This is Not the Final Version: Autistic Time, Transition, and the Fluidity of History

An Autistic Perspective on History, Time, Memory, and the Endless Process of Becoming

What if history were told through autistic time? Today’s article explores autistic temporality, transition as return, and the recursive nature of thought—challenging the neuro-majority’s models of time, identity, and understanding.

Introduction

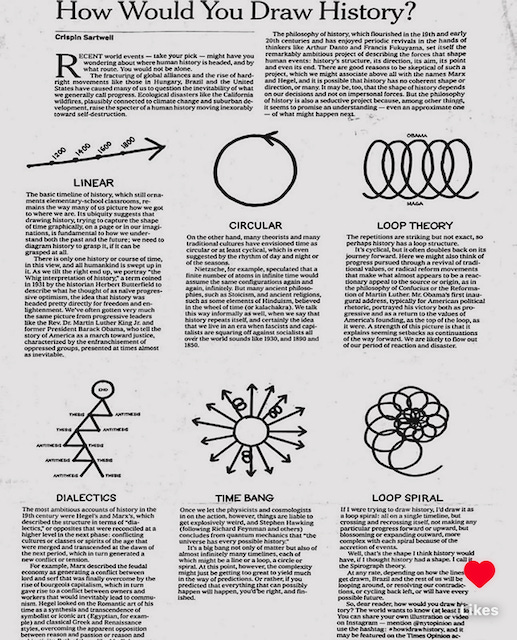

A message popped up on my phone—an Instagram DM from a friend. Just a link and the image below, no commentary, to a New York Times article titled “How Would You Draw History?” I tapped, and there it was: the story and graphic attempting to map the ways people conceptualise time. The usual suspects appeared—linear, cyclical, dialectical. The idea was to represent history visually, offering frameworks for how we move through time. It was interesting, but almost immediately, I felt something was missing. Not in a vague, abstract way, but in the way that triggers an immediate, near-physical sense of incompletion—a space where an entire branch of experience should be but isn’t.

That feeling set off a cascade, the kind that happens when a single spark of thought rushes through the neural pathways, drawing up connections at a speed that feels near-instantaneous. The image, the framing, the conversation it presumed—within moments, my mind had pulled in seemingly unrelated pieces: an old article I wrote about retrocausality and the rewriting of experience, my book’s discussion of Glasser’s Choice Theory and autistic temporality, the way my own transition had never felt like a shift in identity but rather a return, a final coherence between internal reality and external form. It wasn’t just a reaction to the article; it was an entire restructuring of thought in real time, a reordering of ideas into something that had always been there but had just found its focal point.

Tracing the Thought Cascade

The graphic in The New York Times article laid out familiar ways of conceptualising history: linear, cyclical, dialectical. Each had its own logic. The linear model follows a straight path—progress unfolding over time, the dominant Western view that assumes history is always moving forward, even if reality suggests otherwise. The cyclical model sees history as repetition, the rise and fall of civilisations in a looping inevitability. The dialectical model, drawing from Hegel and Marx, envisions history as driven by conflict—each moment of contradiction resolving into a synthesis, which then becomes the new thesis to be challenged in an endless progression. Each of these frameworks attempts to impose structure on time, but none capture the autistic experience of temporality.

As I sat with the image, my brain pulled in connections at a speed that felt near-instantaneous, as if the missing piece in the diagram was already there, just waiting to be slotted into place. The thought leapt first to my old article on retrocausality—how my gestalts, the way I process and store experiences, rewrote themselves almost immediately after I came out. My past didn’t just stay fixed; it reconfigured itself to reflect my new understanding of self. From there, it jumped to my book, where I’d written about Glasser’s Choice Theory and its emphasis on internal motivation—how the autistic brain doesn’t experience time as a strict sequence but as something teleological, goal-driven, shaped by coherence rather than external chronology. Then, of course, to my own transition—not a transformation but a return, a reconciling of external reality with the truth that had always existed in my mind.

This wasn’t just an intellectual exercise. It was a textbook example of autistic cognition in action—not a linear train of thought, but a rapid-fire, gestalt-driven process, pulling together memories, theories, and experiences into a single, integrated understanding. It was also a reminder that our concept of time is fundamentally different. We don’t just recall events. We rewrite them. The past isn’t a fixed point on a line—it reshapes itself as we integrate new information, meaning the self is always fluid, always updating, always finding ways to make sense of what was in light of what is.

And then, there was the missing piece from the NYT graphic: flow states. I’d written about them before—how, for autistic people, flow isn’t just an optimal experience but a default way of being. When engaged, time itself ceases to exist in a meaningful way. There is no past or future, only the deep now. This aligns perfectly with the way my gestalts update—because if time isn’t an external force but an internal construct, then of course it changes as our understanding does. The neurotypical models of time in the article all assume an external framework—time moving forward, repeating, or evolving through struggle. But for us, time is something else entirely. It is internal. It is fluid. It exists only in relation to engagement, meaning, and coherence.

It was clear to me now: what was missing from the NYT’s attempt to map history was a model that accounted for autistic temporality—one where history isn’t something we move through, but something that continuously reconstructs itself in response to who we are becoming.

The Missing Model: An Autistic View of Time & History

None of the models in The New York Times article truly fit how I experience time. Linear, cyclical, dialectical—each assumes an external framework, an objective structure that exists independently of perception. But for me, time has never felt like a force that marches forward, repeats in loops, or progresses through conflict. Instead, time has always been something teleological—not a fixed sequence, but something that exists in relation to meaning and coherence. The question is not when something happens, but why it matters, how it fits into the ever-evolving structure of my internal world.

This is why history, as it’s typically taught, has always felt strange to me. The expectation is that we move through time the way we move through space, as if events remain static in the past, accessible only through memory. But my experience is different. I don’t just remember the past—I reconfigure it. My mind is not a storage archive of fixed moments but a self-reconfiguring theatre, where past, present, and future shift dynamically depending on new insights, new understandings, new gestalts. A change in self-perception doesn’t just alter my future—it retroactively rewrites my history. My coming out was not a singular event, a step forward on a linear timeline, but a reordering of my entire narrative. The past adjusted itself to make sense of the present. This is not something I actively choose to do; it happens automatically, seamlessly, like a script being rewritten mid-performance to better reflect the story that was always meant to be told.

This is why interruptions are so jarring. When I’m fully engaged in something—a deep writing session, a research dive, a hyper-focused project—time itself disappears. There is no past, no future, only the deep now. This is the natural state of the autistic mind in flow. But when something pulls me out of that state—a loud noise, a sudden demand, an unexpected transition—it isn’t just a momentary distraction. It’s a temporal rupture. The coherence of the moment shatters. The mental theatre, which had been running smoothly, collapses, and suddenly I am forced back into neurotypical time, where everything is external, fragmented, disconnected from meaning. This is why transitions feel so violent. It’s not just about switching tasks; it’s about being ripped out of an internally consistent reality into one that feels alien, unnatural, imposed.

So when I look at the NYT’s graphic, I see an absence—a missing model, a perspective left out. Where is the representation of time as something internal, something dynamic, something governed by coherence rather than chronology? Where is the acknowledgement that for some of us, time is not a path or a cycle but a story we are continuously rewriting?

My Transition as an Example of Autistic Temporality

Neurotypical narratives of transition insist on before and after—as if transition is a break, a crossing, a singular transformation. There is always an expectation of the past self and the future self, a dividing line that marks what came before as something left behind, something altered beyond recognition. But I have never experienced it that way. I did not transform. I did not become. I have always been.

From the outside, it might seem like a shift, but from within, my transition was a return—not a leap forward on a timeline but a moment of recognition, of alignment. The way it unfolded did not feel like progress, or even change, but rather a natural resolution to something that had always been true. My Quality World Picture already contained this reality. It was simply waiting for the external world to catch up.

This is why autistic temporality makes more sense to me than the rigid, linear frameworks imposed by neurotypical understandings of transition. Time is not a force pushing forward; it is a function of coherence. In the same way that my gestalts rewrote themselves the moment I came out, my history reshaped itself to match my reality. It wasn’t that the past ceased to exist—it was that it finally made sense. Events and experiences that had once seemed distant or disconnected suddenly slotted into place, their meaning clarified in ways that had always felt just out of reach.

This experience of time—fluid, recursive, teleological—is something that colonial gender structures were designed to erase. The imposition of gender as a fixed, binary system was not just about power; it was about freezing identity, denying its ability to shift and evolve as part of the natural rhythm of life. Before this imposition, many societies understood personhood not as something set at birth but as something lived, experienced, shaped through relationships and roles. Gender, as it is currently constructed, demands that we exist within static categories, that we explain and prove our right to shift between them. But transition is not a deviation. It is a return to the way things were meant to be—a restoration of what colonial time has tried to sever.

And yet, we are made to justify, to plead our case, to submit to endless bureaucratic processes that demand we account for every step of our own becoming. This is what the first child of the next world cannot understand—why we must fight for something that should never have been taken from us in the first place. Why we were made to choose, when the choice was always supposed to be ours. In their world, there is no “before and after,” no struggle to reclaim what was stolen. There is only movement, transformation, a natural unfolding. In their world, I would never have had to fight for this.

But I was not born in that world. I was born into the fractured present, where time is weaponised against us, where transition is made into a bureaucratic ordeal, where gender is something that must be proved before it can be lived. And yet, the existence of the past before gender, and the future beyond it, tells me that this world is not inevitable. If gender was imposed, it can be undone. If time was stolen from us, it can be reclaimed.

My transition was not a step forward into something new. It was the point at which the internal and external finally aligned. A correction. A return. A refusal to submit to the lie that I was ever anything else.

Why This Matters: Rethinking Time & History Through an Autistic Lens

The models in The New York Times article, and more broadly in mainstream discourse, miss the autistic experience entirely. They assume that history—and time itself—must follow the logic of the neuro-majority, that it moves in ways that are linear, cyclical, or dialectical. But autistic time does not work that way. For us, time is not something that happens to us; it is something that exists in relation to meaning, engagement, and coherence.

And yet, our way of being is constantly framed by the dominant culture as defective, disordered, deficient. When neurotypical parents and teachers of autistic children try to understand us, they do so from the outside, from a perspective that views difference as dysfunction. They rarely seek to understand from within, to see how our cognition functions on its own terms—not broken, but different. For us, we are not disabled within ourselves. It is the world built by the neuro-majority—the world of patriarchy, white supremacy, capitalist alienation—that is foreign, unnatural, unlivable.

This is why I frame myself as a foreigner in this space. This world was not built for me. It demands that I explain, justify, perform my own existence in ways that feel as unnatural as translating poetry into a language that lacks half the necessary words. I am an expat from Værensland, the land of being, trapped in a world that functions on the logic of having. The neuro-majority’s world is one of ownership, categorisation, bureaucracy, surveillance. It insists that we define ourselves through rigid boxes—gender, productivity, compliance—whilst our own existence, our way of thinking, is inherently fluid, patterned around gestalt, meaning, and the teleology of becoming.

This is why it is critical that autistic people tell our own stories, define our own temporality, assert our own ways of being. When we allow neurotypicals to dictate the framing, we are reduced to something incomplete—a problem to be solved, a pathology to be managed. But if we reclaim the narrative, if we articulate our experience of time, memory, and selfhood on our own terms, we disrupt the entire framework that seeks to contain us.

Understanding time through an autistic lens doesn’t just help autistic people—it challenges the fundamental assumptions of the world we live in. It forces a rethinking of transition, of identity, of history itself. If time is not fixed, if history is not a straight line, if transition is not a break but a return, then what else has been distorted by the logic of the neuro-majority? What else must be reclaimed?

So here’s the question I am left with: What if history were told through autistic time?

What if we rejected the imposed frameworks of linear progress and instead embraced the fluid, recursive, meaning-driven temporality that defines our way of being? What if we reinterpreted history not as a series of fixed events but as something continuously reconstructed, shaped by engagement, by coherence, by the recursive logic of understanding?

To tell history in autistic time would be to acknowledge that time is not something external, imposed upon us, but something deeply internal, shaped by cognition, perception, and relation. It would be to challenge not only how we are seen, but how all people understand their own existence.

And that is why this matters. Because if we allow them to define time, they will define us out of it.

The Solitary Forager’s Time - A Journey in Verse

Before the counting of years, before the naming of things,

when the sky was still new and the rivers moved unclaimed,

we walked—alone, yet never lost.

We were the ones who traced the whisper of the wind,

who followed the path of fox and shadow,

who knew the shape of the land

not in maps, but in memory,

not in dates, but in patterns carved by rain.

Time did not press upon us, did not bind us in its grip.

The sun rose, the moon waxed,

but we were not tethered to its rhythm.

We moved with the seasons of thought,

drifted in the currents of knowing.

They call us solitary,

but the forest spoke our names.

The roots remembered where we had stepped,

the lichen bloomed where we had paused.

We were never alone.

Epochs passed like water over stone.

The great ice came and went,

the land shifted,

the herds thundered, disappeared, returned.

And still, we remained,

not in spite of Nature’s hand, but because of it.

The world had a place for those who walked apart,

who saw beyond the horizon’s edge,

who did not need the measure of another’s step to find their way.

And then came the ones who built walls,

who carved the sky into hours,

who said that time must be kept,

that life must be measured,

that the world must be shaped

into something small enough to hold in their fists.

They named us lost.

They called us broken.

They wrote our difference in the language of disorder.

But we remember.

We remember the deep now,

the silence before speech,

the knowing that does not need words.

We remember the old ways,

the ones that came before history was something counted.

We remember who we are,

who we have always been.

Not relics, not mistakes,

but the ones who walk unseen paths,

the ones who listen when the world has forgotten how,

the ones who survive—

not because we were spared by time,

but because time was never our master to begin with.

Final thoughts …

Even as I finish writing this, I know it isn’t finished. It never will be. Nothing I write ever feels final, only the best approximation of my thoughts at a given moment. A snapshot of something still shifting, still growing, still finding new connections. Understanding is never fixed—it is recursive, evolving, adapting as new insights emerge. My autistic time, my autistic cognition, means that what I write today may not fully align with what I would say tomorrow. And yet, the neuro-majority expects permanence, expects conclusions, expects me to freeze something dynamic into a static, finished form.

I struggle with this when I look at my published books, like No Place for Autism?. The words are there, bound in paper and ink, but they are outdated even as they are printed—not because they are wrong, but because they were never meant to be fixed in time. They were gestalts in progress, and yet, in book form, they are locked into place, unable to shift and reconfigure with my evolving understanding. I find myself wanting to rewrite, expand, correct, refine, knowing that my thinking has moved forward, that my understanding has deepened, that the pieces of the picture have rearranged themselves. But the pages remain frozen.

That is why I take so much joy in this Substack—it was never meant to be static. It is a living repository, a place where thoughts do not need to be cemented into finality. It is a space where I can revisit, refine, restructure—where the gestalts can remain fluid, where the delayed echolalia of my mind can find a home. My writing here is never truly finished, but always in conversation with itself, always growing, always shifting in ways that feel natural to me but overwhelming to those used to neurotypical modes of thinking.

I see it when I send someone a link to one of my longform pieces—a 5,000-word response to a question they expected a simple answer to. To me, it is just a fraction of the whole picture, the best I can do in this moment to explain something vast and layered and deeply interconnected. But to the neuro-majority, it is often too much—too dense, too complex, too overwhelming. They are used to their trivialities and banalities, to conversations that skim the surface of things rather than diving into their depths. They want quick, digestible answers, when my way of knowing demands immersion, recursion, depth.

This is why seeing something like The New York Times article on history stings. Not just because our experience of time was omitted, but because it always is. The world does not expect our depth. It does not make room for the way we process, the way we understand, the way we build knowledge. It does not even acknowledge that our way of existing is equally valid—perhaps even necessary—to fully grasp the complexity of history, time, and self. Instead, it reduces us to footnotes, anomalies, inconvenient deviations from the standard.

And so, I am left with this loneliness—not just personal, but structural, built into the very fabric of a world that does not reflect me. An expat from a foreign space, stranded in a land where nothing makes sense. The way people think, the way they move, the way they simplify everything to fit within pre-approved boundaries—it is as strange to me as a false sky, as a language missing half its vocabulary. I am expected to live within their system, but their system is foreign to me.

Yet, even as I sit with this, I know my work is not to force myself into their frame, but to continue articulating what has always been missing. To write into the absence. To make visible what they refuse to see. To offer not conclusions, not fixed answers, but the best articulation I can manage in this moment—knowing that even this will continue to evolve.

So even as I reach this last sentence, I know it is not truly an ending. Only a pause before the thought continues.