The Hidden History of Gestalt Processing: How Oral Traditions Shaped Language and Literacy

For most of human history, language has been a tool of simplicity and efficiency. Imagine a storyteller in a Gaelic village centuries ago, standing before an attentive audience, weaving together myths, histories, and lessons. Their words, carefully chosen, were not dissected into phonemes or parsed for grammar but were absorbed as a whole, their meaning conveyed through context and cadence. These oral scripts, often minimalist yet rich in intent, carried the weight of cultural memory and everyday communication. This approach to language, where meaning emerges holistically rather than through analytical breakdown, aligns with the Gestalt Language Processing (GLP) style—a natural, efficient way humans have used language for millennia.

GLP, with its reliance on scripts and gestalts, was likely the dominant way people interacted with language before the advent of widespread literacy. It thrived in oral cultures where efficiency was paramount, and the goal was to convey meaning with minimal effort. However, the Analytical Language Processing (ALP) style, introduced by literate colonisers, brought a markedly different approach to language and communication. Literacy, which breaks language into letters and sounds, prioritised analysis and precision, enabling the creation of detailed records, legal systems, and bureaucracies. This analytical style was highly efficient for organising large, complex societies and proved invaluable in helping imperialist cultures expand and maintain their empires. The ability to categorise, document, and standardise language in written form became a tool of control and consolidation, often at the expense of the oral traditions central to cultures like the Gaels. In these colonised societies, GLP and its rich oral storytelling traditions were marginalised, as the colonisers’ literacy frameworks reframed language as something to be studied, categorised, and systematised—a means of domination as much as communication.

The minimalist nature of GLP scripts mirrors a universal principle of language efficiency, which is mathematically described by Zipf’s Law. This law explains why the most frequently used words or phrases are short and simple, optimising communication for both speaker and listener. As we explore how GLP’s holistic style aligns with this principle, we uncover a story not just of linguistic evolution but of cultural erasure and adaptation. GLP’s efficiency was not an accident; it was a necessity—and understanding this helps us appreciate its historical significance and ongoing relevance in a world that often undervalues simplicity in favour of complexity.

Historical Context: Pre-Literate Societies and the Oral Tradition

For much of human history, oral transmission was the primary means by which language, knowledge, and culture were preserved and shared. In societies without written language, a rich oral tradition ensured the continuity of laws, values, and histories across generations. In Gaelic culture, key figures like the seanchaí, or storyteller, and the filí, or poet, embodied this responsibility. The seanchaí wove dynamic, contextually rich tales that carried history, moral lessons, and mythos, adapting their narratives to suit the needs of the audience and moment. The filí, by contrast, were elevated figures, blending their poetic compositions with legal, spiritual, and historical significance. Their precise, structured works were vital to the governance and identity of the community. These roles were central to the societal fabric, not mere entertainment but vehicles for survival, education, and cohesion.

In such oral societies, the Gestalt Language Processing style was not only well-suited but essential. GLPs naturally process language as gestalts—holistic scripts or chunks of language. This ability allowed them to faithfully recall and transmit vast amounts of information with remarkable efficiency. Gestalts, by their nature, capture the meaning and structure of language in context, making them ideal for preserving oral traditions across generations. The cadence, rhythm, and repetition inherent in oral storytelling complemented this processing style, enabling GLPs to internalise and reproduce complex narratives, laws, and teachings without needing to break them into smaller, analytical parts. This efficiency was not merely practical; it was vital, ensuring that knowledge remained intact even as it adapted to the nuances of context and audience.

However, the introduction of literacy, particularly in the form of colonisation and religious missions (redundant?), disrupted this balance. In Gaelic culture, as in many others, the Latin alphabet and written texts arrived with Christian missionaries. Literacy favoured an ALP style, which breaks language into discrete units—letters, phonemes, and grammatical structures—for study and analysis. This shift was transformative. Whilst the ALP style allowed for the detailed documentation of records, legal codes, and religious texts, it also imposed a rigid framework that devalued the oral traditions central to GLP societies. The dynamic, living narratives of the seanchaí and the structured, ritualistic compositions of the filí were overshadowed by the static authority of written texts. Oral cultures, once celebrated for their fluidity and adaptability, were reframed as “pre-literate,” - primative - their methods deemed less advanced.

The consequences of this cultural shift persist today. In the Global North, GLP is not recognised as a valid and natural language processing style but is pathologised as a Specific Learning Disability (SLD). GLPs, whose strengths once preserved entire bodies of cultural knowledge, are now seen through the lens of deficit. Education systems prioritise ALP methods, such as phonics and grammar analysis, ignoring the holistic and context-dependent ways GLPs learn and communicate. This erasure overlooks the profound contributions of GLP to human history. Oral traditions, often rooted in GLP strengths, were responsible for preserving sacred texts like the Torah, Talmud, and the Gospels of the Bible. These texts, whilst eventually codified in written form, owe their survival to generations of oral transmission, where GLPs likely played a central role in ensuring fidelity and meaning.

The marginalisation of GLP reflects a broader issue of cultural dominance. The Global North's elevation of ALP as the default processing style, coupled with the systemic devaluation of oral traditions, mirrors the colonial frameworks that prioritised literacy as a tool of control and empire-building. Yet, the history of GLP shows that this processing style is not a limitation but a powerful means of preserving and transmitting knowledge. In recognising the cultural and historical significance of GLP, we can begin to challenge the narrow frameworks of modern education and celebrate the diversity of human cognition that has shaped our shared heritage.

The Efficiency of GLP Scripts in Communication

GLP scripts are pre-formed chunks of language that convey meaning holistically, without breaking language into smaller, analytical components. For GLPs, these scripts are not constructed word by word or sound by sound but are absorbed and reproduced as cohesive units. A script might be as simple as “Can I have that?” or “What’s the time?”—phrases that are versatile and efficient, carrying significant meaning without requiring further elaboration. Even single words can function as gestalts, such as a toddler saying “up” to mean, “Pick me up,” or an adult responding with “sure” to convey agreement. These scripts allow GLPs to communicate effectively by relying on the inherent power of context and shared understanding to fill in the gaps.

This minimalist communication style reflects the efficiency prioritised in both oral traditions and GLP. In oral societies, where speed and memorability were essential, the ability to convey rich meaning with few words ensured effective transmission of knowledge across generations. Similarly, GLP scripts strip language down to its essentials, relying on the listener’s ability to infer unstated details based on context. For example, a GLP might use the script “I’m cold” to imply, “Can you turn up the heat?” or “Can I borrow a jacket?” This reliance on minimalism is not a limitation but a feature—an elegant strategy for reducing verbal effort whilst maximising communicative impact.

The efficiency of GLP scripts can be likened to the way modern technology compresses information. Take the JPEG format for images, which reduces file size by eliminating redundant data whilst preserving the overall look and feel of the image. Similarly, GLP scripts “compress” language, retaining its core meaning whilst omitting extraneous details. Just as a compressed image conveys the scene without requiring every pixel to be rendered in full, a GLP script conveys intent without spelling out every nuance. The redundancy that might exist in more elaborated communication—detailed explanations or explicit grammar—is replaced by reliance on shared context, much like how JPEGs rely on the viewer’s brain to fill in the visual gaps.

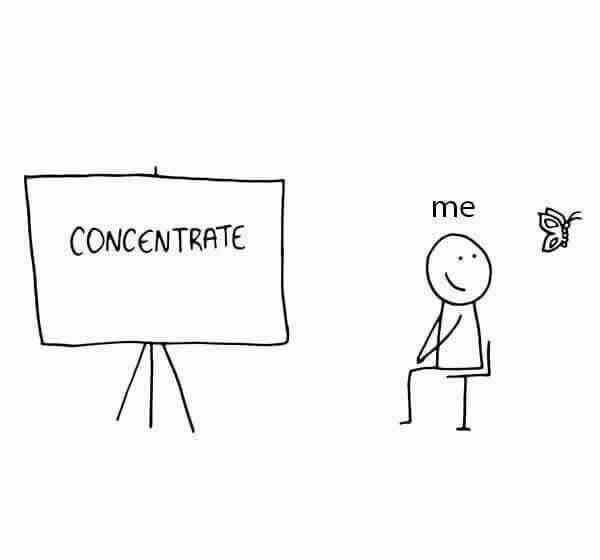

This minimalist, context-dependent approach is not limited to historical or oral traditions—it is alive and thriving in modern communication. Consider texting, which often favours brevity over formality. A text like “On my way” or even just “omw” conveys a complete thought, relying on shared understanding to fill in any missing details. Similarly, memes (see below) encapsulate entire ideas or emotions in a single image or phrase, often requiring the viewer to bring their own cultural knowledge to fully grasp the message. Both examples mirror the GLP reliance on scripts, where efficiency and shared context take precedence over explicitness.

These parallels highlight how GLP scripts are not an outdated or lesser form of communication but a natural and enduring strategy for conveying meaning. They prioritise economy and adaptability, allowing speakers to navigate diverse contexts with minimal effort. In a world increasingly shaped by digital and fast-paced communication, the principles underlying GLP—compression, reliance on context, and minimalist expression—are more relevant than ever. Far from being a deficit, GLP is a powerful processing style that continues to shape how humans interact, both in history and today. By recognising and valuing this efficiency, we can better appreciate the diversity of linguistic approaches that enrich our world.

Introducing Zipf’s Law: Language Efficiency Explained

Zipf’s Law offers a fascinating insight into the efficiency of language, illustrating how humans naturally organise communication to minimise effort. The law states that the frequency of a word is inversely proportional to its rank in a frequency list. In simple terms, the most commonly used word in a language, like “the” in English, appears far more frequently than the second-most common word, such as “and.” The third-most common word, perhaps “of,” occurs less frequently still, and so on. This pattern creates a predictable curve where a small number of high-frequency words dominate language use, whilst a much larger number of low-frequency words account for less linguistic real estate. This phenomenon reflects language’s inherent tendency toward efficiency—why waste effort on complex constructions when simple, high-frequency words can do the job?

Zipf’s Law is not just an abstract observation; it’s a principle of linguistic economy. By relying on a few high-frequency words to structure most communication, humans reduce cognitive load for both speakers and listeners. Short, simple words like “is,” “it,” and “you” act as scaffolding for sentences, enabling fluid communication without requiring excessive mental effort. This same principle can be seen in other areas of human behaviour, from city populations (where a few cities are vastly larger than the rest) to internet traffic (where a small number of websites dominate user visits).

This principle aligns seamlessly with the way GLP scripts are formed and used. GLP scripts, much like Zipfian high-frequency words, are concise, contextually powerful, and designed for efficiency. Frequently used scripts, such as “I don’t know” or “Can you help me?” are short and versatile, functioning as linguistic shortcuts that convey complete thoughts with minimal effort. They fit into the Zipfian pattern by appearing often and being adaptable across contexts, ensuring maximum communicative value with minimal verbal complexity.

At the other end of the spectrum, less frequent scripts or gestalts—those used in specific or uncommon contexts—tend to be longer and more detailed. For instance, a rare script like asking for directions might take the full form, “I need directions to the nearest train station,” or in German, Ich brauche eine Wegbeschreibung zum nächstgelegenen Bahnhof, and in Spanish, Necesito indicaciones para llegar a la estación de tren más cercana. However, in casual or slang usage, these scripts often simplify for efficiency, dropping articles and other elements, becoming, “Need directions to train station,” or in German slang, Brauch Wegbeschreibung Bahnhof, and in Spanish slang, Necesito direcciones estación tren. This streamlined form mirrors how low-frequency words in Zipf’s curve may still adhere to linguistic efficiency by retaining just enough structure to convey the essential meaning. Even in their longer forms, these scripts justify their complexity by carrying a heavier informational load necessary for less familiar contexts.

Zipf’s Law highlights the natural human inclination toward economy in communication, a principle that GLP scripts embody with remarkable clarity. By relying on a small set of highly efficient chunks of language, GLPs align seamlessly with the broader patterns of how language evolves to serve its primary purpose: to convey meaning with as little effort as possible. This principle transcends individual languages, as Zipf’s Law applies universally, whether the language is English, German, Spanish, or any other. Across languages, the most frequently used words and phrases are short and versatile, whilst less common ones become increasingly complex and specific, yet all are governed by the same underlying tendency toward efficiency.

GLPs harness this universality by constructing communication around high-frequency scripts that are quick to learn, easy to use, and adaptable across contexts. For example, a simple script like “I don’t know” in English aligns with “… weiß nicht” in German or “No sé” in Spanish—short, efficient expressions that carry significant meaning with minimal effort. Even as languages differ in structure and vocabulary, their frequent reliance on concise, high-utility phrases mirrors the Zipfian curve, where a handful of elements dominate in usage while others fill more specialised roles.

This connection underscores the validity of GLP as a processing style that is not only natural but rooted in universal linguistic principles. It demonstrates that GLP is not a deviation from language norms but rather a powerful expression of how all human communication optimises for meaning and efficiency. By aligning their processing style with the same principles that govern language itself, GLPs offer a unique lens through which to understand both the elegance and adaptability of human communication. Recognising this alignment challenges the misconception that GLP is a limitation and instead frames it as a valid, effective approach to language that resonates across linguistic and cultural boundaries.

GLP as the Default Mode of Language in History

Again, for much of human history, GLP was likely the dominant style of language use, perfectly aligned with the oral traditions that defined “pre-literate” societies. Language in these cultures was not written down but transmitted through spoken word, relying on holistic, efficient communication to preserve and share vital knowledge. Storytelling, ritual recitation, and oral law encoded vast amounts of cultural memory into gestalts—scripts that could be faithfully reproduced without needing to be broken down into smaller, analytical units. Many cultures for which we lack written records likely operated predominantly as GLP societies, where meaning was preserved and adapted through oral transmission. These oral cultures, however, remain underrepresented in historical narratives, as histories are often written by the literate victors—typically colonisers who introduced their ALP-driven frameworks to previously GLP-dominant societies.

The Gaels provide a vivid example of this transition. Their early communication systems, such as Ogham, arose relatively late, likely influenced by contact with Norse cultures. Unlike fully alphabetic systems, Ogham functioned as a set of logographs, where individual runes often carried whole meanings, making it more compatible with GLP’s preference for gestalts. For the Gaels, Ogham complemented oral traditions rather than replacing them, serving as a mnemonic aid or boundary marker rather than a comprehensive writing system. Oral storytelling and poetry, not writing, remained the primary means of preserving cultural knowledge. However, as literacy spread with the arrival of Latin-based systems brought by Christian colonisers, this balance began to shift.

The introduction of literacy disrupted the dominance of GLP by prioritising ALP styles, which focus on breaking language into discrete units like letters, phonemes, and grammatical structures. Literacy’s emphasis on written records and systematic analysis served the needs of bureaucracies, empires, and organised religions, making it a powerful tool for colonisation. In societies like the Gaels, where oral traditions had long been central, this shift marginalised GLPs by devaluing the holistic, context-driven communication that had sustained their culture for centuries. The poetic compositions of the filí and the dynamic storytelling of the seanchaí were overshadowed as colonisers first codified the language of the colonised, transforming it into something static and controllable, detached from its living, oral roots. Following this, they often imposed restrictions that prohibited both the use and transmission of the original language, effectively severing the cultural continuity that oral traditions had maintained. At the same time, they restricted access to literacy in the colonisers’ own language, forbidding the colonised from reading key texts like the Bible independently. This dual strategy—erasing the old language whilst controlling access to the new—ensured domination by suppressing both the heritage of the colonised and their ability to participate fully in the imposed system.

Yet, the strengths of GLP in oral cultures were profound. Unlike ALP, which prioritises structural precision, GLP’s holistic approach ensured that knowledge was preserved in ways that were meaningful, adaptable, and resilient. Oral traditions encoded not just information but the very essence of a culture—its values, relationships, and identity—into gestalts that could be reinterpreted and adapted as circumstances changed. This adaptability allowed GLP-dominant cultures to thrive for millennia, preserving continuity without the need for written records. For the Gaels, oral traditions carried the weight of history, law, and myth, shaping a communal identity that persisted even in the face of colonisation and cultural suppression.

I am reminded of my grandmother, who could recount historic events as if they had happened just yesterday. Her words painted vivid pictures of the past, weaving together personal memories with tales passed down through generations. She spoke with a reverence for Scotland's heritage, particularly the poetry of Robert Burns, whose works she would recite with heartfelt passion. Burns, affectionately known as Scotland’s Bard, was not granted this title by any official decree but by the acclaim of his fellow freemasons—a community deeply rooted in oral tradition. Like the seanchaí of old, freemasonry relies on the spoken word to preserve its rituals, forbidding the writing down of its sacred scripts to this day. Its rituals are passed through “instructive tongue and attentive ear,” an unbroken oral tradition that ensures knowledge is transmitted faithfully from generation to generation.

This living connection to oral tradition demonstrates the power and resilience of GLP in preserving cultural heritage. Just as my grandmother’s recitations of Burns’ poetry bridged centuries, oral traditions have kept history, identity, and values alive in ways that written records cannot fully capture. For the Gaels, this holistic and context-rich method of passing on knowledge provided a sense of continuity and adaptability that written texts, with their static nature, often lack. In the rituals of freemasonry, as in my grandmother’s vivid storytelling, we see how oral traditions remain a dynamic force, connecting the past to the present and carrying it forward to future generations. This resilience underscores the enduring strengths of GLP, where meaning is not fixed on a page but lives and evolves in the words we speak and share. Poems like Robert Burns’ A Parcel of Rogues exemplify this power, providing the sons and daughters of Scotia with a framework to interpret and understand contemporary events. Burns’ scathing critique of the betrayal that led to the Act of Union resonates anew as Scots reflect on the Crown’s recent actions to scuttle the Independence vote. Through oral recitation and communal reflection, such works continue to shape the identity and resolve of a nation, demonstrating how oral traditions and GLP empower people to draw strength and clarity from the past while navigating the challenges of the present.

Understanding GLP as the default mode of language for much of human history reframes how we view the transition to literacy. Rather than seeing oral cultures as “primitive” or incomplete, we can recognise the sophisticated efficiency and resilience of GLP, which prioritised meaning and continuity over the rigid precision of ALP. This recognition challenges the colonial narratives that have long framed oral traditions as inferior and opens the door to appreciating GLP’s enduring role in shaping human communication.

Modern Implications and Reclaiming Gestalt Processing

Modern education systems remain dominated by phonics-based and ALP methods, which fail to recognise the strengths of GLPs. These methods, rooted in the colonial and industrial prioritisation of standardisation, treat language as a series of building blocks to be broken apart and reassembled. This approach marginalises GLPs, whose natural strength lies in processing language holistically through scripts or gestalts. Educational practices rarely accommodate this, instead framing GLPs as deficient when they struggle with methods that are incompatible with their cognitive style. Such systems overlook the power and efficiency of GLPs’ approach, which thrives on context-rich communication and mirrors the principles of Zipf’s Law.

In my upcoming book, Decolonising Language Education, I delve into this struggle, challenging colonial legacies in English Language Development (ELD) and advocating for transformative practices. By honouring oral traditions, contextual learning, and Zipfian efficiency, we can create teaching methods that validate the natural strengths of GLPs. For instance, using scripts with high communicative value—“I need help” or “What’s the time?”—can form the foundation for language development. Incorporating home languages and cultural narratives further enriches this approach, fostering confidence and identity alongside language proficiency. Education must shift to support GLPs not as anomalies but as natural processors of language, representing approximately 40% of the current human population and reflecting humanity’s historical linguistic practices.

We see the relevance of GLP and Zipf’s Law in modern communication trends like emojis, memes, and internet slang. These minimalist, context-dependent forms of communication align perfectly with Zipfian principles, where high-frequency elements (like “lol” or a thumbs-up emoji) dominate due to their simplicity and efficiency. Memes, in particular, encapsulate complex ideas or emotions in a single image or phrase, relying on shared cultural context for interpretation. This reflects how GLPs leverage scripts, using concise, high-utility language chunks to convey rich meaning without unnecessary elaboration.

These modern trends highlight a broader resurgence of Zipfian principles in communication, suggesting that minimalist, gestalt-based approaches are not relics of the past but vital tools for navigating the complexities of the present. They remind us that GLPs are not only aligned with linguistic history but also with the future of human communication. By recognising this, we can reframe GLP not as a challenge to overcome but as an essential, efficient, and culturally rooted way of engaging with language.

Final thoughts …

Gestalt Language Processing was likely the dominant language processing style for much of human history, thriving in oral traditions and adapting language to serve its primary purpose: conveying meaning with efficiency and context. It remains a powerful, natural approach to communication, rooted in humanity’s shared linguistic heritage. By contrast, literacy and Analytical Language Processing are relatively recent developments, emerging alongside the rise of written systems and industrialisation. Whilst these approaches have undeniable value, they should not erase or diminish the strengths of GLP, which continues to shape how a significant portion of the population—approximately 40%—processes language.

However, modern systems often frame GLPs as “disabled,” driven by capitalist frameworks that profit from endless remediation schemes. Teaching GLPs within the same classrooms as ALPs, using inclusive practices that honour all language processing styles, would be far more effective—but far less profitable. Instead of recognising GLP as a natural and valid approach, capitalism has built an industry around remediation, extracting profits from interventions and therapies designed to “fix” GLPs rather than support them. My book, Holistic Language Instruction (Lived Places Publishing, 2024), provides a framework for teaching GLPs and ALPs together, integrating diverse language styles into a single classroom environment. This inclusive approach challenges the profit-driven narratives that underpin current education systems, advocating for equitable and effective instruction for all learners.

As we reframe GLP as the historical norm, we must also recognise its enduring relevance. Modern trends like texting, emojis, and memes reflect Zipfian principles of efficiency, demonstrating that GLP continues to inform how humans communicate in context-dependent and minimalist ways. These trends are not anomalies; they are extensions of GLP’s strengths, reminding us that diversity in language processing enriches rather than detracts from communication.

The call to action is clear: we must embrace the value of GLP scripts and Zipfian efficiency, both in historical and modern contexts. Educators and communicators can create more inclusive systems by teaching with the understanding that all language processing styles are valid and that diversity is a strength, not a challenge. By rejecting the commodification of language instruction and instead fostering classrooms that celebrate and support all learners, we can honour the legacy of GLP and ensure its strengths are recognised for generations to come.