A reckoning with heritage, identity, and empire—why I do not celebrate Tartan Day, and what it means to honour our ancient kinships without forgetting the genocide that made survival necessary.

Introduction

I’m writing this on Tartan Day in the United States. But I won’t be publishing it today. There’s no need to ruin the mood.

Today is a day for parades and pipers, for tartans pulled from wardrobes or ancestry websites, for staged brogue and dram-soaked sentimentality. In cities across the country, the children of the diaspora gather to celebrate what they think is their heritage. But what they’re celebrating—what they’re allowed to celebrate—is a sanitised version of survival. A myth draped in plaid, stripped of grief. A story that begins at the point of departure, with no accounting for what drove us from the land in the first place.

I’ve seen the statue at Helmsdale (above)—The Emigrants. A strong man, bare-chested and barefoot, staring forward with resolve. A child beside him, clutching his arm. It's supposed to look heroic, I suppose. Noble. Stoic in the face of a hard journey. But that statue doesn’t speak of the eviction that forced them out, or the ships crowded with the unwanted poor, or the lands that burned behind them. It doesn’t tell you they weren’t meant to survive. That they were cleared like brush from the glens so the lairds could graze sheep and extract more rent. It doesn't tell you that many of them didn't make it.

There’s a painful irony in building a monument to people whose erasure was policy, not tragedy. And there’s another layer to that irony when, in America, we raise a toast each April to “Scottish pride” without ever naming the genocidal violence that carved the diaspora in the first place. Tartan Day doesn’t honour the displaced. It forgets them loudly. It replaces them with bagpipe nostalgia and Highland cosplay, with no mention of the landlords, the clearances, or the colonising logic that decided we were no longer economically viable.

So here’s my dilemma. I’m a descendant of those cleared Gaels, to be sure—but not all of my ancestors were forced out. Some held on around Clydeside, pushed to the edges of a world that no longer wanted them. My great-grandfather was deported to Canada for his role in the Red Clydeside movement, a working-class uprising that dared to imagine justice beyond imperial order. His story makes clear what the statue at Helmsdale obscures: that “emigration” was not a singular event, but an ongoing process. The so-called Clearances weren’t a moment in time—they were the beginning of a system that punished the poor, criminalised dissent, and exported anyone who didn’t comply. What I inherited isn’t just displacement—it’s the long echo of resistance, and the state’s determination to silence it.

I know the names of the places my ancestors were forced from. I know the taste of bitterness passed down through the generations. I know what it’s like to be told to feel pride while being denied truth. We didn’t so much celebrate as we remembered—Cuimhnich air na daoine às an tàinig thu. My Scottish Marxist grandmother ensured that. I was raised to honour where I came from, but the deeper I looked, the more I saw that what I was meant to take pride in was my ancestors’ removal, reframed as resilience. I was supposed to be grateful we made it. Not angry about why we had to. So how can I celebrate, when what’s being celebrated is the sanitised aftermath of a slow and deliberate unmaking?

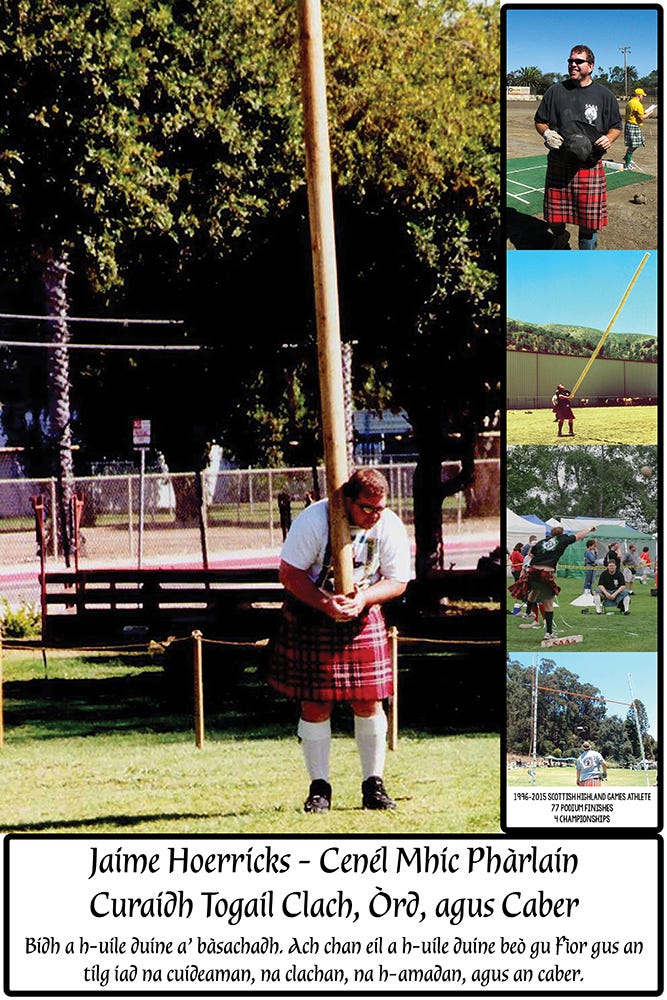

The Disappeared and the Decorated: My Time in the Highland Games

Long before my autism diagnosis, long before I came out, I was a champion caber tosser. Over two metres tall and a wee bit more than 29 stone, I was what happens when Highland genes meet American caloric prosperity. I was built for the field—at least on the outside. Inside, I was a storm. I didn’t yet have words for dysphoria, but I felt it in every mirror, every photograph, every clumsy interaction where my powerfully strong body was praised whilst my self remained unspoken. The rage that powered my throws came from deeper than muscle. It came from the weight of being misread by the world and having no vocabulary to name why.

I competed partly out of obligation, partly for the networking opportunities neurotypicals insisted were important, and partly because my employer was there. In that world, I was his prized bull—a show of strength, of masculinity, of cultural continuity. I was expected to perform, and I did. I travelled across the Western U.S., lifting stones, tossing hammers, and heaving weights for height and distance. The weights had their origins in battlefield artillery—iron reminders of violence. The stones and hammers were echoes of the blacksmith’s forge, the back row of the village where strength and survival were shaped together. These tools had martial history etched into their very design, and I was expected to animate them.

And so I did—weekend after weekend, in sweltering sun or mountain chill, in front of thousands who’d paid a princely sum to watch the show. Pipe bands marched. Tartans flapped. Banners were hoisted. And I entered the ring, a living monument to an imagined past. I knew my role. I knew what I symbolised. I also knew it wasn’t really me they were applauding.

There was pride in the precision of the throw, the rhythm of the run-up, the clean turn of the caber—but there was no peace. The arenas were loud, chaotic, and overwhelming—auditory overload, unpredictable social dynamics, strangers pressing too close. At the time, I didn’t know the word autism, but I knew what it felt like to crash hard after a day of performing strength in an environment that shredded my nervous system. I knew the deep fatigue that followed a successful weekend, the hollowed-out quiet on the long drives home, the sense of being both celebrated and emptied out. No one ever asked if I enjoyed it. Enjoyment was beside the point.

The Highland Games honour strength and resilience, yes—but they rarely ask why those qualities were needed in the first place. They don’t speak of the Clearances, of forced removal, of cultural obliteration. They celebrate what remains without acknowledging what was destroyed. I was upholding a memory I wasn’t allowed to fully understand. I could lift its weight, but not question it. I could embody a past that excluded me, even as I gave my body to it.

It is hard to explain the ache of being both central and invisible—of being the show, but never the self. The part of me that was queer, trans, autistic—that part had no place in the arena. It was strength they wanted. The rest was a liability. So I tucked it away, out of sight, and carried the weight for as long as I could.

“Good Economics” and the Gaelic Genocide

Professor Jason Hickel speaks often of “good economics”—not as something benevolent, but as the cold, euphemistic language used by empire to justify human suffering. Under this logic, entire populations become inconvenient, entire cultures inefficient. Starvation becomes an unfortunate side effect of progress. Displacement becomes mobility. Poverty becomes a necessary discipline to keep wages low. The metrics are clean. The human cost is externalised. It’s all very rational.

This logic is not new. The so-called Highland Clearances—the genocide of Na Gàidheil—were an early, brutal expression of it. One of the first times modern capitalism ran its calculations on a native European population and decided they were no longer viable. But what was destroyed was more than a population—it was a lifeway. The Gàidhealtachd was not merely a place to be lived in; it was part of the people, and they part of it. The land was not property. It was kin. Ancestors were buried in its soil. Stories were etched into its hills and glens. Generations had lived with the land, not on it, not above it—part of a cycle of mutual sustenance, belonging, and care.

But the new logic did not see that. The lairds who sold out their own people—their cinnidhean, their kin-groups—weren’t viewed as traitors by the system. They were hailed as innovators. They were rational actors responding to the market. Land was no longer judged by its capacity to nourish life or memory, but by how much rent it could yield. Communal ties, ancestral belonging, language, kinship—these were deemed inefficient. Obstructive. Economically backward. Sheep, after all, didn’t require schools, doctors, or resistance.

It was progress, they said. Improvement. Modernisation. The same vocabulary now used to sell austerity, forced privatisation, and land grabs across the Global South was trialled first in the glens and straths of Alba. The Gaels were the test case—cleared from their homelands and labelled surplus, then exported to the colonies to help clear others in turn. Some became settlers. Many became indentured. Most were just trying to survive. Their suffering was never recorded as a cost. It was simply factored into the profit margin.

When I read Professor Hickel’s work, I feel the edges of something I’ve long carried but never had the academic language to frame: that what happened to my ancestors wasn’t some tragic inevitability—it was policy. A deliberate restructuring. A calculated outcome of a system learning to turn people into surplus and land into rent. It was happening even as Adam Smith was penning The Wealth of Nations just across the Lowland hills. He watched the rise of capitalism from Kirkcaldy, whilst Highland communities were being torn apart not far to the north. And if he noticed, he did not flinch. The suffering of Na Gàidheil did not trouble the Enlightenment’s tidy equations. We were not the subjects of rational inquiry—we were its necessary collateral.

What was done to us was not a misstep. It was a prototype. The blueprint for what would follow across continents. And the reason it is not remembered as genocide is devastatingly simple: it worked. The people were cleared. The land was capitalised. The story was rewritten.

So when is genocide not recognised? When it’s profitable. When the targeted are first rendered a problem to be solved. When language, kinship, and belonging are reclassified as inefficiencies. When the ledger balances cleanly enough to silence the grief.

Empire’s Selective Memory: Who Gets to Matter?

Empire does not remember evenly. It remembers what flatters, what justifies, what sells. The rest is buried, reframed, or omitted entirely. In a piece I wrote in 2023, I asked: When is genocide not genocide? The answer remains the same—when empire is the perpetrator. When the crime serves its interests. When acknowledging the full scope of harm would disrupt the story it tells about itself.

Tartan Day is one of those stories. It asks us to honour survival whilst forbidding us to speak of what we survived. It aestheticises what remains and demands gratitude for the scraps. The tartan is welcome, the trauma is not. The pipes are celebrated, but the silence that followed the Clearances—the silencing of language, of memory, of belonging—is erased. We are meant to remember the music, but not the mourning. The exile, but not the eviction. The strength, but not the stripping of self.

And always, always, the same flattening: Scots were colonisers too. As if that erases what was done to Na Gàidheil. As if all Albanach were equal participants in empire, rather than its early victims and, later, its coerced instruments. What this myth omits—deliberately—is that most Highland emigrants did not arrive in the colonies as lords of anything. They came in steerage. As indentured labour. As political dissidents. As people made surplus by the new economic order. Many had no choice. They were not settler-colonisers in the imperial sense—they were fuel.

The English had a particular sentiment about the Highlander: They like to fight, and they’re good at it. So they put that to use. What had once been resistance was rebranded as reliability. What had been rage became discipline—so long as it could be channelled in the service of the Crown.

The Black Watch—Am Freiceadan Dubh—was among the first. Raised officially in 1739 from Highland clans considered “loyal,” their job was to police their own. They patrolled the Highlands in the wake of the Jacobite uprisings, not as liberators, but as watchmen—internal enforcers tasked with pacifying a culture they themselves belonged to. Their dark tartan gave them their name. Their legacy would stretch across continents—from India to Africa to the trenches of France. They were remembered for their bravery. Less often for the work they did enforcing imperial will.

My own great-great uncle served in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders during the Great War—fighting for a Crown that had already torn through our people’s language, land, and lifeways. As he fought in Europe, his brother—my great-great grandfather—worked the yards on Clydeside, only to be “deported” during Red Clydeside for daring to organise against the same economic system that had emptied the glens two generations before. One wore a uniform. The other wore chains.

This was not an uncommon path. The British state was skilled at transforming the rebellious into instruments of its own stability. In both Alba and Éire, the playbook was the same: criminalise political resistance, especially among the poor and the radical. Then offer clemency through service—join the Army or the RUC, and maybe you’ll avoid prison. Maybe you’ll feed your family. Maybe you’ll survive.

Highland Scots, like their Irish counterparts, were coerced into military or police service not out of loyalty, but necessity. Some were sentenced for acts of resistance and offered the uniform as a lesser punishment. Others joined because hunger left no other option. Either way, the result was the same: empire repurposing its most dangerous threats—those with fire in their bellies and memory in their bones—into tools of enforcement. The imperial strategy was devastating in its simplicity: divide, break, enlist. Turn would-be revolutionaries into state agents. Send them back into the communities they might once have fought to defend.

The result is a tragedy wrapped in uniform and ceremony. Those conscripted into the British Army or RUC often found themselves enforcing the very order that had shattered their own lives—or deployed against people with whom they shared cultural and political bonds. They were told it was a choice. But there is no real choice between prison and enlistment, between starvation and a paycheque, between exile and a gun.

That is not complicity. That is conscription. That is what empire does—it turns the dispossessed into its front line. It repurposes pain into policy, rage into order. It criminalises resistance, then offers the uniform as clemency. It doesn’t offer choices. It offers conditions. And then it writes the history to make it look like consent.

This is the myth of freedom under empire: that we chose to serve. That we were proud to do so. But survival is not allegiance. And service under duress is not endorsement. Still, the empire wraps it all in ceremony and tartan, rebrands coercion as honour, and calls it heritage.

So when I see the parades and plaid, the cheerful re-enactments, the simplified stories of “Scottish contribution” to the New World, I cannot help but ask: Whose story is this? Because it is not mine. And it is not my ancestors’. We were not the architects of empire. We were what it built itself on.

Survival Is Not Consent

I carry the blood of Cenél Mhic Phàrlain, the kinship of MacFarlane. Not the tidy tartan stall version of a clan, but the fractured line of a people known for their night raids, their fierce independence, and their stubborn refusal to vanish. Clann Phàrlain nan Creach—MacFarlanes of the Raids. We were border dwellers, mountain folk, guardians of Highland passes and children of shadow. Our tartan runs dark—deep blue like the lochs, green like the ancient woods, black like mourning. Crimson threads wind through it, thin as bloodlines, thick as memory. The motto is “This I’ll defend.” And perhaps that, too, is what remains in me: not the sword, but the refusal. The bone-deep instinct to say no more.

But even within the legacy I was born to, I was never fully welcome. I am neurodivergent. I am trans. I am working-class. I was raised in a world that celebrated tartan but would not acknowledge the body I live in, the truth I carry, the shape of my mind. The same culture that asks me to lift stones in the name of tradition would flinch if I spoke plainly about who I am. It made room for the parts of me it could use—my strength, my silence, my willingness to perform. But not for the fullness of me. That had to be left out of frame.

The irony stings. I wore the tartan. I competed under the banner of kinship. I played my part in the theatre of heritage. And yet the very things that made me me were always just slightly out of bounds. We celebrate survival, but only in forms palatable to the settler gaze—forms that keep queerness invisible, neurodivergence unspoken, and working-class grief aestheticised as grit. I showed up with my body, but was asked to leave everything else at the gate.

But survival is not consent. Participation is not permission. I did not agree to the terms of my inclusion. I simply endured them. The tartan fly plaid on my shoulders wasn’t pride—it was weight. It was remembrance. It was grief wrapped in ceremony. I showed up not because I was welcomed, but because I refused to be erased. I had no words yet for the kind of defiance that takes the shape of presence, but I was already living it.

And so I honour my ancestors, but not through parades or performances. I honour the kinship that survived fragmentation. I wear the MacFarlane tartan not as costume, but as ritual. As memory. Not the Anglicised Clan MacFarlane, but Cenél Mhic Phàrlain—a living line of people made separate by empire, robbed of name and voice, and still here. My younger sister has traced our line—the Allans—back to the 1600s. The records tell part of the story. The rest is carried in the body. We are a separated family, but not a lost one.

This I’ll defend—not with bravado, but with clarity. With grief. With breath. I am still here. We are still here. And we remember.

Final Thoughts …

I don’t celebrate Tartan Day.

I don’t wear the tartan as costume. I don’t toast the myth of rugged perseverance that asks me to honour survival but forget the reasons survival was necessary in the first place. I don’t celebrate a performance of heritage that erases the pain, silences the politics, and sanitises the blood.

Because what happened to my ancestors was not a backdrop. It was not a dramatic interlude on the way to something nobler. It was genocide. It was economic restructuring by another name. It was land theft, culture stripping, and forced removal—written in ledgers, justified by theory, and carried out in fire and law.

Tartan Day could be something else. It could be a day of reckoning. Of truth-telling. Of facing the full weight of what was done—and what continues to be done in similar form across the globe. It could hold the memory of Highland women who watched their homes burn, of men jailed for organising on Clydeside, of children shipped across oceans with no names and no return address. It could name the silences we carry. But it does not.

So I do not celebrate my people’s genocide.

My tartan is not for sale. It is not heritage for hire. It is memory. Blood. Language. Silence. Grief. It is the cry of names nearly forgotten. It is the story that survives in fragments, in muscle memory, in the long pause before answering where we’re from. I do not wear it to belong. I wear it to remember.

And I honour it by speaking plainly, especially when it’s uncomfortable. Especially when I am asked to smile. Especially when the music swells and the past is repackaged as pride.

Because if I must carry this history, I will carry it truthfully.