The Classroom as User Experience: Teaching with Intention, Not Tradition

How Inclusive Design and Student-Centred Teaching Transform Engagement and Outcomes in K–12 Classrooms

I remember sitting through my district’s 30 hours of Special Education onboarding, listening to the reductive ways autistic students were spoken about. It wasn’t necessarily malicious, but it was profoundly limited—thin descriptions that flattened entire lives and silenced complexity. It was centred in the medical model, ugh. No one seemed curious to dive deep into what autism actually meant beyond compliance and intervention. I didn’t hear anything that reflected my lived experience as an autistic person, let alone my identity as a gestalt language processor. The teacher training curriculum I’d encountered up to that point offered no mirrors for someone like me—no sense that people like us, autistic adults, might stand at the front of a classroom, let alone shape the field of education. Instead, I found only windows that looked out on a world where I felt invisible. That realisation became one of the seeds for No Place for Autism?, where I began to interrogate these blind spots in the system.

At the same time, I was wrestling with what kind of teacher I wanted to be. In my previous life teaching forensic sciences, the structure was entirely teacher-led. For almost 25 years, I stood at the centre of the classroom, orchestrating every moment and holding every answer. That was the expectation, and I was comfortable in it. But K–12 teaching was different—and I was different by this point. I’d come to recognise the limits of teacher-centred spaces, where students are expected to conform to the vision of the person in charge. I didn’t want to replicate that dynamic. More than anything, I wanted to know who my students were, what they cared about, and what they could bring to the table.

It reminded me of a role I had long ago—offensive lineman. In American football, linemen rarely get the spotlight. They’re there to clear the path, to give the skilled players room to run, pass, and shine. That’s how I began to see my role as a teacher: not as the star at the centre but as someone clearing the way for my students to lead. This shift in mindset required rethinking everything, from my autistic urge to info-dump to my old assumptions about what teaching looked like. Paulo Freire’s words became a guiding force for me—education as liberation, not transmission. Freire’s vision of the teacher as guide, mentor, and even protector resonated deeply. I wasn’t there to simply “facilitate” learning in some detached way. My role was to hold the space, clear the obstacles, and build trust so my students could claim their own education.

This shift—from centring myself to centring my students—transformed everything about my practice. It taught me that the deepest learning comes not from what I say, but from the space I create for my students to thrive.

The Teacher-Centred Vision

Many new teachers step into the classroom with a strong, carefully crafted vision of their practice. They’ve dreamed of becoming teachers, of the lessons they’ll deliver, the students they’ll inspire, and the class they’ll lead. It’s a vision that often centres themselves—their teaching style, their expectations, their lesson plans—and it’s easy to understand why. Teaching is deeply personal, and there’s no shortage of media that idealises the “hero teacher” standing at the front of a room, single-handedly changing lives. But for so many of us, especially in Title 1 settings, that vision doesn’t survive day one.

When I first started teaching in 1997, long before I had the words for it, I was acutely aware of my tendency to info-dump—to overwhelm others with details. It’s an urge that’s always present, a cascade of thoughts waiting for the smallest prompt to pour out. But I quickly realised that this approach wouldn’t work in a K–12 classroom. Bombarding students with too much information would only shut them down.

To address this, I began refining my answers, distilling them to what truly mattered. I applied the same approach to planning lessons and units, stripping away anything unnecessary and focusing on clarity and purpose. It became an exercise in restraint—holding back, even when there was so much I wanted to say and do.

At first, this was a struggle. I had moments where I felt unseen, where I wondered if I was giving enough of myself to my students. My instinct was to fill every silence, to provide every answer, as if that was the measure of a “good” teacher. But as time went on, something shifted. I realised that my job wasn’t to be the centre of the room—it was to create a space where my students could step forward. There was a liberating feeling in knowing that I didn’t have to do or say everything. My students could and should take the lead. Their voices, their perspectives, and their questions mattered far more than my perfectly scripted explanations.

This realisation brought me face-to-face with a larger systemic issue: teacher preparation programmes often fail to prioritise student-centred mindsets. New teachers are trained to manage classrooms, deliver content, and assess learning outcomes, but they aren’t always taught how to listen—how to centre their students as full participants in the learning process. Instead, they’re often pushed toward rigid frameworks and pre-set visions that leave little room for flexibility, especially when working with neurodivergent, disabled, or historically underserved students.

What I came to understand is that teaching is not about performing or controlling. It’s about making space—for learning, for growth, for students to be seen and heard. That shift from a teacher-centred vision to a student-centred practice was not easy, but it was necessary. And it started with the humility to step back and recognise that I didn’t need to know everything, and I didn’t need to do everything. My students would show me the rest—if I let them.

Redesigning the ‘User Experience’

When we talk about “user experience” (UX), most people think of retail spaces, websites, or apps—places where every detail is intentionally designed to meet the needs of the user. Oddly, we don’t seem to bring the same care and thoughtfulness to K–12 classrooms, despite the fact that students spend hours of their lives navigating these spaces every day. Classrooms are learning environments, yes, but they are also human environments. The “user experience” of a classroom matters: how students move through the space, how they interact with content, and how the learning process either lifts them up or shuts them down.

I began redesigning my classroom “UX” with a simple formula: design instruction for the student with the most complex IEP accommodations. The idea is straightforward. If I plan my lessons to meet the needs of the student who requires the most support, then the entire classroom becomes more accessible and inclusive. This doesn’t mean sacrificing rigour or lowering expectations. There are still learning targets, and they’re still challenging—but they are achievable with the right scaffolding, supports, and pacing. Most importantly, the “user experience” doesn’t overwhelm.

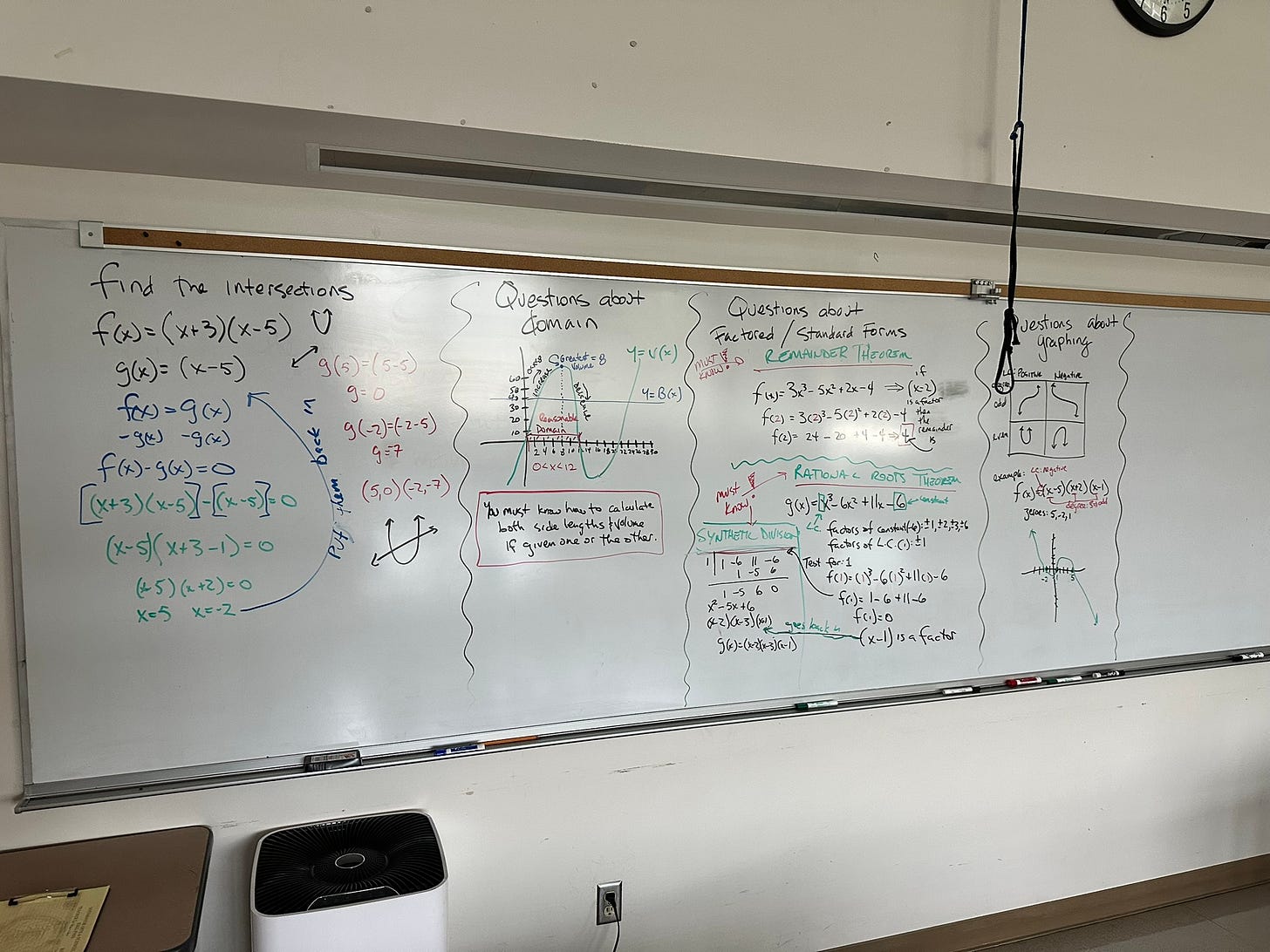

What’s powerful about this approach is that it doesn’t require extra planning time or a co-teacher. It’s a mindset shift that changes how lessons are built from the ground up. At first, when Admin would come through on their instructional rounds, observing my class, they weren’t sure what to make of it. My classroom didn’t look like the others: students moved at their own pace, tasks were heavily scaffolded, and the atmosphere felt collaborative rather than top-down. The whiteboards where filled with heavily diagrammed problems. But the results spoke for themselves.

My students have shown incredible growth. Supporting other teachers in the maths department has led to positive change, too. Last year, Algebra II had the most failures on campus, and all but one student with an IEP failed. This term, as a co-teacher supporting all sections of Algebra II, not a single student with an IEP failed. The only two students who didn’t pass were chronically absent. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles and scaffolding are woven into every part of the curriculum, from the initial lesson to the final assessment. Instruction doesn’t stop being responsive either—students let us know in real time when they’re struggling, and we adjust. (“Dr. H?! Can you translate this into girl maths?!”)

This formula addresses more than just logistical constraints; it reflects a moral imperative for inclusivity. Designing instruction around the needs of one student creates an environment where all students can succeed. It dismantles the idea that accommodations are “extras” or burdens to be grudgingly added later. Instead, they become the foundation for effective, inclusive teaching.

We don’t question whether websites should be accessible to all users. Why do we question whether classrooms should? In rethinking the user experience, we create classrooms where students don’t just learn—they thrive.

Overcoming the Urge to Info-Dump

Early in my time teaching in forensics, long before I had words like “autistic” or “gestalt language processor” to explain my experience, I could feel the energy in the room shift. It was subtle at first—a few glazed-over expressions, the restless tapping of pens, students zoning out. I didn’t know what to call it, but I recognised it for what it was: disengagement. I had been info-dumping again, overwhelmed by the urge to share everything I knew, every detail, every connection. It wasn’t intentional, but I could sense when I had lost the room. I had to stop. I had to summarise, move on, and figure out what my students actually needed.

Years later, after my diagnosis, I began to understand what was happening: my autistic tendency to hyper-focus and overshare was short-circuiting their learning experience. But I also came to realise that my autistic traits—my hyper-empathy and, paradoxically, alexithymia—were my strengths. I learned to navigate the energy in the room, to feel it, even if I couldn’t always name it. I started riding that energy like a current, adjusting my approach in real time to keep my students engaged and connected.

The real shift happened during my years teaching forensic sciences, long before I entered K–12 classrooms. Back then, I learned to focus less on what I wanted to teach and more on what my students needed to learn for their roles, their cases, and the evidence they were handling. The depth and breadth of what I taught was always dictated by the “user experience” of their lives and work.

If I was training brand new latent print analysts, for example, the content couldn’t be heavy on complex maths like Fourier Transforms (FFTs)—it wouldn’t serve them yet. Instead, the focus was practical: image analysis broken down into steps they could immediately apply, combined with how to explain their methods in clear, confident terms at trial. The same was true when I taught mobile device forensics or DVR recovery. The tools and techniques mattered, but so did the ability to translate that technical knowledge into real-world application.

This approach grounded the learning in what was relevant and necessary for them. It was never about showing off what I knew or delivering content for its own sake; it was about ensuring my students could take the knowledge, carry it into their work, and feel prepared for the demands of their jobs. When they saw the connections to their cases, the energy in the room shifted. They leaned in, engaged, and asked sharper questions.

In many ways, this experience shaped how I later approached teaching K–12. The principle was the same: students engage when the learning is relevant and responsive to their needs. In forensics, I had to meet analysts where they were (the volunteer and the ‘voluntold’)—providing practical tools and understanding their real-world challenges. In K–12, it meant connecting lessons to students’ interests, experiences, and aspirations. Whether training forensic analysts or teaching teenagers, the user experience always came first.

This approach aligns closely with Paulo Freire’s principles of dialogue and respect—creating space for students to co-construct knowledge rather than passively receive it. In forensics, I wasn’t there to lecture endlessly or overwhelm them with information. I was there to guide them: to show the path, to help them refine their understanding, and to prepare them for the reality of their work. It was about empowering them to connect what they learned to the evidence they handled and the challenges they’d face in courtrooms and labs.

I’ve carried this same mindset into K–12 classrooms. Students often know far more than they let on, but they need to feel trusted, valued, and seen before they’ll share it. I had to learn to step back and balance my roles carefully—being a guide when they needed direction, a mentor to encourage their growth, and a protector to ensure they felt safe enough to take risks. It’s a delicate balance, but when it’s done right, it creates the conditions for real learning to happen.

Freire believed that education should be liberating, not oppressive—that it should empower students to bring their voices, their knowledge, and their experiences into the room. I came to see my role not as someone who fills their minds with everything I know but as someone who clears the way for them to discover what they know and what they can do with it. Just as I designed forensics lessons around my students’ cases, I now design instruction around my K–12 students’ needs, interests, and strengths.

When their engagement, questions, and perspectives take centre stage, the classroom transforms. They aren’t just learning content; they’re learning to think critically, to ask questions, and to take ownership of their education. That’s when the energy in the room shifts—when learning becomes something they feel they can own rather than something being done to them.

Practical Outcomes of a Student-Centred Approach

The shift to a student-centred approach has brought tangible changes to my classroom, both in engagement and academic progress. A clear example is Algebra II, a subject that previously saw the highest failure rates on campus. Last year, nearly every student with an IEP failed. This term, with a focus on inclusive instruction and UDL, all students with IEPs passed. Most students earned a C or above. When students see themselves reflected in the design of the instruction and feel supported, success becomes achievable.

Beyond grades, this approach has fostered a deeper sense of safety and belonging in the classroom. Students know they can ask for help and will receive it in a way they can understand. I often hear, “Dr. H, can you translate this into girl maths?”—a playful shorthand for scaffolding concepts in ways that make sense to them. This willingness to ask questions, to say when they’re struggling, and to advocate for themselves didn’t happen overnight. It’s the result of building trust and showing students that their voices and learning processes matter.

This foundation of trust also transformed collaboration. You can’t do “purposeful and productive instructional grouping” when students are disconnected and disengaged. But when they feel safe, supported, and confident in their abilities, something shifts. I’ve watched students take the lead in group discussions, explain concepts to their peers, and find creative ways to solve problems together. Independence grows naturally when students realise the classroom is their space, designed with them in mind.

A student-centred approach doesn’t just lead to better academic outcomes; it creates classrooms where students are empowered to learn, belong, and thrive.

Lessons for Educators

For teachers striving to make a similar shift, the most important step is to recognise and challenge the teacher-centred mindset. Many of us enter the profession with a vision of what our classroom will look like—what we will do and say, how we will teach. But real learning begins when we shift the focus to our students: their unique needs, experiences, and strengths.

Start with one student. If you have a student with a complex IEP, design your instruction around supporting them. Meet their needs with intentional scaffolding, accessibility, and clarity. The beauty of this approach is that it doesn’t just help that one student—it creates an inclusive environment that benefits everyone. That mindset shift ripples outward. Suddenly, all students are receiving instruction that doesn’t overwhelm, that challenges them appropriately, and that acknowledges their right to belong in the classroom.

This isn’t about compliance or accommodations tacked on as an afterthought. Designing with inclusivity first ensures that no student is left behind. It’s also a moral imperative, especially in Title 1 schools where resources are limited, and systemic inequities weigh heavily. My experience proves that this can be done without expensive tech, flashy programmes, or specialised charters. In fact, the approach outlined in Harvard Ed Magazine—focused on expensive tech tools or segregated charter models—misses the point. Inclusion isn’t a luxury or a premium product; it’s a mindset shift that any teacher, in any classroom, can embrace.

In a Title 1 setting, we don’t all have co-teachers or pricey intervention systems to lean on. But what we do have is the power to rethink our practice. When we centre students—when we build trust, scaffold intentionally, and design the “user experience” with their needs in mind—remarkable things happen. I’ve seen the impact firsthand: fewer failures, amazing growth, deeper engagement, and classrooms where students feel seen, supported, and empowered.

Inclusivity isn’t an add-on, and it doesn’t require an influx of resources or technology. It requires teachers who are willing to rethink their role, shift their mindset, and meet students where they are. Start small, start with one student, and let it grow from there.

Final thoughts …

When I reflect on my teaching journey, I see how far I’ve come—from those early days of info-dumping and overwhelming my students to facilitating learning experiences that are meaningful and responsive. This growth, in many ways, flies in the face of stereotypes about autistic people. We’re often written off as incapable of self-reflection, adaptation, or growth. But here I am, a teacher who has learned to listen, to adjust, and to build a classroom where students are at the centre.

I’ve let go of the rigid vision I once held of what a classroom “should” look like. My focus now is on creating spaces that reflect the needs of the students who inhabit them. It’s about trusting their voices, respecting their experiences, and designing instruction that feels accessible and empowering. A student-centred approach isn’t about lowering expectations or losing control—it’s about rethinking control altogether and fostering an environment where students can truly thrive.

This is the work of every educator. We must design the “user experience” of our classrooms with students in mind, not as an afterthought but as the foundation of our practice. When we centre inclusivity and accessibility, we build spaces that not only support learning but protect and uplift all learners.

The truth is, inclusion doesn’t require perfection, expensive tools, or unlimited resources. It requires intention. It requires teachers who are willing to challenge old assumptions, to start small, and to grow alongside their students. If I’ve learned one thing, it’s this: when you design for the student with the most complex needs, you create a space where everyone belongs.

So, here’s the call to action: let’s centre our students. Let’s create classrooms that see them, support them, and clear the way for them to shine. That’s how we transform education—not with quick fixes, but with the belief that every student deserves a space to learn and to be seen.