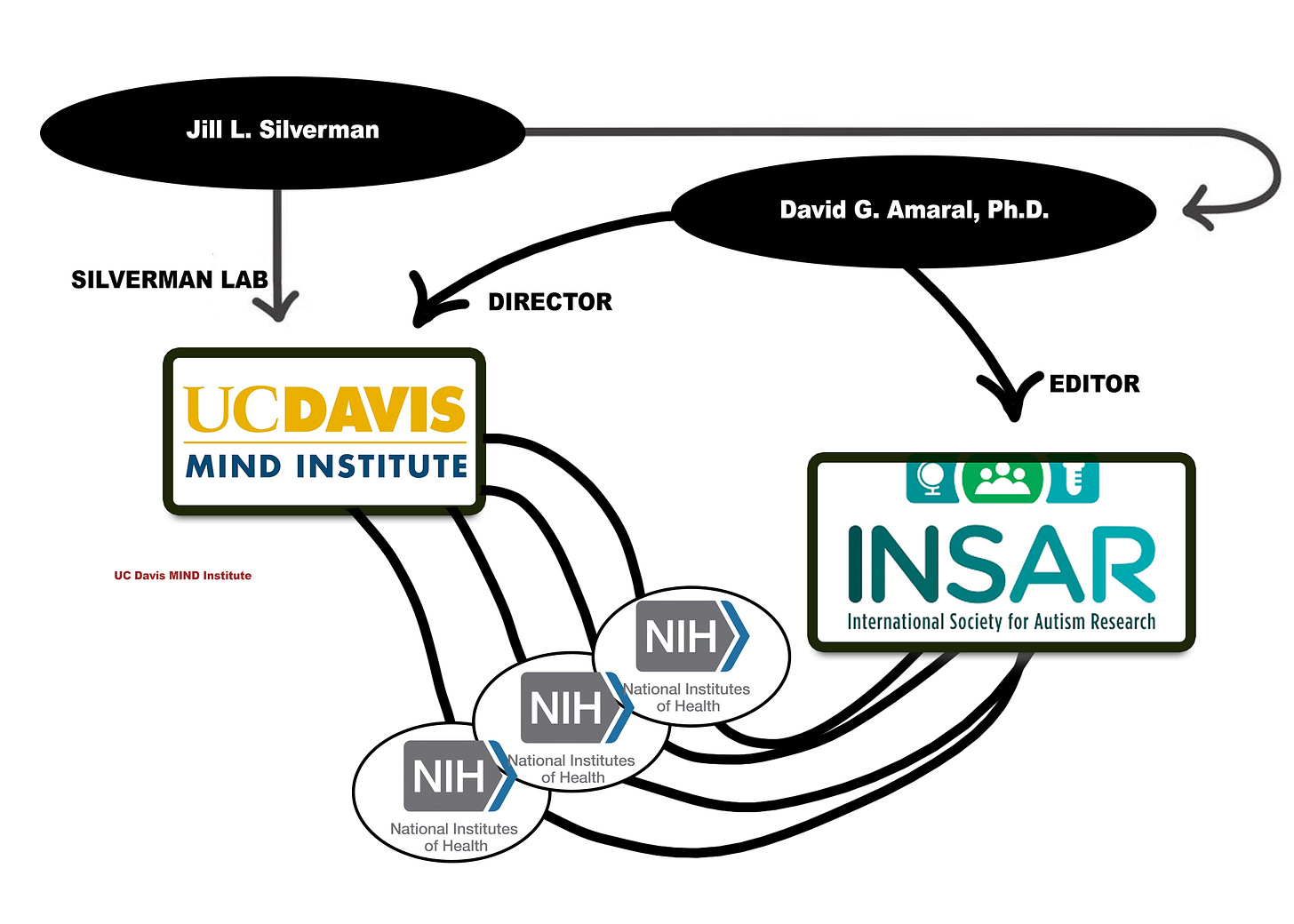

The infographic from Dr. Kupferstein’s consumer audit page provides a stark visual representation of the deeply intertwined relationships that define the Autism Industrial Complex. It illustrates how funders, researchers, and institutions form a self-sustaining ecosystem, where priorities are shaped more by capitalist incentives than by the needs of the Autistic community. Large funding bodies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), allocate grants that perpetuate a narrow, deficit-based framing of autism. These funds flow into institutions like the UC Davis MIND Institute, which, in turn, conduct research that reinforces the narratives favoured by their funders. Publications in high-profile journals often emerge from these studies, not to advance meaningful understanding, but to generate further funding opportunities. This cycle of mutual reinforcement prioritises institutional survival and prestige over ethical considerations or meaningful outcomes for Autistic individuals.

This system thrives under capitalism, where autism research has become commodified and serves the profit-driven goals of the Autism Industrial Complex. The commodification of autism can be seen in the proliferation of “therapies,” “interventions,” and pharmaceutical “solutions” marketed to parents and schools as essential tools for “managing” autism. These products often emerge from the same institutions depicted in the infographic, creating a feedback loop where research is shaped to justify existing capitalist solutions, all while there remains a glaring disparity between the vast amounts of funding poured into such research and the limited resources allocated to directly support Autistic people and their families. Capitalism’s influence ensures that research topics are chosen not for their relevance to Autistic lives but for their potential profitability or alignment with the deficit-based medical paradigm. The result is an entire industry built on exploiting Autistic individuals under the guise of support, while rarely involving us in any meaningful way (once again, we see capitalism being capitalism - exploitation is a feature, not a bug).

AGP offers a necessary and radical disruption to these exploitative cycles. By demanding transparency, community-led priorities, and a commitment to ethical integrity, AGP directly challenges the incestuous relationships depicted in the infographic. Unlike traditional research paradigms, which centre institutions and their funders, AGP centres Autistic voices and lived experiences, ensuring that research reflects the needs and values of the community it claims to serve. AGP rejects the commodification of autism, focusing instead on fostering understanding, acceptance, and meaningful support. It insists that research outcomes be judged not by their ability to generate profit or prestige but by their capacity to improve the quality of life for Autistic individuals.

Through the lens of AGP, the relationships highlighted in the infographic reveal their true nature—not as collaborative partnerships advancing scientific knowledge, but as a system of mutual reinforcement designed to sustain the Autism Industrial Complex. This critique calls for a fundamental shift in how autism research is conceptualised and conducted. It requires dismantling the structures that prioritise capitalist gain over community well-being and replacing them with frameworks like AGP that centre humanity, respect, and justice. By doing so, we can move toward a research landscape that genuinely serves Autistic individuals rather than exploiting them as commodities in a deeply flawed system.

Final thoughts …

The conclusion of this analysis demands a clear call to action: the widespread adoption of Able Grounded Phenomenology is not just necessary for ethical autism research—it is essential as an anti-colonial intervention. Autism research, as it stands, operates as a colonial enterprise, with researchers and institutions acting as imperial ground forces, imposing their deficit-based narratives, interventions, and “solutions” upon the Autistic population. In this framework, Autistic individuals are akin to an indigenous population, our authentic ways of being pathologised and exploited for profit, whilst the research-industrial machinery thrives at their expense. This system is not an aberration; it is the logical outcome of a capitalist structure that prioritises commodification, conformity, and control over the dignity and self-determination of marginalised groups. AGP, therefore, is not merely a framework for better research—it is a vital tool in the decolonial toolkit, one that seeks to dismantle the colonial logic underpinning the Autism Industrial Complex.

To embrace AGP is to reject the colonial mindset that defines autism research today. It is to insist that research must centre Autistic voices and lived experiences, recognising them not as data points to be mined but as vital perspectives that must drive inquiry and outcomes. AGP demands that we move beyond the framing of autism as a problem to be solved and instead see Autistic ways of being as valid, valuable, and deserving of respect. This shift is inherently anti-colonial, challenging the imperialist structures of power and profit that have shaped autism research for decades. It confronts the capitalist system that views Autistic individuals as commodities to be studied, fixed, and marketed to, rather than as people with agency and intrinsic worth.

The need for this decolonial approach becomes even more urgent when we consider how deeply intertwined autism research is with capitalism. The systemic exploitation of Autistic individuals is not a by-product of capitalism—it is a deliberate feature. The Autism Industrial Complex thrives on creating interventions, therapies, and treatments that perpetuate the deficit narrative, ensuring a continuous market for its products and sustaining the funding pipelines that power its institutions. This system cannot be reformed through minor adjustments or superficial shifts in language. It must be dismantled, and AGP provides a framework for doing so by prioritising transparency, accountability, and the empowerment of the Autistic community.

In reflecting on this, it is clear that AGP represents more than just a methodological framework—it is a call to reimagine autism research as a practice rooted in respect, justice, and solidarity. It asks researchers to take responsibility for the harm their work has perpetuated and to commit to a future where research serves Autistic people rather than exploiting us. It challenges us to envision a world where Autistic authenticity is celebrated, not erased, and where the well-being of Autistic individuals is placed above the pursuit of profit and prestige.

The adoption of AGP is not simply a moral imperative; it is a necessary act of resistance against the colonial and capitalist structures that have defined autism research for far too long. It is a tool for liberation, a means of dismantling the systems that oppress and commodify, and a pathway to a research landscape that is truly inclusive, ethical, and just. Let this be the starting point for a broader movement to decolonise not just autism research, but the ways in which we think about and engage with all marginalised populations. The time for change is now. AGP shows us how to begin.