The MIT AI Brain Study Didn’t Measure What It Thinks It Measured

Cognitive Debt or Capital’s Demand? What the MIT Brain Study Misses About AI Use, Writing, and Work

The MIT brain study warns of AI-induced “cognitive debt.” But it misses the real story: not failing minds, but workers adapting to survive under capital’s endless demands. The problem isn’t AI—it’s the system that makes AI necessary.

Introduction: The Viral Panic

Kosmyna, N., Hauptmann, E., Yuan, Y. T., Situ, J., Liao, X.‑H., Beresnitzky, A. V., Braunstein, I., & Maes, P. (2025, June 10). Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of cognitive debt when using an AI assistant for essay writing task (arXiv:2506.08872v1) [Preprint]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.08872

It began, as these things so often do, with a headline that demanded I feel alarmed. The first brain scan study of ChatGPT users. Terrifying, they said. The human brain collapsing under the weight of its own shortcuts, neural connections decaying like the neglected wiring of some once-grand machine. Cognitive atrophy. The death of writing itself. The viral posts spread like wildfire across LinkedIn and elsewhere, each one straining for greater urgency than the last. AI is making people stupid, they whispered. Or sometimes shouted. Look at these poor fools who let the machine do their thinking. Look how quickly their minds unravel. A cautionary tale, cloaked in the language of neuroscience, its moral panic dressed up as empirical truth.

And yet, as I read—curious, of course, because I cannot resist these things—I felt a familiar tug. The same tug I always feel when the story being told seems a little too tidy. A little too eager to declare the problem located safely inside the individual. Lazy writers, they said. Weak-willed. Dependent. Incapable of the noble struggle real writing demands. And in that framing, I saw the pattern that always lurks beneath these sorts of stories. The puritanical drumbeat of productivity culture, where suffering is virtue and ease is sin. The generational anxiety that recycles itself with every new tool, every shift in technology, always certain that this time, this time, the young really have lost something essential. And the self-reliance myth, ever loyal to its role, wagging a stern finger at those who dare adapt rather than endure.

But as I read deeper into the study itself, what struck me wasn’t what they found. It was what they didn’t ask. The hollow space where the most obvious question should have been. Why? Why were these participants using AI in the first place? Why reach for assistance at all? The silence around that question was loud enough to ring. And in that emptiness, the real story began to take shape—not one of failing brains, but of a system that demands ever more from bodies and minds already stretched thin, a system that offers tools not as gifts, but as lifelines. The pattern lives there, in the space the study never quite dared to enter.

Three Moral Frames Driving the Public Narrative

The narratives arrive in familiar shapes, like old players reprising well-rehearsed roles. First, of course, comes the hymn to discipline. The Puritan logic of productivity, evergreen in its moral certainty: hard work is virtue, ease is decay. Writing must hurt to be real. One must wrestle with the blank page, bleeding onto the keys, anything less is dishonourable. And so, AI assistance is framed not as tool but as vice—an indulgence for the weak-willed who cannot bear the honest labour of thought. What amused me, though, was watching this sermon delivered, again and again, by voices that once outsourced their own writing freely. Retired executives, reminiscing on the purity of their struggle, whilst quietly omitting mention of the secretaries and typists who ghostwrote their reports, polished their memos, drafted their speeches. Senior attorneys, eager to denounce the moral decay of AI, somehow forgetting the decades spent signing their names to briefs crafted entirely by junior associates. The ghostwriters have always been there. What offends, perhaps, is not the offloading itself, but who now gets access to it.

Then comes the generational refrain, as reliable as the seasons. The decline narrative. A fresh wave of young people who, we are told, cannot write, cannot think, cannot function. It has been thus with every technological shift, and now AI offers a new villain. Neuroplasticity—the brain’s remarkable ability to adapt—is misread as irreversible loss, as if any shift in process signals a fall from grace. The irony, always rich, is that many of these laments arrive via social media posts riddled with broken grammar, incomplete sentences, and the kind of writing one would hesitate to hand in for a school assignment. From people who never made their living by words, who never felt the weight of written clarity as survival. Yet here they are, confidently diagnosing decline.

And finally, the self-reliance myth circles back to close the loop. The comforting story that all failure is personal. If you’re dependent on AI, it’s because you chose poorly. You lacked grit. You took the easy road. This framing, of course, requires a careful blindness to the conditions that drive such choices. The workload that expands without limit. The deadlines that shrink. The jobs that multiply in complexity whilst resources thin. The quiet burnout that accumulates when one is expected to carry not only their own tasks, but the administrative flotsam once handled by now-eliminated support staff. It ignores, too, those who come to AI not from laziness but from need—from disability, from executive dysfunction, from linguistic barriers, from chronic exhaustion, from neurodivergent processing that makes language itself a terrain of unpredictable demand. In this moral frame, none of that matters. You chose wrong. The fault is yours.

The Omission: The Glaring “Why” The Study Never Asked

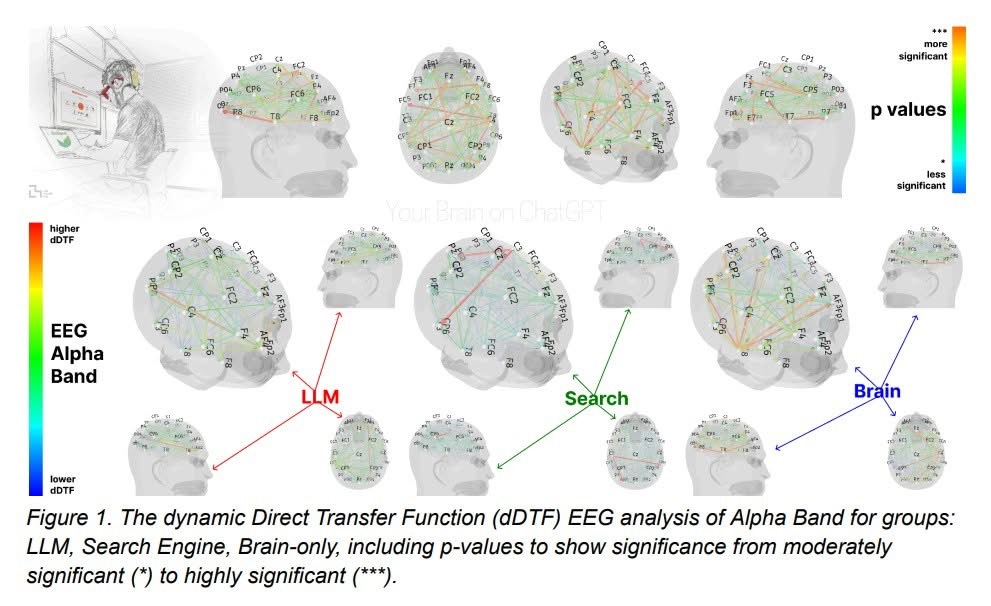

And yet, for all its careful diagrams and coloured brain scans, the study itself remains silent on the question that hovers largest. Why? Why reach for these tools? Why offload at all? The participants sit hooked to their electrodes, their neural connectivity charted and compared, but their circumstances — their stories — remain entirely unexamined. As if the choice to use AI arises in a vacuum, unshaped by the pressures bearing down on those who write.

The list writes itself, if one is willing to see it. Time scarcity, first and foremost — the creeping theft of hours as tasks multiply and resources contract. Job insecurity, where every deliverable must arrive faster, cleaner, and more polished than the last. Educational trauma, for those who carry the weight of classrooms that failed them, whose relationship with writing was bruised long before AI entered the scene. Executive functioning challenges, where the act of organising thought into structure becomes itself a steep hill. Language barriers, where fluency sits always just out of reach. Neurodivergent processing needs, for whom language arrives differently—gestalt, nonlinear, associative—requiring translation even within one’s own mind. And always, corporate productivity pressure, that unrelenting hum: more, faster, cheaper, now.

In such conditions, cognitive offloading is not failure. It is adaptation. It is a system quietly redesigning itself in response to unbearable load. The brain, brilliant and plastic, doing what it has always done: finding a way to survive. And still, the scolds persist. They sneer at this shift in much the same way their predecessors once grumbled at the abandonment of the handwritten letter, as if the transition to typed notes marked some irreversible cultural loss. As if efficiency and accessibility could never be virtues. As if technology’s history were not already filled with tools that once scandalised and now serve without comment. The typewriter. The word processor. Spell check. And now, the language model.

The study never asks why, perhaps because to ask would be to admit that the real cognitive debt isn’t owed by the users at all.

A Brief Recent History: AI and Labour Replacement

The story, of course, did not begin with this study. Nor with ChatGPT. The rise of AI-fuelled labour substitution follows a pattern far older than any neural connectivity map can capture. In the early months of LLM availability, stories began to circulate—at first quietly, then with growing fascination—of workers juggling multiple full-time jobs, using AI to fulfil tasks across positions, industries, even continents. Writing reports, drafting presentations, answering emails, generating code. Entire careers stitched together by language models and careful deception. Overemployment, they called it. A kind of opportunistic arbitrage of one’s own cognitive surplus.

But to frame this as simple opportunism misses the deeper contradiction. This was not sloth or indulgence. It was survival. Workers, squeezed by rising costs of living and stagnant wages, faced ever-expanding demands. The tasks multiplied; the hours did not. In such a context, AI became not luxury but lifeboat—a means to stretch finite energy across infinite expectation. As Marx would remind us, capitalism is driven always to extract more surplus value from labour, endlessly seeking new efficiencies, regardless of what becomes of the worker in the process. The language model was simply the next tool made available for that extraction—first seized by the workers themselves, briefly and rebelliously, before capital reasserted its claim.

The backlash arrived swiftly. Companies fired those discovered managing multiple jobs; new policies forbade unauthorised AI use; surveillance tools expanded under the banner of integrity and compliance. The bosses were not scandalised by the outsourcing of cognition per se—they had long outsourced and automated where it served their interests. What disturbed them was not the offloading of work, but the wrong people doing the offloading without permission.

There is a historical rhyme here, familiar to anyone who has read their Lenin or Mao. Every technological advance sharpens capitalism’s internal contradictions. Labour-saving devices, promised to free humanity from toil, instead become tools of discipline and control when captured by capital. As Mao warned, “wherever there is struggle there is contradiction, and wherever there is contradiction there is struggle.” The contradiction here is naked: technology that could reduce human suffering instead tightens the treadmill of production. The worker adapts to survive; the system punishes the adaptation.

The MIT study observes individuals offloading cognitive load, but it refuses to look up, to widen its gaze to the machine of accumulation driving these choices. It is as if we had studied the proletariat’s exhaustion under industrialisation by measuring muscle fatigue, whilst ignoring entirely the factory bell and the owner’s ledger. The neural data becomes a kind of scientific theatre, reducing social violence to private pathology.

The Larger Game: AI, Capital, and Labour Elimination

The AI companies know exactly what they are doing. Let us dispense with the polite fiction that these technologies emerged simply to assist workers, to free us from drudgery, to democratise access to knowledge. The true project lies elsewhere, written plainly in every investor report and quarterly forecast: to sever labour from production. To reduce or eliminate entirely the costly, troublesome, organising body that is the worker. And so the great wager unfolds.

The capital poured into these language models is staggering—billions sunk into data centres, chip manufacturing, engineering teams, and ceaseless model refinement. But these costs are not borne with concern; they are an investment made with the expectation of a far greater prize: the permanent enclosure of cognitive labour under corporate control. What once required salaried writers, editors, coders, paralegals, consultants, instructors — each with salaries, benefits, bargaining power — can now be replicated by a server rack drawing from a distant power grid.

And that grid is straining. The environmental cost sits largely unspoken beneath the techno-utopian promises. The water required to cool the processors. The electricity pulled from already stretched municipal systems. The heat expelled into communities that will never share in the profits. The toxic waste. In Memphis, the NAACP prepares to sue Elon Musk’s xAI over air pollution and resource extraction, a microcosm of the broader pattern: resource colonialism reborn in data form, where the land is strip-mined not for ore but for computation.

The climate cost is quietly externalised, much like the human cost. For what happens to the displaced? Where is the conversation about universal basic income, about housing as a right, about restructuring work when entire sectors vanish overnight? There is none. The worker is discarded, made redundant not simply by technical progress but by deliberate design. As Marx warned, “the instrument of labour, when it takes the form of a machine, immediately becomes a competitor of the worker himself.” And here the machine is not mechanical, but linguistic—yet the outcome remains familiar.

Even the term “assistive AI” functions as misdirection. This is not about assisting the worker; it is about controlling the conditions under which labour occurs, about who profits from its reduction, and who bears the ruinous weight when it succeeds. Capitalism does not mind labour-saving technology — it only minds when labour retains the benefit. Here, it seeks instead to retain the surplus for itself.

The MIT study cannot speak this truth. Its frame is too narrow, its methods too conveniently apolitical. It gazes inward, measuring connectivity, noting reduction, implying weakness, while the larger machine continues to grind onward, indifferent to the neural signals of those beneath its wheels.

What This Means for Studies Like MIT’s

And so we arrive at what feels, by now, almost inevitable. The study cannot ask these questions. Perhaps it dares not. This is not unusual. We have grown accustomed, almost numb, to these omissions from the grand institutions. The elite universities, for all their claims to fearless inquiry, remain bound—structurally, financially, ideologically—to the very engines driving these conditions. Their research agendas float downstream of capital’s currents, their endowments swollen by the same industries whose consequences they politely decline to name. One learns, eventually, where not to look, which questions are best left unposed if one wishes for one’s grants to be renewed.

Neuroscience, in particular, offers an elegant kind of refuge. It allows the study of suffering without ever confronting the systems that produce it. It reduces the vast, grinding machinery of labour, exploitation, and class into the quiet hum of individual brain waves. The worker’s exhaustion becomes a matter of alpha-band connectivity; their precarity rendered into colourful plots of neural coherence. The social evaporates; the biological remains. It is tidy. Contained. Comfortable.

And here, the notion of “cognitive debt” emerges as the perfect ideological device. On the surface, it appears neutral—even empathetic—a kind of sympathetic warning about the costs of dependence. But beneath, it functions as a shield, diverting attention from structural violence toward individual failing. You, the worker, have borrowed too much. You chose poorly. You surrendered your cognitive discipline to convenience. The system? The system remains unexamined, unindicted. It is not that capitalism demands more than human cognition can sustainably provide—it is that you failed to maintain your neural fitness for its demands.

The study maps the symptoms whilst averting its gaze from the cause. And we, who have seen this play before, are left with the familiar ache of what remains unsaid.

Conclusion: What We Should Be Asking Instead

In the end, the questions offered by studies like this one are simply too small for the moment we inhabit. It was never about whether people are getting dumber. The better question is: why have we built systems that force people to offload cognitive labour just to survive? It was never about whether AI is weakening our brains. The question is: what happens when an economic system demands more than human cognition—more than any healthy nervous system—can sustain?

The neural scans tell us only that people adapt. Of course they do. Adaptation is the oldest human skill. But adaptation under duress is not choice; it is coercion shaped by structures that have long since slipped beyond individual control. The real debt here is not cognitive—it is systemic. It is the debt extracted from every worker forced to sprint just to remain in place while the treadmill accelerates beneath them.

And perhaps, I cannot help but wonder, it is precisely this kind of deeper enquiry—into power, into capital, into class—that now so alarms certain factions of the State. Perhaps this is why we see, with rising frequency, the muttering campaigns against the “scourge of communism,” the calls to ban Marxist studies, the relentless conflation of any structural critique with subversion. They rail against something they do not even care to understand, so reflexively allergic to any lens that might reveal the mechanics of their own rule. To interrogate capital is to make visible its contradictions, and visibility remains the one thing power cannot easily withstand.

So let us ask the larger questions, the ones that ripple outward from these small, polite studies. Not because we seek comfort, but because we seek accuracy. We should not shame those who reach for tools to survive. We should indict the system that made those tools necessary.