Rethinking Rigor: Creating Autistic-Friendly Deep Learning Spaces

A Personal and Professional Lens on Rigor and Inclusion

Growing up as an autistic Gestalt Language Processor (GLP), I learned language in a way that made no sense to those around me. Whilst most children are expected to acquire language naturally, I didn’t piece together individual words into sentences. Instead, I absorbed scripts—gestalts—borrowed from the world around me. My first language wasn’t English, or even what anyone would call a conventional language; it was an intricate mosaic of phrases and intonations lifted from my Canadian-Scottish grandmother’s daily speech, her choice of television shows from the BBC, and a collection of conversational elements from the people I encountered in my day. To the outside world, these utterances must have seemed random and nonsensical. But to me, they were the building blocks of my understanding, my way of making sense of a world that often felt overwhelming.

Language has always been a challenge. Even now, as an adult and a teacher, functional language can feel like a tightrope I’m walking—always balancing between what I mean to say and how others interpret it. I’m a “Level 2 autistic person,” meaning I require significant support with day-to-day communication. As a GLP, I don’t just “learn” language in the traditional sense; I live it in chunks, patterns, and echoes, often struggling to connect these fragments in ways that meet the expectations of neurotypical communication.

This struggle shaped how I experienced education. As a Long-Term English Learner (LTEL), I encountered barriers at every turn, many of which were hidden under the guise of “rigor.” For me, rigor often meant an artificial difficulty layered onto tasks—designed not to promote learning or critical thinking, but to weed out students like me. High-stakes tests, fast-paced lessons, and rigid benchmarks weren’t just academic hurdles; they were messages that said, “There’s no place for autism here.”

As a student, rigor felt like gatekeeping—an arbitrary narrowing of who could belong. Now, as a teacher, I see the same patterns playing out in my professional life. Too often, rigor isn’t about fostering deep learning or meaningful engagement. It’s about exclusion: making the path so narrow and the stakes so high that only a select few can pass. For autistic students, particularly those who process language and information differently, traditional rigor becomes a barrier that’s almost impossible to overcome.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Rigor and accessibility are not opposites. In fact, I believe that lowering the affective filter—the emotional and psychological barriers to learning—is the most powerful way to create an environment where true rigor can thrive. By fostering curiosity, emotional safety, and inclusion, we can redefine rigor as a tool for empowerment rather than exclusion.

Today’s article explores the disconnect between traditional notions of rigor and the needs of students like me—autistic, GLP, LTEL, and beyond. It proposes a new vision for rigor, one that values accessibility, curiosity, and meaningful engagement over arbitrary difficulty. Because when we redefine rigor, we open doors instead of closing them. And that’s a world where everyone—autistic, neurodivergent, or otherwise—can thrive.

The Incompatibility of Traditional Rigor and Lowering the Affective Filter

Traditional notions of rigor—characterised by high-stakes testing, fast-paced lessons, and strict benchmarks—often amplify anxiety in students, particularly those who are autistic or LTELs. For autistic students, the pressure to perform in environments designed around the processing styles of the neuro-majority creates significant barriers to engagement. High-stakes exams, for instance, not only demand rapid recall of information but often require students to demonstrate their knowledge in rigid formats that leave no room for alternative ways of thinking. For LTELs, this anxiety is compounded by the additional challenge of navigating complex language demands, often in a language that still feels unfamiliar or inaccessible. Together, these factors raise what Stephen Krashen famously termed the “affective filter”—a barrier of stress, self-doubt, and fear that can block meaningful learning.

I experienced these barriers firsthand. As an autistic student and LTEL, I often found myself overwhelmed by the sheer pace and intensity of lessons that allowed little time for processing or reflection. Instructions felt like a flood of words that I struggled to assemble into coherent meaning, whilst assessments seemed more like tests of how well I could mask my confusion rather than actual measures of understanding. The anxiety of these experiences often left me paralysed, unable to focus on the material because my energy was consumed by trying to survive the environment itself. I’ve documented some of these experiences here as I’ve progressed on my journey as a teacher. The affective filter in these moments wasn’t just a metaphor—it was a wall I couldn’t climb, one that made me feel like I didn’t belong in the classroom at all.

This fixation on rigorous outcomes often prioritises the end product over the process of learning. For autistic students, particularly those who are GLPs, this focus disregards the unique ways we engage with and make sense of the world. GLPs like me don’t necessarily build understanding step by step; instead, we absorb and use chunks of language, scripts, and patterns that are meaningful to us. These may seem unconventional or even nonsensical to an outside observer, but they represent real, valid ways of processing and learning. Traditional rigor rarely accounts for this, instead forcing students to conform to narrow expectations that undervalue diverse ways of thinking.

In my teaching practice, I’ve seen the power of shifting focus from the product to the process. For one student, this meant letting her use a mix of English and Spanish to write a maths explanation, recognising that her bilingual thinking was a strength, not a weakness. For another, it meant valuing her ability to create visual representations of concepts when traditional written explanations weren’t accessible. In both cases, by prioritising the journey of learning over rigid outputs, I saw students engage more deeply with the material and develop confidence in their abilities.

These moments reaffirm my belief that rigor, as traditionally defined, often excludes rather than includes. It’s a system that tells students like me—and those I now teach—that we don’t belong. But when we reframe rigor to honour diverse processes and reduce anxiety, we create spaces where all students can thrive, not in spite of their differences but because of them.

Yet, in many classrooms, rigor is paired with an expectation for students to juggle multiple demands at once—listening to instructions, recalling prior knowledge, synthesising new information, and completing tasks, often under tight time constraints. For students with executive functioning challenges, including many autistic students, GLPs, ADHD, etc., this approach is quite overwhelming. The rapid transitions and multitasking required in such environments don’t just create additional stress; they effectively shut down the student’s ability to engage meaningfully. Instead of focusing on the content, students are left grappling with how to keep up with the relentless pace.

For GLPs, whose brains naturally process information in wholes rather than in linear, step-by-step sequences, this style of instruction can be particularly disabling. The demand to switch contexts quickly, break down tasks into discrete parts, and manage competing priorities runs counter to how GLPs process and apply their understanding. I’ve seen students in these situations freeze, overwhelmed by the sheer number of steps required to complete a task before they’ve even had the chance to orient themselves. It’s not a lack of intelligence or ability—it’s an environment that’s set up in a way that works against their natural strengths.

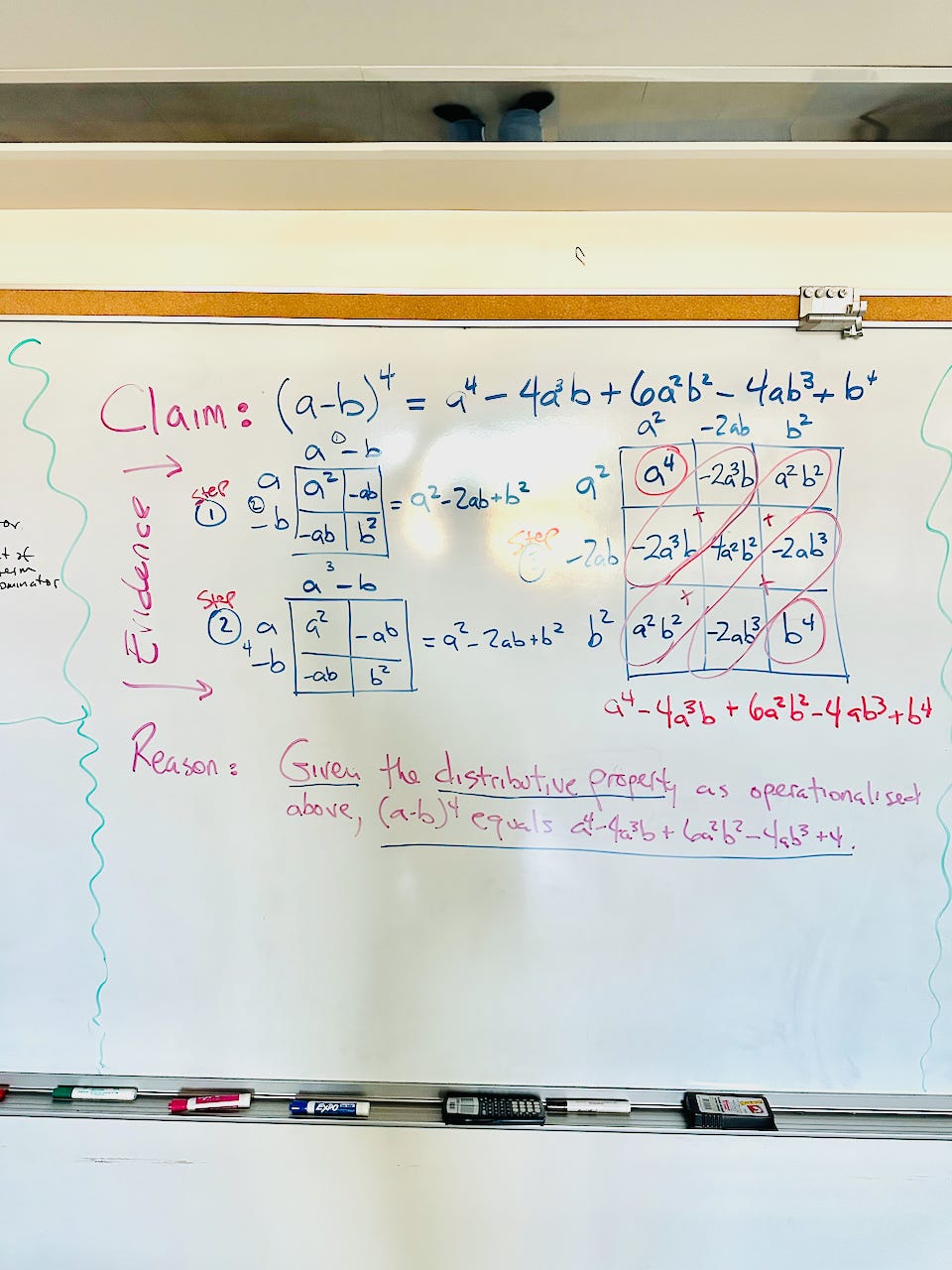

In my classroom, I’ve found that focused, step-by-step approaches can alleviate much of this burden (see the images below). Instead of overwhelming students with the entire scope of a task, I break it down into manageable parts, providing visual aids, sentence frames, or partially completed examples to guide them through the process - including the necessary formulae. For example, when teaching polynomial identities, I use the Box Method to visually structure the steps, allowing students to see how each part builds on the last (second image below). This not only reduces cognitive load but also gives students the confidence to tackle each step without becoming overwhelmed by the whole.

I also rely heavily on structured techniques like Self-Directed Strategy Development (SRSD) to support executive functioning. SRSD provides students with clear, consistent routines for approaching tasks, which helps minimise the mental effort required to figure out how to start. For a student writing a mathematical proof using the Claim-Evidence-Reason (CER) model, for example, SRSD offers a template to organise their thoughts, a checklist to guide their work, and explicit modelling to show them what success looks like. By removing the guesswork and providing a predictable structure, these strategies create a sense of safety and reduce the barriers that often accompany rigorous tasks.

When students have the support they need to focus on one step at a time, their engagement transforms. I’ve seen students who initially shut down in response to a challenging problem gain the confidence to persist when given a scaffolded approach. These techniques don’t just make the material accessible—they create an environment where students can take ownership of their learning. For GLPs in particular, this approach honours their natural processing style, allowing them to connect the parts into a cohesive whole at their own pace. In this way, the process becomes empowering, and the learning becomes meaningful.

Reframing Rigor

Rigor is often equated with covering as much material as possible, a race through a curriculum checklist that leaves little room for exploration or reflection. Yet true rigor, in my experience, is not about breadth but depth—allowing students to engage meaningfully with fewer topics rather than skimming the surface of many. Depth creates opportunities for connection and mastery, especially for students who thrive in environments that value process and exploration over speed and output.

One of the most profound teaching moments I’ve experienced came when I chose to slow down and focus on a single topic: polynomial identities. Rather than rushing through a checklist of algebraic skills, I devoted several lessons to guiding my students in understanding and proving just one identity using the CER framework. By giving them the time and space to deeply explore the topic, I saw their confidence and understanding flourish. They began to make connections between the patterns in polynomial structures and the mathematical principles we’d been discussing. More importantly, they could articulate those connections in ways that felt meaningful to them. What started as a seemingly narrow focus led to a broader understanding that extended beyond that single unit, showing me that rigor rooted in depth has far greater impact than surface-level speed.

Rigor also means meeting each student where they are, providing challenges that are appropriately scaffolded to their individual needs. For autistic and LTEL students, this can look very different from the traditional image of rigor. One student in my classroom, for instance, was overwhelmed by the dense language of word problems in Algebra II. Rather than pushing her to tackle them head-on, I broke the problems into smaller chunks and provided bilingual sentence frames to support her language processing. This allowed her to focus on the mathematical reasoning without getting lost in the linguistic complexity. Another student, a GLP, struggled with the abstract nature of proving identities. For him, I created a visual approach using colour-coded grids and hands-on algebra tiles, which transformed what had felt like an inaccessible task into something tangible and manageable (I also mapped out a whole problem on the white board-see above- so he could see the bigger picture. By tailoring challenges to each student’s needs, I’ve found that rigor becomes an achievable and empowering experience rather than an insurmountable barrier.

Perhaps most importantly, rigor should be student-centred, aligning with students’ interests, strengths, and processing styles. When students see themselves reflected in their learning, engagement becomes genuine, and rigor takes on a new dimension (the windows and mirrors approach). For my class of bilingual and neurodivergent learners, this has meant incorporating culturally relevant examples, such as exploring algebra’s roots in Arabic and Mesoamerican mathematics. These connections not only validate my students’ identities but also spark their curiosity, leading to deeper engagement. I’ve also allowed students to create their own polynomial identity problems, encouraging them to explore concepts in ways that felt personally meaningful. One student crafted an example involving patterns from her favourite video game, whilst another related polynomial identities to the symmetry of designs she’d seen in her family’s traditional embroidery.

These moments demonstrate that rigor doesn’t have to be about arbitrary difficulty or rigid benchmarks. It can—and should—be about creating spaces where students can explore, connect, and grow in ways that honour their individuality. True rigor is not about forcing every student into the same mould but about recognising the value of their unique contributions and supporting their journey to mastery. When we reframe rigor to focus on depth, individualisation, and student-centred learning, it becomes a tool for inclusion rather than exclusion.

How Lowering the Affective Filter Enhances Rigor

Lowering the affective filter is often misunderstood as making things easier or less rigorous, but in reality, it enhances students’ capacity for intellectual risk-taking. When students feel emotionally safe, they are more willing to step outside their comfort zones, attempt new challenges, and engage deeply with their learning. In my classroom, this manifests as students raising their hands to share their reasoning, even when they’re unsure if they’re right. I see it when a student, initially hesitant, approaches a challenging polynomial problem with curiosity instead of fear because they know mistakes are part of the learning process, not something to be punished or shamed. By fostering an environment where questions are celebrated and misunderstandings are opportunities for growth, I’ve witnessed my students take ownership of their learning in ways that were previously unthinkable.

For many of my students, particularly those who have experienced repeated failure in traditional settings, this kind of emotional safety is critical for building persistence. A high affective filter can make even small setbacks feel like insurmountable barriers, leading students to shut down or disengage. In contrast, a low-affective-filter environment creates the conditions for perseverance. One of my students, an autistic GLP who struggles with transitions, initially avoided anything that felt new or uncertain. By breaking down tasks into predictable, manageable steps and celebrating every small success, I saw his persistence grow. He began to approach problems with determination, revisiting them even after making mistakes, because he knew he had the support and tools to try again.

Persistence in my classroom often looks like students returning to a problem they initially found overwhelming, equipped with a new strategy or perspective. For example, a bilingual student working on a CER explanation for a polynomial identity might use bilingual sentence frames and graphic organisers to clarify her thinking. When she encounters a barrier, she doesn’t give up but instead uses the scaffolds provided to try a different approach. This kind of persistence is not innate—it’s nurtured through a supportive environment that encourages students to see challenges as opportunities rather than threats.

Lowering the affective filter also challenges the pervasive myth that accessible learning means “dumbing down” content. Accessibility isn’t about reducing the complexity of the material; it’s about providing students with the tools, supports, and pathways they need to master it. In my classroom, this means using multimodal instruction to make abstract concepts tangible and understandable. For instance, when teaching polynomial identities, I incorporate hands-on activities like algebra tiles, visual aids like the “Box Method,” and sentence frames for both written and oral reasoning. These supports don’t simplify the content—they make it approachable, enabling students to engage with rigorous material in ways that align with their strengths and needs.

Culturally responsive teaching also plays a key role in making rigor accessible. When my students see their identities and experiences reflected in the curriculum, they are more motivated to engage deeply with the material. One student who initially dismissed algebra as irrelevant became captivated by the historical contributions of Arabic mathematicians when we explored their role in developing foundational concepts. This connection not only sparked her curiosity but also inspired her to approach the subject with a newfound sense of purpose.

By lowering the affective filter, we create environments where students feel empowered to take risks, persist through challenges, and achieve mastery. True rigor doesn’t come from making learning harder for its own sake; it comes from ensuring that every student has the opportunity to succeed, regardless of their starting point. When students feel supported and valued, they rise to the challenge—not in spite of the scaffolds provided but because of them.

A New Vision for Rigor

Rigor should not be a test of endurance or a gatekeeping mechanism; instead, it should empower students to take on meaningful challenges with the tools, support, and confidence they need to succeed. Empowerment in my classroom begins with creating an environment where students feel capable of achieving their goals, regardless of the obstacles they face. This often means blending high expectations with emotional and practical scaffolds, ensuring that students can approach rigorous material without feeling overwhelmed. For example, peer collaboration is a powerful tool I use to foster empowerment. When students work together, they share ideas, build on each other’s strengths, and realise that they don’t have to tackle challenges alone. I also use supportive feedback that focuses on growth rather than perfection, celebrating students’ efforts and progress while guiding them toward improvement. When students know they are supported, they are more likely to embrace challenges and see rigor not as a threat but as an opportunity for growth (a rather ‘matristic’ mindset).

Curiosity-driven learning is another cornerstone of rigor in my classroom. Fostering curiosity isn’t just about making lessons interesting—it’s a rigorous act that requires students to think critically, explore deeply, and engage independently with the material. Curiosity invites students to ask their own questions and seek their own answers, moving beyond rote learning to genuine inquiry. One example of this in my teaching is a project where students created their own polynomial identity problems, drawing inspiration from their interests and experiences. One student related polynomial symmetry to traditional embroidery patterns, whilst another used video game design to explain real-world applications of algebra. These projects didn’t just engage students—they required them to think deeply about the concepts, apply them creatively, and communicate their understanding in ways that felt meaningful to them. By prioritising curiosity, we make rigor personal and relevant, ensuring that students are invested in their learning because it connects to their lives and passions.

True rigor also honours diversity, embracing the many ways students think, learn, and demonstrate understanding. Accessibility and inclusion are not barriers to rigor; they are its foundation. As an autistic GLP and LTEL, I know firsthand how traditional notions of rigor can exclude students whose strengths and needs don’t align with neurotypical or monolingual expectations. For me, language has always been a challenge—not because I lacked intelligence or curiosity, but because my way of acquiring and processing it didn’t fit the conventional mould. This lived experience has shaped my approach to teaching and my belief that rigor must be accessible to all.

In my classroom, inclusive rigor means providing multiple pathways to success, recognising that not all students will approach learning in the same way. For my bilingual students, this might involve allowing them to use both English and their home language to articulate their reasoning. For my GLP students, it means using visual supports, sentence frames, or even scripts to scaffold their communication. These supports don’t diminish the rigor of the task; they simply ensure that every student has the opportunity to engage with it fully.

Inclusive rigor also involves validating students’ identities and experiences. By incorporating culturally responsive teaching, I create lessons that reflect the diversity of my students and invite them to bring their whole selves into the classroom. For example, when teaching algebra, I include the contributions of Arabic and Mesoamerican mathematicians, helping students see their heritage reflected in the material. This not only makes the content more engaging but also reinforces the idea that their identities are assets, not barriers, to learning.

Rigor as empowerment, curiosity, and inclusion transforms the classroom into a space where all students can thrive. It shifts the focus from arbitrary difficulty to meaningful challenge, from exclusion to belonging. When rigor is redefined in this way, it no longer asks, “Who can survive?” Instead, it asks, “How can we ensure everyone succeeds?” This vision of rigor isn’t just about teaching content—it’s about teaching students that they are capable, valued, and integral to the learning process. That’s the kind of rigor that changes lives.

Moving Forward: Rethinking Rigor in Education

Moving forward, rethinking rigor requires a shift from traditional definitions of difficulty to a focus on emotional safety, accessibility, and meaningful engagement. For educators and policymakers, this means taking concrete steps to support classrooms where all students—not just ones from the neuro-majority—can thrive. Professional development is a good place to start. Training sessions should help educators understand the importance of lowering the affective filter and incorporating neurodiversity-informed practices into lesson design. These sessions should celebrate, not pathologise, neurodivergent traits like hyper-focus, and explore how they can be harnessed to deepen learning for all students. Imagine a world where “off-topic obsessions” are reframed as pathways to expertise rather than distractions to be managed.

In my classroom, I try to create an atmosphere that invites students into their own flow states—spaces where they can fully immerse themselves in learning without the external pressures of time or performance. Whilst not all of my students are autistic or experience time as fluidly as I do, I know that everyone benefits from being allowed to focus deeply on something that engages them. For me, time melts away when I’m in the middle of designing a lesson or diving into a niche area of research, like the intricacies of GLP language acquisition. It’s not that I lose track of time—it’s that the boundaries of time no longer matter because the work itself becomes all-encompassing.

I want my students to feel that same freedom in my classroom. To do this, I structure lessons in ways that balance predictability and openness. I use techniques like scaffolding to ensure students feel secure enough to take risks, and I build in moments where they can explore their interests within the content. This might mean letting a student spend an entire class period creating a visual proof of a polynomial identity instead of rushing to complete three different problems. It could mean letting another write a CER explanation in their home language before translating it into English. The goal is to provide the tools and space for students to get lost in their learning in the best possible way.

Ultimately, rigor should feel less like a wall to climb and more like an open horizon to explore. By prioritising emotional safety, accessibility, and curiosity, we can transform classrooms into places where students aren’t racing against the clock or conforming to rigid benchmarks but are instead discovering the joy of learning for its own sake. That’s the kind of rigor I want to see—not the kind that says, “You must do it this way,” but the kind that says, “Let’s see how far you can go.”

Final thoughts …

One of the most rewarding moments in my teaching career came when a student, a bilingual autistic girl who had struggled with traditional notions of rigor, finally found her footing. She often avoided tasks that felt overwhelming, especially those with rigid time limits or abstract instructions. The anxiety these created raised her affective filter so high that even starting a task felt impossible. When we began working on polynomial identities, I introduced the “Box Method” and CER explanations in a scaffolded way, allowing her to take things step by step. I encouraged her to use both Spanish and English in her reasoning, assuring her that blending languages was a strength, not a deficit.

Slowly, the walls came down. With each small success, her confidence grew. By the end of the unit, she wasn’t just completing problems—she was explaining them to her peers. I’ll never forget the pride in her voice as she presented her CER explanation to the class, switching seamlessly between languages to articulate her reasoning. It wasn’t that the work was easier; it was that she’d been given the tools, the time, and the emotional safety to engage with it fully. For her, and for so many students, lowering the affective filter didn’t lower the rigor—it transformed it.

Rigor and accessibility are not opposites. When we redefine rigor to centre on inclusivity and emotional safety, we create spaces where every student can engage deeply and meaningfully. These practices aren’t just “nice to have”—they’re essential if we are to make education equitable and empowering for all.

This challenge isn’t just for teachers. Every education stakeholder—parents, administrators, policymakers, and students—must demand affirming practices that prioritise accessibility and curiosity in every setting. Imagine classrooms where students feel seen and valued, where they’re invited to bring their whole selves to the learning process. If we want a future where education serves all students, we must start by redefining rigor. The change begins not with policies or mandates but with a shared commitment to meeting students where they are and showing them just how far they can go.