A Mother’s Day reflection on the extraordinary women who raised me, walked beside me, and shaped the woman I’ve become—from Toronto to LA, from silence to voice, from survival to legacy. This is for them. And for you.

Ancestral Hands — Jean, Thomas, and the Line We Come From

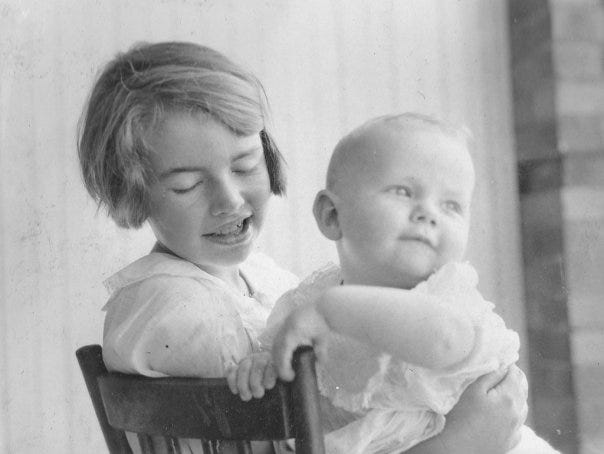

There’s a photograph I keep close. It’s black and white, soft with age, and in it my grandmother—Jean Allan—is no more than a girl herself, cradling her baby brother Sandy in a high-backed chair on a shaded verandah in Toronto. Her eyes are wide open, bright and cheerful, and there’s something to her mouth—a trace of a smile, or maybe the beginning of a laugh. Sandy, plump and unaware, leans back, his head turned toward the light of the sunlit suburban street. There’s nothing particularly grand about the image, nothing posed or monumental. But it tells the truth plainly: even as a child, she was already holding others.

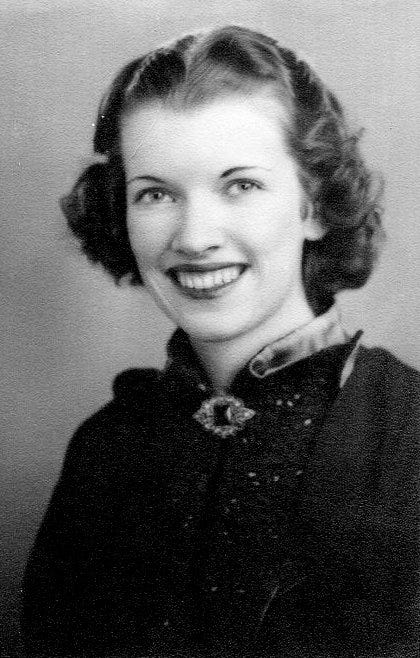

That was Toronto, before the war, before food scarcity and blackouts, before the state demanded that women empty themselves in service to the nation and then politely step back into the margins. She did not. Or rather, she did—but not in the way they intended. She married, yes—my grandfather—and had children there in Toronto, both daughters born into the steady rhythm of a life in the shadow of war. But when that marriage cracked under the weight of whatever was unspoken between them, she left. That alone was a kind of quiet mutiny. To walk away from a husband, across borders no less, and refuse to unravel.

She remarried briefly, but that too dissolved. No dramatic fallout—just a woman deciding she would not bend her life to fit the shape of another’s expectation. The family migrated to Los Angeles when my aunt was a teenager and my mother still a girl. It was there, in her forties, that she enrolled at Cal State LA. A wee woman abroad, starting again. No roadmap. No precedent. She earned her degree, then a master’s in social work, and began work with what is now known as LA’s Department of Children and Family Services—quietly, steadily, becoming the kind of person institutions depend on but rarely reward. The kind who doesn’t demand attention but cannot be done without. For a time, she ran the social welfare office embedded in the Imperial Courts housing estate, doing the kind of work that never makes headlines but keeps lives afloat. She was there during the Watts Uprising, or what we now call the Watts Riots—present not as authority, but as anchor. Holding ground. Bearing witness. Offering what little structure could be offered amid fire and fury.

I did not know this version of her well—not when I was young. I knew the later years—the worn cardigan years, the floral mugs that always seemed to hold a wee dram of rum or Crown Royal, the sharp eyes and upright posture of a woman who had never once allowed the world to bend her. But I’ve come to understand the earlier ones more now. The steel beneath her piercing eyes. The long view. The way she built her life with nothing more than conviction and the will to keep moving forward.

Her father, Thomas—my great-grandfather—had no such luxury. A man of principle, he was swept up in the Red Clydeside movement in Scotland, when workers dared to demand dignity from the empire. For that, he was removed like a weed from the soil, deported to Canada, where they thought he’d be less dangerous. Perhaps he was. Or perhaps he simply taught his children that power should always be challenged, even if it costs you everything. I wonder what he’d make of us now, all these generations later—dispersed across continents, carrying degrees and contradictions, still bristling under systems that expect obedience in exchange for survival.

We didn’t wander. We were scattered. That’s something empire never admits—that displacement is not just the loss of land, but the shattering of lineage. They call it migration, or adoption, or assimilation, but it’s always rupture. Always someone deciding that kinship can be rearranged by paperwork. I was taken from my mother before I had words to name the world, just a toddler. Taken by the same department my grandmother worked for. And somehow—through a twist of bureaucracy or mercy or sheer will—she stayed in my life. As grandmother, but not fully, though never absent either. A figure at the margins. Always there, and never allowed to say how or why.

She held the lie for decades—that I was born into the family that raised me. A fiction enforced by courts and sealed records and the unspoken fear that if the truth surfaced, everything might come undone. I think it frightened her more than it freed her. So she kept it. Carried it. Perhaps out of guilt. Perhaps out of survival. I can’t know.

My mother and I did eventually find our way back to each other, though not quite to closeness. I think something broke in her long before I was born, and the wound never closed. I cannot begin to imagine what it means to lose your child to the state and be forbidden to reach for them. What that does to a person’s sense of worth, of voice, of time. She built a life again—married, had more children. From that later chapter of my mother’s life, I gained a sister—one of the fiercest women I know. After divorcing young, with two children in tow, she charted a path few would have dared. She studied nursing late into the night whilst raising them on her own, eventually becoming a nurse practitioner. Somewhere along the way, she found me—and found love again, marrying her now-husband, a man who honours her strength. Her daughter, now grown, carries the spark of our grandmother so clearly it startles me sometimes—same fire, same wit, same quiet command of a room. Another thread in the tapestry. Another woman who turned survival into structure, and did it with grace.

And me—I used to believe I stood apart from it all, floating just outside the family line, disconnected by the violence of adoption and the silence that followed. But now I see it differently. I don’t stand outside it—I am it. All the contradictions, all the resilience, all the scars and soft landings. I belong to the same pattern. Not an inheritance in name or title, but something older. Something passed hand to hand, glance to glance. A kind of memory that doesn’t need telling to be known.

It took me decades to realise that I, too, am made of that same stubborn love. That same bone-deep will to carry on, even when the world won’t name you rightly. And now, I carry it forward—in my voice, in my children, in the way I write things down that were once only held in silence.

A Woman Becoming — My Own Arrival in the Line

I used to think of Sandy—my great uncle, though I never once called him that—as someone from another world entirely. I was six when I met him, just once, and back then I had no usable language to match the weight of such a moment. No words for family, for wonder, for belonging—not yet. A kind of living legend in our family. Brilliant, gentle, deeply innovative. An engineer by training, but really something much broader. A problem-solver, a witness, a quiet builder of order in a world full of chaos. He worked for the Defence Research Board of Canada, then was a a Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Toronto, and later became one of the few people in the world considered an expert in a certain model of car as it related to motor vehicle collisions. This knowledge, with his own company, took him across North America, into courtrooms and conference rooms. He wasn’t flashy. But when a problem arose, people called Sandy. I suppose they always knew he’d bring clarity.

That encounter left a massive impression—one I’d later write about in No Place for Autism?. I was a child in a poor family, bursting with the autistic urge to wander, to explore, to chase every question to its edge—but there was no money for any of that. And then came Sandy: a man who travelled the world not for leisure, but because people paid him well to solve problems. It was epic. A revelation. I had no words for it, of course—not then. But I grasped the shape of the story. Get really good at solving puzzles, and the world will come calling. Be so useful they send for you. It was the first roadmap I’d ever seen. I didn’t know I was following a thread. But I was.

I became a forensic scientist—a specialist in audio, video, and image evidence. I taught internationally, wrote the guidebooks and built the curricula others would use—all whilst I was still gaining fluency in English literacy myself. In truth, it was a kind of self-directed occupational therapy, social engineering, and crowd-sourced belonging rolled into one. I wrote to figure out how things worked, and in doing so, made space for myself in rooms I hadn’t yet been invited into. Every chapter, every manual, was a foothold—language made visible, knowledge made claimable. I didn’t just document the field. I helped to shape it, whilst quietly learning how to shape myself. I helped build an entire discipline from fragments and intuition. From chaos, I crafted method. Like Sandy did. Like Jean did.

But for a long time, the world insisted on reading that story through the wrong lens. All those accomplishments—international lectures, court testimonies, accolades—were praised as the triumphs of a so-called renaissance man. That phrase always rang hollow. As though mastery and versatility could only be male. As though surviving a hostile world with grace and innovation was somehow novel when done by someone assigned male at birth. But it wasn’t novelty. It was inheritance. I was never a renaissance man—I was a queer woman surviving in plain sight. Learning to do what needed doing. Carrying the line forward.

That’s the thing no one tells you about transition. It doesn’t always feel like discovery. Sometimes it feels like confirmation. Like finding the blueprint and realising you’ve already built the house. The scaffolding was always there. The instincts, the endurance, the devotion to care and craft. The voice, muffled for decades, was finally my own.

My work was never the outlier. It was the continuity. My grandmother changed the system from inside, one child at a time. Uncle Sandy made machines more humane, more knowable. My sister, the life saver—who once dropped everything and crossed two states to be by my hospital bedside, not out of obligation, but because it was me, and she was she. And I—I’ve spent a lifetime helping things go right. Whether in a lab, a courtroom, or a classroom, that’s what I’ve done. Not because I was brilliant. Because I was kin.

And now, finally standing fully in myself, I can see that the next act had already begun. Not just in me, but beside me. In the one who’s held the line beside me all these years. The one who builds belonging not from theory, but from touch. From repetition. From love.

The Architect of Belonging — My Wife, the Builder

There are no photos that fully capture it—no portraits of her at the kitchen table with curriculum spread out like a cartographer’s map, no time-lapsed footage of her slowly realising that none of the systems built by others were built for our children. She was a trained primary school teacher, college-educated, patient, intentional. She could have returned to the classroom, sought accolades, taken the path that looks so respectable on paper. Instead, she stayed. And built something better from scratch.

She homeschooled our neurodivergent children before that language was even fully available to us. Not because she believed in isolation, but because she believed in them—and she believed in learning. Not the packaged kind, the “school in a box” kind, but the messy, relational, deeply human kind. She didn’t become a teacher in our home. She became a living IEP. Not a document, but a daily practice of adapting, observing, trying again. She learned and unlearned and learned again—alongside them, not ahead of them.

Now, with our children older, she volunteers twice a week at the local charity shop that funds the mountain animal shelter. She sorts, stewards, uplifts. She brings the unsold but still useful items into the community—not just to give things away, but to notice what people need before they ask. And she brings the children into it as well. Each contributes in their own way—one might organise the shelves, another might carry bags or or test the donated electronic items before their sale. No forced roles. Just strength-based inclusion, the ethos of our family made visible. It isn’t a lesson. It’s just what we do.

There are no titles for what she does. No paycheques or plaques. She’s not in the spotlight. But she is the orbit. The one around whom all of it coheres—not through force, but through constancy. Through love that is logistical, calendrical, practical. Through care that is never performative but always profound.

We’ve shared nearly thirty years together—partners in every sense. No dominion. No hierarchy. Just a long, quiet yes. A life built not from roles, but from reciprocity. I often marvel at it, not because it’s extraordinary, but because it’s been so steady I almost forget the world doesn’t often work this way.

And now, I watch her at the shop—shoulders squared, hands always moving, our children flanking her like moons in quiet orbit. Each task—a shelf arranged, a bag carried, a story listened to—becomes a thread in something larger. There’s a stillness to her, not inaction but rootedness. A kind of Slavic constancy that feels older than language, as though she remembers some ancient instruction about how to hold ground when the sky splits open.

Outside, the world stumbles on under the weight of the Tangerine Tyrant’s petulant wrath, his bloated grievance casting long shadows across policy and pocketbook. The institutions groan, the safety nets fray. The cruelty is deliberate now. And so charity becomes not a gesture, but a necessity. Not kindness, but infrastructure. What she offers—steadily, without spectacle—is what the state once promised and forgot: dignity, usefulness, a place to belong.

This, too, is a kind of mothering. Not celebrated. Not spotlighted. But sustaining. Enduring. The kind that makes everything else possible. The kind that reminds you: when the storm comes, you find the centre—and there she is.

Renaissance Men?

I saw a quote once, similar to that above. It read, “When a man is talented in many disciplines, we call him a Renaissance man. When a woman is, we just call her a woman.” It was meant to be clever, I suppose—wry commentary on the double standards baked into language. But the more I sat with it, the more I realised it wasn’t just commentary. It was testimony. It was a map of my whole life.

The things we revere in wealthy men—multidisciplinarity, adaptability, intellect, poise, leadership—we frame as exceptional, even mythic. But those very same qualities have lived all around me, worn in quiet, practical ways by the women I’ve loved. Not displayed like medals, but carried like tools. My grandmother, divorced in an era that punished women for leaving, started over, studied social work, and built a career helping families survive the very machinery that once tore mine apart. My mother, wounded and worn, still managed to rebuild a life and raise children. My sister, fierce and brilliant, charted her own course through medicine and motherhood. And my wife—well, I’ve said already what there is to say. She makes life possible.

None of them called themselves extraordinary. They would scoff at the word. But that’s only because no one ever handed them a title for what they were doing. No one gilded their resourcefulness, or wrote profiles about their tenacity. They were simply being women. Not in the shallow, gendered sense we’ve been taught to admire, but in the deeper, ancestral one. Woman as world-builder. Woman as lifeline. Woman as architect of continuity.

And here I stand, a trans woman, a daughter of this line. I spent years thinking I had to earn belonging through achievement—that if I just gathered enough accolades, publications, credibility, I might finally be allowed inside. That’s the logic of the outsider, and I’ve lived most of my life there—on the edge of language, piecing meaning together as a gestalt processor, trying to translate a world that was never designed with me in mind. It’s why I called my Substack The AutSide. Not just a play on words, but a home for all the things I was never quite given the space to say.

But I see now that the work was never about proving myself worthy. It was about returning to something I was born from. Something I carry forward now, not just in my own name, but in theirs. If what we call a Renaissance man is someone who moves across disciplines with grace and insight, then I have lived among Renaissance women my whole life. They just called it survival. They just called it Tuesday.

The myth of male genius has always relied on the erasure of female labour. But the women in my family—my grandmother, my sister, my wife—they didn’t wait for permission. They built. They adapted. They held the line. And now, finally, I do too.

Final thoughts …

Mother’s Day in America has always unsettled me. It’s wrapped in pink foil and brunch menus, mass-produced sentiment and supermarket carnations. There’s a card for every flavour of maternal archetype—except the real ones. The ones who stayed up all studying for their organic chemistry final. The ones who kept family secrets because the truth was too dangerous to speak. The ones who patched holes in the system with their own bodies, their own time. There’s a hollowness to it all. A ritual of performance: Here’s your chocolate, here’s your flowers—now get back to work for another year, Mum.

I wanted to break from that. To tell a different story. The true stories of the women who raised me—not always directly, not always easily, but always with a kind of sacred persistence. My grandmother, who refused to be defined by a single chapter of her life. My mother, fractured but still luminous in her way. My sister, steadfast and fierce. My wife, the architect of our every ordinary miracle. These are not the women who get TV specials or Hallmark campaigns. They don’t ask for attention. But without them, I would not be here. I would not be me.

I am the woman I am now because they showed me how to build, how to love, how to remain. And if you’ve come with me this far—through over 1,200 articles and audio reflections, through fragments and footnotes and open-hearted remembering—thank you. You’ve helped make this a space where truth can be spoken without needing to be simplified. Where stories like mine, like theirs, like maybe yours, can unfold in full.

This piece is for them, yes—for the women who carried me, shaped me, steadied me. But it’s also for you—for everyone walking their own version of this road, especially those on the AutSide. For the ones who carry the world and are told it’s just what women do. I see you. And I’m glad you’re here.