Where's the science in the Science of Reading?

The latest edition of the American Federation of Teachers’ monthly magazine leads with an article about creating confident readers. The author, a retired teacher turned corporate rep, scolds readers for not following the science of reading. She them moves to the sales pitch, putting her reading development program out there as the “rocket science” of professional development offerings.

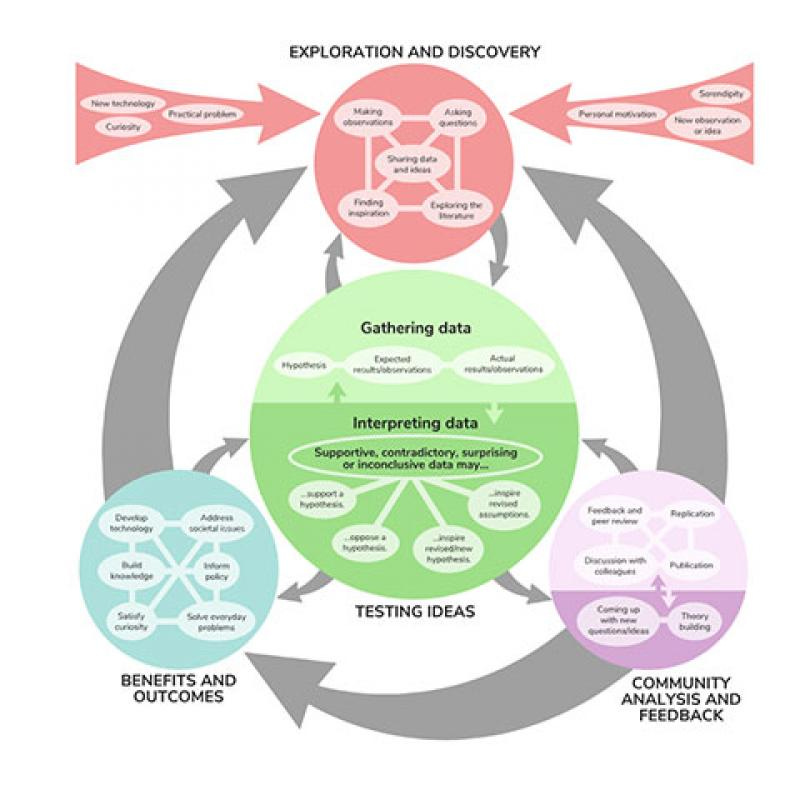

If you’ve been reading my content for a while, you’ll know where I’m about to go with this. In the sciences, inquiry generally begins with discovery and exploration. Data is gathered and interpreted. Assumptions are tested and refined. Contradictory information is explored. Feedback is received and processed. All of this activity seeks to refine the expected outcome of the inquiry.

The so-called science of reading doesn’t seem to follow this pattern. It starts with Natural Language Acquisition, then throws out one of the two types of human language acquisition to focus exclusively on Analytic Language Processors (ALP). For Gestalt Language Processors (GLP), we’re assigned the “disordered” label and ignored in the general education classroom. Those with the privilege of place or wealth may get an IEP that addresses their “deficits.” Others, like me in my youth, are simply promoted through graduation … remaining largely illiterate.

Considering that GLP has been known and studied since at least the early 1980’s, there’s no excuse for the current paradigm.

So, considering the “rocket science” AFT article, and the author’s program, if it was science that was being used in the development of this program, they would have noticed that it didn’t work for about 40% of the studied population … regardless of gender, age, race, or place. That datapoint alone should have caused them pause. But, it didn’t. This many years later, they’re now getting serious about reading … and not in a good way.

It’s all the teachers’ fault

From the standpoint of an autistic GLP who graduated from a decent public school system functionally illiterate, I’d like to examine the author’s premise and proposals.

Nice pull quote. I’m all in. But, sadly, each child should be re-written as “each ALP child.” Equity in this plan doesn’t extend to GLPs. I’ve written elsewhere about how I’ve rarely seen myself in books and lessons, even now as a credentialled teacher.

Nevertheless, this teacher wants to put this “rocket science” on the teachers, and hold them accountable for the results. Imagine that. Giving them a program that, if implemented and if it works as stated, will bring some benefit to about 60% of the student population. What happens if they lift those 60% whilst leaving the 40% behind? In the classic grading model, 60% is a low “D.” Would the system consider a low “D” success? Would that grade cause them to check their assumptions? I doubt it.

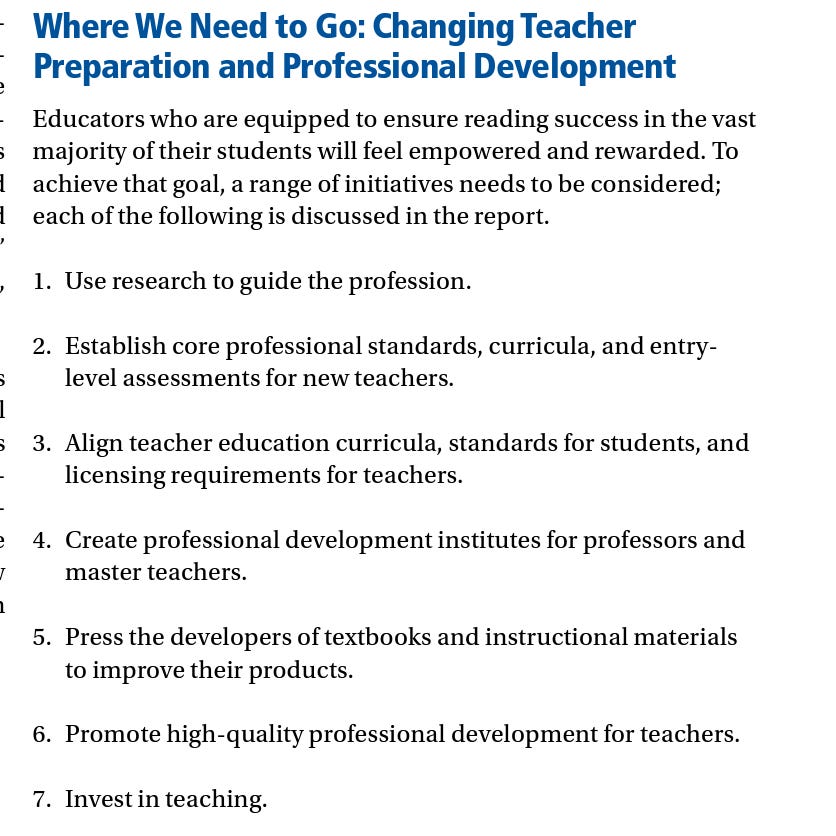

Here’s part of the author’s proposal.

Knowing the basics of reading psychology and development sounds great until you realize that she’s not talking about Natural Language Development (acquisition). Learners in her program will learn “the science of reading,” which willfully ignores GLPs. Learners will not even learn that GLPs exist. Thus, they’ll be frustrated in their classrooms as they wonder why about 40% of their students aren’t responding.

Understanding language structure is a great goal. But the language under study makes a big difference. If it’s science, then it would work regardless of language. But, as I’ve noted recently, there are some languages that are easier than others to acquire / learn in GLPs.

Applying best practices is a nice sounding phrase, but it means absolutely nothing if the data is informing you that you’re missing a sizable minority of your students … and you don’t know why.

It gets worse for teachers as they get further into the document.

I don’t think that I need to beat up the author further. All of these seven points will be informed by the “science of reading” and her “rocket science” program. This is just a call for legislation that will enshrine her POV into funding. This is how western capitalism works. The goal is to get a recurring line item in budgets. What she’s asking for in this proposal stands to secure hundreds of millions of dollars for her employer / publisher. This, and it doesn’t work as advertised.

So what does work?

I teach an English development class consisting of 9-12 graders. All test below the 6th grade level on reading comprehension and writing on the usual standardized tests. But, all are quite bright and very creative. The majority have an IEP eligibility of Specific Learning Disability, a few have an eligibility of Other Health Impairment, and one is autistic. Most have accommodations of chunking information, providing sentence starters for writing assignments, and more time given to complete assignments

From our curriculum, they were given the following writing prompt at the beginning of class: who is braver, a person who leads a group of people, or someone who decides not to follow along with the behavior of the group? Answer the question in the form of a full-length essay. Be sure to support your response with evidence from stories, movies, real world events, or experiences from your life.

After each stared blankly at the page for about five minutes, I changed things up for them.

First, we pulled out the essential words and placed them in a four-box grid. We chose the words “brave,” “leader,” “behavior,” and “group.” Each word occupied a square.

Next, I asked them to make a quick sketch for each word in its square. In the theatre of their mind, they would envision a scene around the words and make a quick drawing that best captures their ideas around that word. The drawings didn’t have to be beautiful or accurate, but they did have to be meaningful to them.

Here’s an example from the class.

Having completed the sketches, I asked them to turn to their elbow partner and describe in their own words what was happening in each box. The parters would discuss the scene, ask questions, and help each other clarify what was happening in each of the frames. This took about 10 minutes.

Once they were able to talk it out with their partners, they had the necessary language scripts in their working memory. They were able to connect these scripts, these gestalts, to the main words in the prompt. I then asked them to write down what they had shared for each of the four boxes.

Here’s what that looked like, from the same student.

I let them know that this was a rough draft of their discussion session. This was by no means a final draft of their response to the prompt. Each of the students was able to produce 2-5 sentences per box.

With these notes collected, the students had created their own sentence and paragraph starters. They had supported their own learning. They all had experience with these words. They just needed an alternative way of accessing what was already in their heads. Creating these sketches from their mental images was a key to unlocking the words, the discussions necessary to complete the assignment.

A different way of proceeding

Using the typical graphic organizers hadn’t worked with these students. They lacked the connections to know what to put where. Most graphic organizers are designed with ALPs in mind, who will know what goes in which place. GLPs, who lack the scripts for the exercise, need to build the necessary gestalts. Once they do, they’re perfectly capable of responding to the prompt. They just need to be shown the way.

In the end, the students were able to access grade-level content and produce grade level essays. But, more than that, they were given a method for supporting themselves. This method meets them where they are, as they are, and not where the system is and as it wishes them to be.

Would others like to use this process? I’m sure they would. But first, they have to know that there are different types of language processors in their classrooms. Once this is recognized, then the differentiation becomes meaningful. Remember, a big part of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and differentiation is knowing your students. Can you really say that you are engaging in UDL if you don’t know something as fundamental as how your students actually process language?

Recognizing a problem

I give the example of my high school students to illustrate a point, a huge problem in the “science of reading” discussion. Most programs and interventions focus on the elementary grades. What do they have to say about the secondary grades? Not much. High schoolers don’t want to drill phonics. I’m trained in the Orton Gillingham methodology. I know high schoolers don’t want to do those exercises. They’re not “age appropriate.” I need a way to accomplish their literacy goals that acknowledges who and where they are.

I was observing a colleague teach an upper-level English class last year. A student, sitting quietly not reading their assigned book during silent reading time was asked by my colleague, “why aren’t you reading?” The student responded, “it’s boring, Mr.” His response let me know instantly that the student was a GLP. My colleague countered, “it’s only boring because you’re boring. The reader gets about 30% of the enjoyment and information from the text itself. The rest comes from the reader’s imagination. Thus, if you find the reading boring, it must be that you are boring.” As harsh as the response from the teacher was, he had discovered the root of the problem. In this student, there was no connection between the reading and the student’s internal scripts. The student didn’t know how to make those connections and the teacher didn’t help them to do so.

Does the “science of reading” help in such cases? No.

For the past five decades? If these methods have been proven out, why aren’t they working every time that they are tried? Did the National Reading Panel or the National Early Literacy Panel not ask these questions?

How effective are these well-established instructional strategies and recommendations if the data is trending down? Is it the teachers fault? Is it the students fault? Or, is it that there are missing variables in this “science of reading.”

The author places the blame on teachers colleges and classroom teachers. It’s not that the “science of reading” is off-base. No. It’s that it’s not being done correctly, or at all.

You can place me in the latter category. I have a philosophical opposition to their “theories and practices” precisely because they ARE “grounded in evidence” … evidence that it doesn’t work in every case. It may work for ALPs, but it doesn’t for GLPs. And … because of this … I’d rather not see 40% of students carted off to special services when all it takes is to design learning with the actual student in mind. This “philosophy” is called UDL.

The bigger problem

I’ve written a longer more “journal appropriate” version of this article. I’ve shopped it around. It’s been rejected at each publication. Why, I’m never quite told. But, do journal articles that challenge decades of orthodoxy get published in the mainstream publications? No, they don’t. Do journal articles that challenge decades of orthodoxy influence teachers to alter their practice? No, they don’t.

With this in mind, I’ve decided to do to English instruction what I did to autism instruction - I’m writing another book. The big problem, as I see it, is that all of this orthodoxy is presented and enshrined at the teacher prep colleges. Armed with this training, they have no valid framework to examine the data when it arrives in their classroom. Why is about 40% of their class behind the curve? Why does such a large group of student not get it? Something must be wrong with the student, they surmise.

The book, titled Holistic Language Instruction, is framed and founded in lived experience as well as decades of research on GLPs and how we learn. I place Gestalt Language Processing in it’s proper context - as coequal with the majority … a difference, not a deficit … then proceed to offer actual evidence-based methods to teach both types of learners in the same classroom, and across the lifespan. It will be out in 2024 from Lived Places Publishing.