The Verdict Is In: ‘Evidence-Based’ Education Fails the Test of Real Science

How Junk Science in the Classroom Harms Students, Silences Teachers, and Serves Profit Over Proof

As a former forensic scientist, I know real science demands rigour. In education, “evidence-based” has become a slogan, not a standard—used to enforce compliance, not truth. It’s time teachers demand proof, not branding.

Introduction

Before becoming a teacher, I served as a Senior Digital / Multimedia Forensic Scientist with the City of Los Angeles, where my responsibilities included the collection, analysis, and authentication of multimedia evidence—audio, video, and imagery—across thousands of cases. Alongside my primary role, I was “on loan” in a voluntary capacity to the Organisation of Scientific Area Committees (OSAC), where I was a founding member in 2014 and served two full terms, concluding in 2018. During that time, I chaired the Video Task Group of the Video/Imaging Technology Analysis Subcommittee and was part of the Human Factors Task Group, where I worked closely with experts like Dr Roy Haber to develop standards that would safeguard the integrity of forensic science in courtrooms across the country. We were united by a belief that science—real science—must be reliable, repeatable, and reproducible. Anything less risked injustice.

Throughout my forensic career, I was also part of the team that wrote the NIJ’s Interview Room Recording standards, FLETC’s RECVR class on evidence retrieval, and Best Practices for the Retrieval of Video Evidence from Digital CCTV Systems. I authored nearly 2,000 articles on the Forensic Photoshop Blog between 2007 and 2020, and in 2008 wrote the best-selling book Forensic Photoshop. I mention all of this not to brag, but to make it plain: I know what science looks like. I’ve lived and breathed it. I’ve fought to keep junk science out of courtrooms because the stakes were clear—real human lives, real consequences. In forensic science, junk science sends innocent people to prison.

Now, as a teacher, I’m seeing the same degradation happening in education—only now, it’s children being sentenced to interventions that don’t work, and teachers being blamed when they fail. The stakes are no less real, and the misuse of science is no less dangerous. Where once I challenged the misuse of ‘evidence’ in legal settings, I now see the term ‘evidence-based’ being wielded in schools—not to inform, but to compel compliance, to shut down critical thought, and to market products under the guise of research. The veneer of science is being used to enforce decisions that, if subjected to proper scrutiny, would fail to meet even the most basic scientific standards. Having fought this battle once in the justice system, I now find myself fighting it again in education. And once again, it is those with the least power who are paying the price.

The Debasement of ‘Evidence’—From Law to Education

In forensic science, the Daubert standard was developed precisely because bad science had made its way into courtrooms—science that lacked rigour, could not be tested, and could not be reproduced by others. The Daubert standard aimed to put a stop to this, by insisting that any scientific evidence admitted in court be reliable, repeatable, and reproducible. It wasn’t enough for an expert to say something “worked.” They had to prove it could work again, in different hands, under scrutiny, and without the benefit of hindsight or bias. This was the bulwark against false convictions, biased testimony, and the misuse of scientific authority.

But over time, even those standards began to erode under pressure—pressure from backlogs, from political expedience, from institutions more concerned with convictions than with justice. As I wrote in 2019, too often “science” became a matter of who performed the analysis rather than how it was done, with results treated as infallible because of the analyst’s credentials rather than because of sound, tested methodology. When reliability is assumed instead of demonstrated, when results cannot be repeated independently, and when methods cannot be reproduced by those outside a privileged circle, that isn’t science—it’s faith in authority masquerading as evidence.

And this is exactly what I now see happening in education. The term “evidence-based” is deployed constantly, yet rarely with any indication that the underlying research has been subjected to the kind of scrutiny Daubert demands. Teachers are handed interventions, curricula, and training sessions that claim the mantle of science but offer no proof—no proof that the results are reliable across contexts, no proof that they are repeatable by real teachers in real classrooms, and no proof that independent researchers—especially those without ties to the original study or its funders—can reproduce the findings.

Worse, “evidence-based” has become a marketing slogan, not a standard. Interventions are sold not on the strength of their science, but on the strength of their branding, often funded by the very corporations that stand to profit from widespread adoption. Just as bad forensic science served institutional needs over individual rights, bad education science serves institutional convenience over student needs. And the consequences are similarly profound: students subjected to ineffective or harmful interventions, and teachers scapegoated for failing to achieve outcomes that were never scientifically sound to begin with.

In both arenas, the debasement of evidence is not accidental—it is systemic, driven by the same forces of expediency, compliance, and financial interest. Having once fought to uphold scientific integrity in the courts and in committee work, I now find myself alarmed by its absence in education—and by how easily teachers are coerced into compliance under the illusion of “science,” when what they are really being offered is faith-based policy dressed up in the trappings of research.

Dissecting an EdWeek Article—A Smokescreen of Compliance

The EdWeek article, What Teachers Should Know About Education Research, presents itself as a helpful guide for navigating the world of educational research, but it functions more as a smokescreen of compliance, instructing teachers to accept the authority of research without question. It offers no critical lens for evaluating whether that research meets even the basic standards of scientific integrity. There is no mention of reliability, no interrogation of repeatability, and certainly no concern for reproducibility—the very things that separate sound science from marketing material.

Let’s take these in turn. First, reliability. The article encourages teachers to trust “high-quality” studies, but fails to explain how such quality is determined. In reality, many of the studies that drive educational policy are conducted in small, homogeneous settings, often under controlled conditions that bear no resemblance to the complex, dynamic environment of a real classroom. For students who are disabled, multilingual, or otherwise marginalised, these interventions may be entirely inappropriate, having never been tested with populations like theirs. Yet the findings are generalised, and teachers are expected to apply them universally, as though human beings are interchangeable and context is irrelevant. This is unreliable science, and yet it forms the basis for mandates and evaluations that directly impact students’ lives.

Next, repeatability. The article adopts the tired refrain of “fidelity of implementation”, a notion that suggests interventions only fail because teachers are not following the script correctly. In forensic science, when a method fails to yield consistent results, we question the method. In education, we blame the teacher. This is an inversion of scientific reasoning. If something cannot be repeated by a wide range of practitioners, under typical conditions, it has no business being labelled ‘evidence-based’. Yet teachers are burdened with the failure of methods that were never designed for the diversity of real-world classrooms, forced into compliance with approaches they cannot ethically or effectively deploy.

Finally, reproducibility—the cornerstone of science. In my work as a forensic scientist, if a method could not be replicated independently by someone without ties to the original study, it would be inadmissible in court. In education, such methods are not only admissible—they are branded, sold, and imposed, often by those with a financial or ideological stake in their adoption. The education research reproducibility crisis is well-documented, yet the EdWeek article avoids this entirely, preferring instead to encourage passive consumption of research rather than critical engagement with its validity.

As I wrote in 2019, science requires transparency, testability, and scrutiny—not acceptance based on reputation or institutional prestige. By failing to equip teachers with the tools to ask “Is this method reliable? Can I repeat it? Has it been reproduced by independent experts?”, the EdWeek article disempowers teachers and legitimises bad science. In doing so, it aligns with systems of control, not systems of knowledge.

‘Evidence-Based’ is a Marketing Slogan

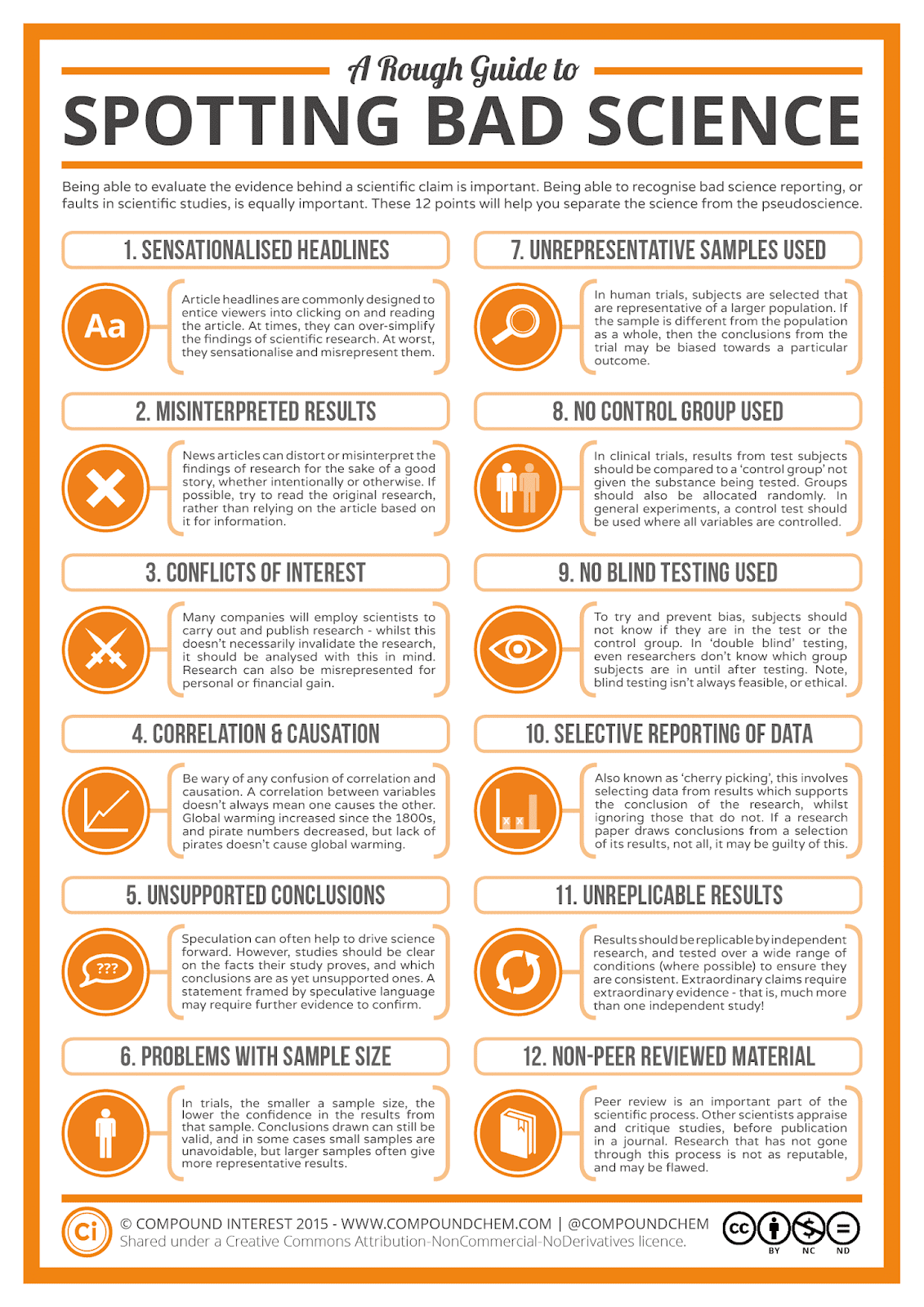

In forensic science, we had a term for flashy methods that made big promises but crumbled under scrutiny: junk science. Often, these methods were accompanied by sensationalised headlines, conflicts of interest, unsupported conclusions, and a conspicuous lack of peer review—all classic hallmarks of what Compound Interest’s Rough Guide to Spotting Bad Science (above) calls pseudoscience. Unfortunately, I now see these same patterns playing out in education, where “evidence-based” has morphed into a marketing slogan, wielded to compel obedience, not to advance understanding.

Take, for example, “autism interventions.” Many of these—particularly Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) and its variants—are labelled “evidence-based,” yet lack replicable results outside of narrow study parameters. As detailed in my breakdown of the Autism Research Centre’s failures, the interventions often cited as “proven” have limited long-term benefit, with outcomes framed by selective reporting of data and research conducted by those with financial ties to service providers. These studies frequently involve small, unrepresentative samples, no blinding, and often no control groups—ticking nearly every box on the bad science checklist. Nevertheless, these methods are pushed onto teachers and parents as mandatory treatments, and resistance is treated as negligence, not critical thinking.

Similarly, the so-called ‘Science of Reading’ has become another weaponised slogan. What began as legitimate research into phonemic awareness has been commandeered by corporate interests to promote scripted curricula and high-priced assessments, with little regard for diverse learners, including neurodivergent and multilingual students. Educators who question the one-size-fits-all approach are accused of being “anti-science,” even though many of the programmes being sold under the ‘Science of Reading’ banner have never undergone independent replication. Once again, marketing trumps methodology.

The issue here is that “evidence-based” implies rigour, neutrality, and trustworthiness, but in practice, it often masks a lack of transparency, peer review, or replicability. In forensic work, this kind of branding would have never passed a Daubert hearing. In education, it passes for policy. The goal isn’t better student outcomes—it’s institutional compliance and financial profit. As I noted in 2019, real science requires constant interrogation and refinement, but in education, dissent is silenced, and teachers are cast as barriers to implementation rather than ethical practitioners with a duty of care.

In both fields, the abuse of science language serves the same purpose: to assert authority, reduce autonomy, and enforce standardisation, often for the benefit of private entities. When we abandon reliability, repeatability, and reproducibility, we are not practicing science—we are participating in a system of control, wrapped in the comforting, but ultimately hollow, language of “evidence.”

Final thoughts …

In the courts, the Daubert and Frye standards were established as safeguards to ensure that only evidence processed using methods proven to be reliable, repeatable, and reproducible could be presented, along with expert testimony based on those methods, to the Trier of Fact—the judge or jury responsible for deciding the case. The aim was to prevent harm—to stop juries and judges from being swayed by expert claims not grounded in real science. And yet, even with these standards in place, the system is far from immune to bad science. In one of the most shocking examples, ProPublica revealed how an FBI forensic scientist’s unfounded expert testimony helped secure convictions by suggesting connections to crimes that his lab results couldn’t prove. This wasn’t just a lapse in rigour—it was a systemic failure of oversight, accountability, and scientific integrity. Real lives were destroyed because science was used as a tool of authority, not a method of inquiry.

This same dynamic is now rampant in education. The term “evidence-based” has become a shield—a way to deflect questions, suppress dissent, and push interventions that often lack any meaningful basis in replicable research. Educators are told to trust the label, not interrogate it. But it’s time to stop accepting these claims at face value. It’s time to ask the same questions any competent courtroom would (or should):

Where’s the study? Who funded it? Was it peer reviewed? What were the limitations? Who benefits? Was it ever reproduced independently? Was the sample representative of the students we actually teach? If the answers to these questions are vague, withheld, or absent altogether, then the intervention is likely not science—it’s policy or profit masquerading as research.

As educators, we must demand real evidence—not to reject research, but to honour the responsibility we hold for our students. In law, when science is misused, people lose their freedom. In education, when science is misused, children are subjected to interventions that fail them, and teachers are blamed for the fallout. The harm is just as real, and just as lasting.

This critique is not about rejecting evidence. It’s about insisting on rigour, ethics, and justice. It’s about resisting the pressure to become passive implementers of branded compliance tools. If a method isn’t reliable, repeatable, and reproducible, it isn’t science—and it has no place in our classrooms. The verdict is in, and it’s time educators stop participating in systems that demand obedience, not truth. Push back. Ask for proof. If it can’t stand up to scrutiny, it doesn’t belong in your practice.