The Stages of Grief: A GLP's Journey Through Standardised Testing in College Coursework

Standardised tests are deeply entrenched in the educational system, often viewed as the definitive measure of a student’s ability and knowledge. These tests are designed to assess students across a broad range of content, presenting a supposedly objective and uniform evaluation. However, for many neurodiverse individuals, particularly autistic Gestalt Language Processors (GLPs) like me, these tests pose unique challenges. As someone who processes information holistically—piecing together patterns and meaning—I often find myself at odds with the rigid, yet seemingly random, structure of standardised testing. The disconnect between how I naturally process information and the expectations placed on me to perform under timed, high-pressure conditions leads to a recurring cycle of emotional strain. In fact, preparing for these tests often mirrors the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Each stage reflects a different facet of the frustration, exhaustion, and eventual resignation I experience as I try to navigate a system that was not built with neurodiverse thinkers in mind.

Denial: The System Can’t Be This Bad

When I first sit down to prepare for a standardised test, my initial reaction is one of disbelief—the system can’t really be this bad, can it? The sheer volume of information I’m expected to memorise and master feels overwhelming, and I find myself grappling with the randomness of it all. For a GLP like me, who learns and makes sense of the world by connecting patterns and meaning holistically, this avalanche of seemingly disjointed facts and concepts is disorienting. It feels as though I’m standing in front of an insurmountable wall, trying to find a coherent pathway through information that refuses to reveal any kind of meaningful structure.

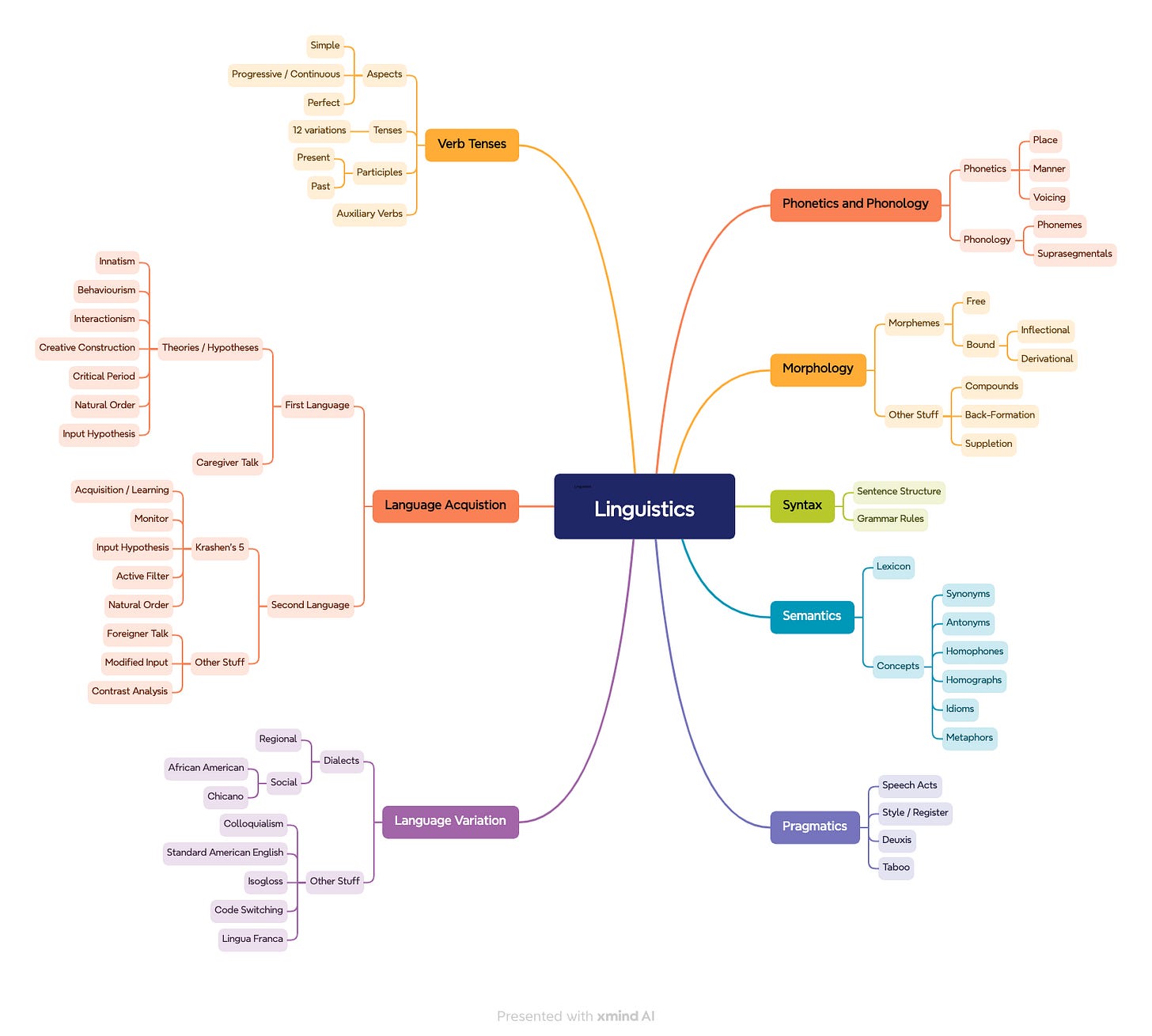

The mind map I created to study for this test perfectly illustrates the problem. It’s a sprawling web of categories, concepts, and details—verb tenses, phonology, syntax, pragmatics—all tangled together. For an analytic processor, perhaps this breakdown works. But for someone like me, the task of operationalising these fragmented pieces of information feels nearly impossible. It’s as if I am being asked to solve a puzzle without any of the edge pieces in place.

And yet, the system claims to be inclusive, to accommodate diverse learning styles. But from where I’m sitting, the reality for GLPs is far different. There’s no recognition of how we process information, no acknowledgment of the extra mental effort required just to make sense of the material. In this moment, denial is my coping mechanism—because if I truly acknowledge the task ahead, it’s hard to imagine moving forward at all.

Anger: Why Must It Be This Way?

As the reality of the test preparation sinks in, disbelief gives way to anger. Why must it be this way? The frustration isn’t just about the system being ill-suited for me as an autistic GLP—it’s about the fact that the very subject matter I’m studying, theories of language acquisition, doesn’t even acknowledge that GLPs exist. The course materials present these theories as universal truths about how humans acquire language, but they only reflect the experiences of Analytical Language Processors (ALPs). To be so completely unseen within the content of the coursework itself only deepens the sense of anger and distress. It feels as if the academic world is telling me that the way I process language—holistically, through patterns and meaning—simply doesn’t count. The knowledge being presented as “typical” is not reflective of all human experiences, only those of individuals from the neuro-majority.

What makes this even more frustrating is the predatory industry that profits from the struggles of neurodiverse learners like me. Test prep companies and tutoring services claim to have the answers, but they are merely profiting off the systemic exclusion of people like me. For those who can afford them, these services offer a band-aid solution, but they never address the deeper issue: the educational and testing systems themselves are not built to accommodate different cognitive processing styles. It’s an industry that thrives on making us feel inadequate, on convincing us that the problem is with us and not the system.

This leads to a pervasive feeling of being gaslighted. We’re told that these theories and tests are fair, that they represent universal human truths and abilities. But my lived experience tells me that’s a lie. The system refuses to recognise my way of thinking and learning, and that denial of my reality—of my very existence—turns the frustration into a deep, burning anger. This isn’t just about a test; it’s about the constant feeling of being unseen, misunderstood, and systematically excluded.

Bargaining: Maybe If I Try This Strategy...

As anger subsides, it often shifts into a phase of bargaining. Maybe, just maybe, if I try a new study strategy, I can find a way to crack the system. I convince myself that if I approach the material differently—perhaps by breaking it down into smaller chunks, trying to memorise facts in isolation, or following traditional test-taking strategies—I might be able to fit into this framework, even if it goes against how I naturally process information. I pour hours into outlines, lists, mind-maps, and even re-read chapters multiple times in an effort to break the content down into manageable pieces, hoping that this time something will stick.

But each time, it becomes apparent that these efforts are futile. These strategies—methods designed for ALPs—feel like they’re constantly working against my brain’s natural tendencies. They aren’t addressing the core problem: the system itself is broken for people like me. These are all workarounds that momentarily ease the panic and anxiety but never lead to true understanding or mastery of the material. My brain doesn’t work by compartmentalising facts—it needs the larger context, the patterns, the interconnectedness of ideas. But the testing structure doesn’t allow for that, forcing me to adapt in ways that feel unnatural and, ultimately, unsustainable.

This bargaining stage reflects a kind of hopeful desperation. I try to convince myself that if I just try harder, or use a different strategy, I might somehow overcome the system. But deep down, I know that no amount of studying will change the fact that the system wasn’t built with GLPs in mind. It’s exhausting, emotionally and mentally, to constantly seek solutions to a problem that lies within the structure, not within me.

Depression: The Weight of the Autism Tax

As the cycle of anger and bargaining gives way to reality, a deep sense of depression sets in. This is the weight of the autism tax—the extra emotional, cognitive, and often financial burden that I’m forced to pay just to keep up with a system that wasn’t built for me. No matter how hard I try, no matter how many hours I spend trying to break the material down into pieces my brain can handle, the return on my efforts is minimal. The constant struggle leads to a kind of burnout that is hard to describe, a feeling of running on empty while knowing the finish line keeps moving further away.

The emotional fatigue becomes overwhelming. Even when I’ve put in my best efforts, the results rarely reflect my true abilities. Instead, they reflect a system that measures how well I can mask my neurodivergence, not how much I’ve learned or how capable I am. It’s disheartening to realise that, despite all the effort I’ve put in, I’m being measured by a standard that simply wasn’t designed for someone like me.

For those who can afford additional support—private tutors, test-prep services—the burden is slightly lighter. But for those of us who can’t, the inequities of the system feel even more punishing. The resources available to help navigate these tests are part of an industry that profits off our struggle, creating another layer of exclusion. The autism tax is not just about effort; it’s about how much more we have to pay, in every sense, just to survive in a world that refuses to accommodate us.

Acceptance: Passing Doesn’t Mean the System Works

As I move into acceptance, it’s not the kind of acceptance that brings peace or closure. Instead, it’s a resigned acknowledgment that, for now, I have to navigate the system as it is to achieve my personal goals. The reality is that I need to pass this test, and there are more tests ahead, each one posing the same challenges. Passing doesn’t mean I’ve conquered the material in a meaningful way or that the system has suddenly become more inclusive—it simply means I’ve found temporary workarounds to get through.

For GLPs like me, we develop strategies to survive these tests. Maybe it's focusing on certain key areas we know will be tested, or using mind maps and our naturally occurring anticipatory anxiety - our brains overheating as they frantically sort through thousands upon thousands of potential scenarios and crappy test questions - just to get the facts in our heads long enough to regurgitate them. We become adept at finding shortcuts that help us play the game, but these aren’t solutions—they’re survival tactics in a system that doesn’t recognise our way of thinking. It’s frustrating because these strategies are about getting through the test, not about real learning or understanding. I know I’m capable of deep, holistic thought, but the test isn’t designed to capture that.

In accepting this reality, I also accept that passing the test doesn’t validate the system. It’s just a hurdle I have to clear. Each time I face a new test, I know the cycle will start again—the denial, the anger, the bargaining, the depression. Acceptance, in this case, is simply the recognition that, for now, I have to play by these rules to reach my goals, but that doesn’t mean the rules are fair, just, or fit for purpose. It’s about survival, not success.

The Bigger Picture: The Call for Systemic Change

As I reflect on the experience of navigating standardised tests as a neurodiverse individual, it becomes clear that the issue is much bigger than just my personal struggle. The system itself is deeply flawed, designed to cater to a narrow definition of learning and intelligence that excludes so many, especially GLPs like myself. It’s not enough for me, or others like me, to simply find ways to “get through” these tests. What we truly need is systemic change—an overhaul of the way education and testing are structured to be more inclusive of neurodiverse individuals.

The current standardised testing model is built around assumptions that all students process information in the same, analytical, linear way. This not only overlooks the strengths of GLPs but actively marginalises us. Tests should be designed to assess real understanding, the ability to make connections, and deeper thinking—qualities that GLPs naturally excel at. Yet, instead, we are forced to fit into a system that measures surface-level memorisation and time-based performance.

The predatory industries that profit from this exclusion—tutoring services, test prep companies, and educational programs—thrive precisely because the system remains unchanged. These companies offer expensive workarounds for those who can afford them, but they’re not genuine solutions. In fact, much of their profit is laundered into lobbying efforts to prevent any meaningful reform. After all, real change would threaten their business model. Inclusive testing models, ones that reflect the diversity of how humans learn and think, would reduce the need for these costly services. The current system, with all its inequities, ensures their continued success at the expense of neurodiverse students. What we need are assessments that don’t penalise us for processing information differently, but instead honour the unique ways we make sense of the world. However, as long as these industries have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, true reform remains an uphill battle.

The call for systemic change is urgent, especially in the face of neoliberal and neocolonial efforts like Project 2025. Education and testing systems should accommodate all learners, not just those who fit the narrow neurotypical mold. Yet, instead of moving toward inclusivity, Project 2025 is set to double down on this exclusionary legacy. It ravages the public education system, prioritising well-connected donors and corporations while sidelining the needs of students. Monopoly standardised testing companies eagerly support Project 2025 because its push for “standards-based” instruction means more money in their pockets. The more entrenched these standards become, the more they profit from selling testing services that reinforce the very inequities they claim to assess. Instead of dismantling these outdated frameworks, Project 2025 reinforces them, ensuring that education continues to be a tool of exclusion for all but the privileged few. We must replace these systems with structures that embrace diversity and recognise the full range of human intelligence—or risk deepening the divide even further.

Final Thoughts …

As I reflect on the emotional journey of preparing for and navigating standardised tests, it becomes clear that this process mirrors the stages of grief. From the initial denial of the overwhelming task at hand to the deep anger at a system that fails to recognise or accommodate neurodiverse individuals like GLPs, the experience is exhausting. The futile bargaining with strategies designed for ALPs eventually leads to the heavy weight of depression, as we pay the emotional and cognitive “autism tax” just to survive in a world not made for us. Even reaching a place of acceptance—where we acknowledge the need to play by the system’s rules—offers no real comfort. Passing these tests doesn’t validate the system; it only proves our resilience in navigating a flawed, exclusionary structure.

For neurodiverse students, this journey is not just about surviving one test but about continually confronting a system that denies our very way of processing and understanding the world. This isn’t sustainable, nor is it just. Standardised testing, as it stands, excludes, marginalises, and profits off those who struggle the most within its rigid framework.

The need for systemic change is urgent. We must advocate for an education system that recognises the diverse ways humans think and learn. Passing these tests may be necessary for now, but it shouldn’t be seen as a validation of a broken system. It’s time to push for reform—reform that dismantles outdated structures and builds an inclusive, equitable system where all students can thrive.