Only from the Heights of Theory: On the Crumbs of Reform, the Poison of Power, and the Climb Still Ahead

What Lenin’s critique, a Soviet poster, and the gutting of public institutions teach us about surviving a regime that rewrites the future in real time.

A reflection on Lenin, literacy, and late-blooming clarity—from a trans, autistic lens. On theory as survival, memory as resistance, and the climb we make together, one rung at a time. The horizon isn’t gone. Just hidden.

Introduction: The Tower of Theory

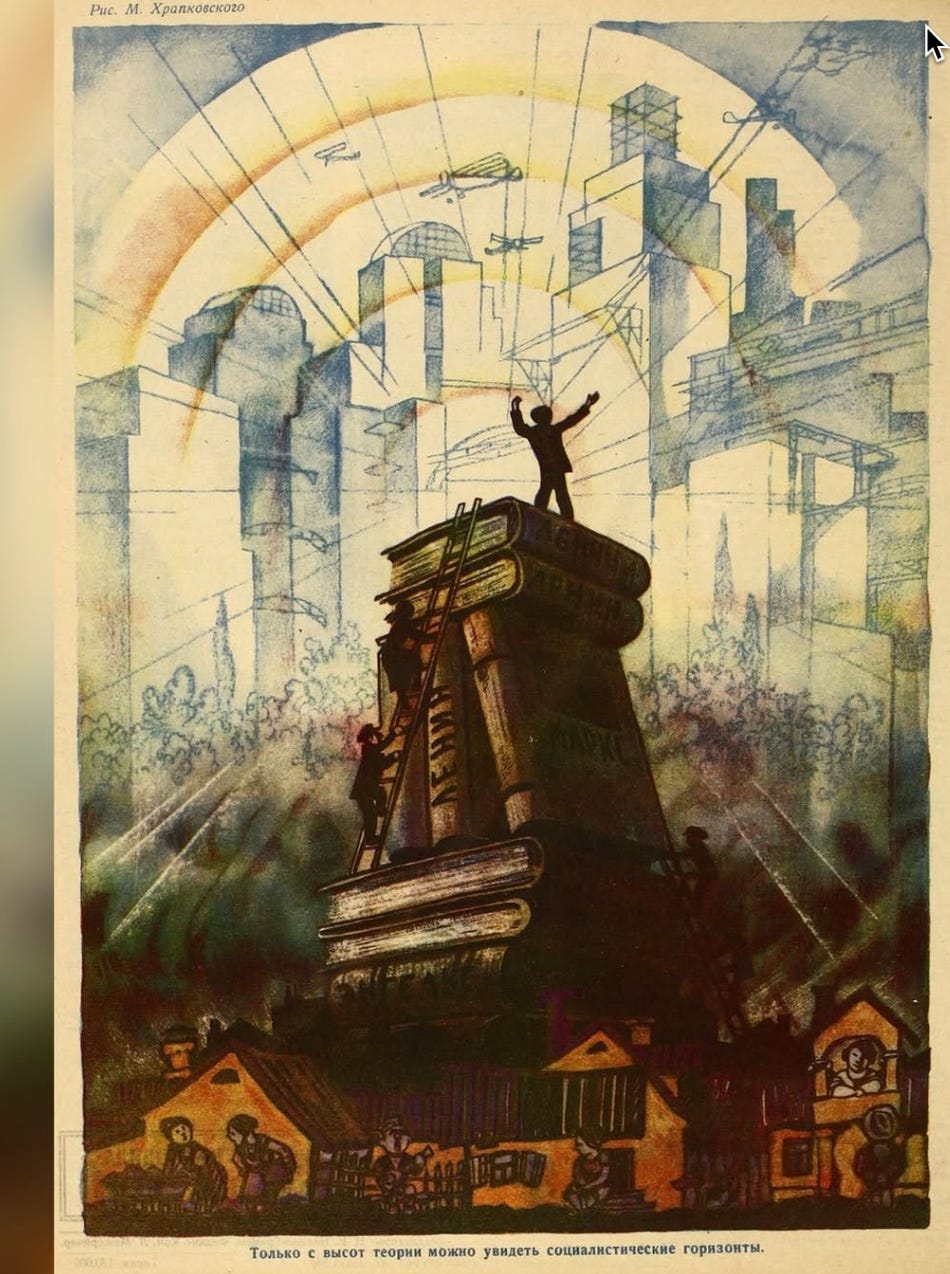

It wasn’t a meme. No punchline. No string of hashtags or overlaid snark. Just an old Soviet poster, maybe eighty, ninety years old. Stark. Elegant. A figure standing atop a tower of books—a spine marked Ленин, Lenin—arms raised toward a radiant, mechanised future. Planes arc overhead. Cities rise. Beams of light trace out possibility. Below, the village scene: warm but shadowed, encased in fences, bound to subsistence. And the words beneath it all, in a line so sharp it pierced something deep: “Only from the heights of theory can one see the horizons of socialism.”

I didn’t just see the image. I felt it. Not in the fragile sense people often ascribe to being “triggered,” but in the more accurate, autistic, circuit-breaker sense—an interruption, a redirection, a forced clarity. Something that snaps the system out of a locked loop. Because I’d been looping. Watching, lately, as everything—public health, education, housing, care—gets stripped for parts. As cuts become closures, and closures become normal. As the “Big Beautiful Bill” rolls in like a wrecking ball gilded in flag decals.

The image called something back into alignment. That sense I’ve had since childhood, before the words arrived—when I could only speak in pictures, echoes, associations. This is why imagery speaks so clearly to the gestalt-processing mind. It holds everything at once. Not in sequence, but in structure. Not linearly, but relationally. I didn’t need the poster to explain. It showed. It gestured. And I recognised the gesture.

Theory, it seemed to say, isn’t academic in the pejorative sense. It’s not distance. It’s elevation. It’s the only way to see the machine that’s grinding us down. Without it, we are trapped in the valley—close to the gears, but blind to the structure. That’s how it feels, watching the world’s care systems unravel whilst being told to “vote harder.” Like kneeling in a smoke-filled room, trying to read a map that’s already been set alight.

Lenin understood this. Theory, for him, wasn’t indulgent—it was essential. Praxis without theory is blindness. The poster doesn’t show heroes or geniuses. It shows people climbing, together, step by step. Not flying. Not falling. Climbing—on books, no less. It isn’t utopia. It’s a blueprint. And it starts with seeing.

The Material Base is Not Enough

The people below the tower in the poster—those in the cottages, among the smokestacks, faces turned downward—aren’t depicted as idle or ignorant. They’re busy. Bent over tasks. Children in laps, tools in hand. They are preoccupied with survival. That, too, is familiar. It’s the reality for so many of us now—those juggling multiple jobs whilst navigating collapsing safety nets, rationing insulin, skipping meals so children can eat, filling out forms for aid that might vanish with the next fiscal cycle. Not because they’ve failed. Because the system is engineered to keep them low to the ground, eyes level with the dust.

Lenin wrote plainly that giving peasants land, without revolutionising the conditions of ownership and without arming them with political consciousness, doesn’t liberate. It relocates the struggle. The peasant becomes a smallholder—precarious, isolated, endlessly beholden to forces just beyond reach. Re-anchored, not unshackled. We see this echoed now in the language of modern policy: “access” rather than “rights,” “incentives” instead of guarantees, work requirements as the new gatekeeper of health. A SNAP card can be revoked for missing a shift. A prescription unfilled if a form isn’t processed in time. Redistribution becomes a retreat. Something to be clawed back, not built upon. A piecemeal concession in place of a structural reimagining.

But the thing about history is that it leaves traces. Waypoints. Our ancestors and intellectual forebears didn’t only fight—they wrote. They theorised. They etched out maps so we wouldn’t be left wandering. The material conditions alone will not lift us—especially not now, when even those conditions are being razed. But if we can return to the texts, the struggles, the speeches, the pamphlets—if we can climb the stack of books as those figures do in the poster—we might yet find our way.

That’s what makes the image so haunting. Not just its beauty, but its insistence: you are not the first to stand in this dark. Others came before. They didn’t escape by luck or chance. They escaped—when they could—because they saw the structure. Because they had theory. And because they shared it. It’s there. Still waiting. Not as salvation. But as direction. A way home.

What the Horizon Reveals

The city in the poster—bright with spires and bridges and streaming light—is not abstract. It’s not some pastel utopia conjured by sentiment. It’s engineered. Drawn with intention. The beams of light, the flight paths of aeroplanes, the contours of the buildings—they converge with geometric purpose. This is not a fantasy. It’s a horizon mapped by theory. It does not promise ease. But it does promise direction. It offers a vision where public infrastructure belongs to the people, where knowledge builds elevation, and where the future is not random, but constructed.

This is where the contrast with the present becomes almost unbearable.

In the United States, there is no real horizon—no map, no city rising in the distance. What passes for vision is collapse on repeat, dressed up in curated nostalgia and sold like an aspirational lifestyle. The right offers not a future, but the aesthetics of empire—gold trim, martial poses, and the soft-focus fantasy of the “Trad Wife” swaying in a sundress, baking pies in a home that sits atop the ruins of collective care. It is a dream stitched together from sitcoms and state violence, where strength means subjugation and simplicity means silence.

And the Democrats? They are no vanguard, no counterforce. They are a private club for capital, a consultancy firm in party drag, fluent in the language of inclusion but fluent, too, in drone strikes and debt ceilings. They gesture toward compassion whilst scripting legislation that ensures the opposite. They do not interrupt genocide—they smooth its process. Their alliances lie not with the people, but with asset managers and technocrats. Theory, for them, is dangerous—not because it’s radical, but because it’s clarifying. It names the structure they are paid to obscure. It threatens to make visible what they depend on keeping unseen.

What we’re left with, then, is a population caught in the crossfire between two wings of capital—one nakedly revanchist, the other cloaked in virtue-signalling and hollow proceduralism. Neither offers a horizon. Neither shows the city. At best, they rotate the stage props. A debt pause here. A pride flag there. Meanwhile, everything essential—housing, health, education, food—becomes subscription-based, gated, rationed by algorithm. The future is not planned. It is privatised.

This is precisely what Lenin warned about—not just in his agrarian programme, but across his body of work. That reform, without rupture, serves the ruling class. That where there is no theory, there can be no strategy. And where there is no strategy, only the machinery of exploitation will persist.

What the poster shows us—and what we are aching to recover—is the idea that a future can be drawn in advance. Not dictated, but designed. Not decreed, but developed. Through study. Through structure. Through collective will. That the city of light isn’t a daydream. It’s a destination—but only if you know where you’re going. Only if someone builds the ladder. Only if the books are read, the maps consulted, the plans drafted together.

And so we are here, suspended in the absence. The absence of a true vanguard. The absence of oppositional governance. The absence of a party tethered to liberation instead of capital. It is a brutal place to stand. But the poster reminds us: we are not standing still. We are capable of climbing. And those who climbed before us left blueprints behind. Theory is not the city. But it is how we find our footing on the way there.

On Climbing Together

No one in the poster is flying. No one is levitating by force of will or pulled skyward by divine right. They are climbing—together. One hand on a rung, the other helping someone else up. The books form the base. The ladders provide structure. The movement is slow, deliberate, collective. No one is being left behind because no one is ascending alone. This is not heroism as capitalism imagines it—solitary, exceptional, untouchable. It’s study, struggle, solidarity. It’s the long work of climbing with others, not despite them.

Compare that to the stories we’re fed now—the bootstrap parables and startup myths. Under capitalism, success is always personal, and so is failure. Didn’t make it? Must be your fault. Must mean you didn’t want it enough, didn’t hustle hard enough, didn’t grind. These are the fables of meritocracy, sold to us by figures like Ayn Rand, Ronald Reagan, and Margaret Thatcher. But what they called “individualism” was never freedom. It was abandonment repackaged as virtue. It was trauma reframed as tenacity.

Hyper-individualism isn’t strength. It’s a survival response—born of being let down, over and over, by people, by systems, by the very institutions that promised care. It’s what you build when the scaffolding is gone and the floor’s been pulled out. It’s the shell you live in when everything communal has been stripped for profit. No one grows up wanting to go it alone. We’re wired for interdependence. But when every attempt at connection is met with erasure or extraction, isolation starts to look like safety.

The poster rejects that. It shows people climbing, not competing. Climbing, not clawing. And it says clearly: there is no ascent without theory, and no theory without each other. If we’re going to get anywhere, it won’t be by “winning.” It will be by lifting.

The “Big Beautiful Bill” and the Poison Pill of Power

The “Big Beautiful Bill” is a monument to spectacle—rhetorically draped in populist flair, but architecturally hollowed out by cruelty. Its surface language appeals to the working class, the forgotten American, the ordinary taxpayer. It promises sovereignty, accountability, and efficiency. But peel back even a single layer and you find not policy, but sabotage. Buried within is a poison pill—a provision that strips funding from the judiciary for enforcement actions. No money for stays, no support for injunctions, no resources for contempt proceedings. Effectively, it renders legal resistance inert. It’s not merely deregulation—it is the removal of brakes from a vehicle already aimed at the most vulnerable.

When the state defunds the courts’ ability to enforce protections, it doesn’t just alter the law—it collapses the very architecture of contestation. Rights remain on paper, but they become decorative—unfunded, unenforceable, meaningless. The public is left with the illusion of legality, whilst the regime operates with impunity.

Who wins? The same coalition that always wins in a crisis orchestrated from the top: landlords, hedge funds, private equity, religious fundamentalists, carceral state actors, and corporate monopolies. Those who see any check on their power—not as democratic process, but as interference. Those who benefit when regulation is gutted and oversight is absent. Those who profit from instability, because instability forces people into bad deals, exploitative contracts, desperation economies.

Who loses? The rest of us. Disabled people, renters, trans people, migrants, the chronically ill, poor mothers, people in rural medical deserts. Workers whose employers steal wages and now face no real legal consequence. Families evicted without recourse. Patients denied life-saving care. Communities poisoned, and then silenced. Entire classes of people who will experience state abandonment not as policy, but as ambient daily reality.

And who will be destroyed? The ones who have no buffer—no savings, no mobility, no media presence. The ones whose rights have always been tenuous. This bill does not fail to protect them. It designs their precarity on purpose. It facilitates it. It monetises it. It feeds a machine that requires their suffering to function.

The backers of this bill—those in power and those who cheer it on—do not misunderstand its effects. They do not believe the collateral damage is unfortunate but necessary. They want this outcome. Because they believe in a world where the market is God, where power should not be diluted by empathy, and where order is enforced not through care, but through hierarchy, extraction, and control.

When the state denies the judiciary its oxygen, it doesn’t just rewrite the law—it erases the very possibility of contesting it. That is the true aim: not better governance, but the elimination of resistance. Not the rule of law, but the rule of force, dressed in patriotic drag. And in this silence—this deliberate disabling of dissent—they call it peace.

The Crumbling Safety Net and the Logic of Attrition

What we’re witnessing now isn’t policy drift. It’s not incompetence. It’s not gridlock. It’s strategy—a deliberate, accelerating erosion of the collective safety net through calculated cuts to Medicaid, SNAP, the CDC, NIH, OSHA, reproductive health services, vaccine programmes, even fluoride in drinking water. These aren’t isolated adjustments. They are systemic extractions, designed to starve the public into submission, to withdraw state care until people no longer expect it. Until they forget it was ever a right.

This isn’t a rollback to some earlier, leaner time. It is counter-revolution by attrition—death by spreadsheet, hunger by policy, suffering by design. And it is always justified the same way: we can’t afford it. The budget’s tight. Belt tightening. Efficiency. But what is austerity if not starvation disguised as governance? What is the systematic withdrawal of care if not the slow violence of abandonment, repackaged as fiscal prudence?

Lenin named this for what it was over a century ago in The Agrarian Programme of Social-Democracy: pseudo-reform. The liberal fantasy that a system built on exploitation can be patched, softened, made kind. That a little redistribution—some crumbs swept off the edge of the landlord’s table—might satisfy the starving and preserve the feast. But crumbs are not a meal. A clinic that’s 50 miles away and only open two days a week is not healthcare. SNAP benefits that don’t last the month are not food security. Free school lunch with no safe place to sleep is not a safety net.

These policies aren’t failed attempts at care. They are successful attempts at pacification. Relief as ration. Just enough to keep revolt at bay, never enough to allow repair or rest. And in the face of rising inequality, climate catastrophe, pandemics, and manufactured scarcity, this “managed neglect” has become the state’s central function.

And the worst of it? They still call it reform. They still frame it as tough choices and necessary modernisation. But this is not modernisation. It’s extraction without end—the dismantling of the public so the private can feed. The slow-motion replacement of solidarity with servitude. It is what happens when government no longer sees its people as a collective to be cared for, but as a population to be sorted, squeezed, and sold.

Lenin warned us: a concession is not a transformation. A system that steals your home and then offers a tent is not reforming. It is rehearsing new methods of control. And every spreadsheet line that erases a clinic, cuts a benefit, closes a centre—that’s not bureaucracy. It’s a decision. It’s a death sentence with a header row.

Reformism Is a Mirage—Theory Is the Map

Reform is the mirage that keeps the weary walking—toward nothing. It flickers in the heat of collapse, promising just enough hope to delay reckoning. But as Lenin made brutally clear, reform always capitulates when pressured. It doesn’t serve to transform the system—it exists to preserve it. The moment the interests of capital are at stake, reform folds. Concedes. Retreats. It becomes the velvet glove over the iron fist.

And nowhere is this more obvious than in the United States, where the Democrats—held up by many as the last line of defence—spend their energy preserving the shells of broken institutions, mistaking the appearance of governance for the substance of resistance. They do not build rungs. They retweet slogans. They do not map the future. They fundraise on the ruins. Their strategy is compromise; their compass is donor comfort. And all the while, the ground continues to give way.

You cannot climb out of collapse with talking points. You need rungs. And theory is the rung. It’s the ladder. It’s the scaffold that makes any kind of upward movement possible. The poster got it right—climbing takes vision, effort, structure. Not centrism. Not nostalgia. Not another committee hearing.

But here’s the brutal generational truth: that scaffold was already half-built, and then it was dismantled. Boomers came of age in a time when state college was either free or shockingly affordable. Healthcare was expanding. Union wages still meant something. The social contract wasn’t perfect, but it existed. Gen X watched it erode—silent witnesses to the beginnings of the clawback, aware enough to grieve it but rarely empowered to stop it. Millennials and Gen Z? They were handed debt as inheritance and told the theft was normal. Told it was just how things are.

Most young people don’t even know college was once free. They’re shocked when told. And why wouldn’t they be? The system has done everything in its power to erase that memory—because memory, like theory, is dangerous. It reminds people that things were deliberately taken. That tuition didn’t rise by accident. That debt is not a necessity but a mechanism of control. That the present state of things is not a natural evolution. It’s the result of policy decisions made by people in rooms—and funded by people in boardrooms.

Reform won’t reverse this. It was never meant to. It exists to manage decline, not to end it. That’s why the future isn’t coming from inside the institutions. It’s coming from the outside—from the ones climbing still, hands on theory, eyes on horizon, refusing to believe the mirage and building anyway.

The Poster Revisited: Climbing Through Collapse

The poster lingers. Not because it offers comfort, but because it refuses to lie. At its centre, a tower of books—solid, weighty, foundational. People are climbing them, one rung at a time. Not flying. Not falling. Climbing. Together. And the city on the horizon, radiant and geometric, does not promise utopia. It promises orientation. It says: there is a way. There is always a way—if you know where to look.

That’s the split it shows so clearly. Below: the figures trapped in the village, heads down, bodies bent by the weight of surviving. Above: the ones who chose to climb. Not because they’re better, not because they’re special, but because they found the ladder. Because they knew to look for it. And that ladder isn’t metaphorical. It’s not an abstract hope. It’s theory—structured, rigorous, collectively developed insight into how the system works and how it can be undone.

The books themselves? They still exist. They haven’t been burned, not yet. You can find them, free and unabridged, online and in libraries and community archives—Marx, on how capital concentrates and consumes; Lenin, on what pseudo-reform does to revolutionary momentum; Mao, on the contradictions inside the people and the importance of organising where you are; Ho Chi Minh, on liberation as pedagogy; Frantz Fanon, on the psychic violence of colonialism and the necessity of reclaiming selfhood through struggle.

And further still: Castro, explaining why imperialism can never be trusted to deliver peace; Malcolm X, on the dangers of liberal delay and white moderation; Martin Luther King Jr., in his final years, calling out capitalism, militarism, and white supremacy as three heads of the same hydra—and being assassinated not long after; and Chairman Fred Hampton, just 21 years old, executed in his sleep by the state for the crime of feeding children, building clinics, and daring to unite poor Black, white, and brown communities under a shared vision of revolutionary solidarity.

And let us not forget the revolutionary women—so often sidelined in mainstream retellings, yet central to any honest canon of liberation. Claudia Jones, who taught us that “the triple oppression of race, class, and gender” is not a footnote, but a frontline. Assata Shakur, whose survival and clarity cut through state repression with unwavering force. Angela Davis, whose lifelong scholarship and activism tether abolition to global liberation struggles. Leila Khaled, who refused to be cast as passive witness to imperial violence. Gloria Anzaldúa, who theorised the borderlands not just as a geography but as a mode of survival. These women weren’t working in the margins—they were the margin, pushing outward, tearing open space for the rest of us. They appear here not because they are secondary, but because we should always save the best for last. And because any map that excludes a feminist lens is not a map—it’s a trap. Their voices insist that revolution without gender justice is no revolution at all. That theory divorced from embodiment, from care, from kinship, will never be enough to climb.

This is the canon they warned you away from. Or worse—filtered out entirely. Not just dismissed, but algorithmically distorted. Leila Khaled becomes a terrorist, not a freedom fighter. Chairman Fred Hampton, a gang member, not a visionary organiser. Ho Chi Minh, the faceless enemy, not the anti-colonial strategist who fed and educated his people. The system doesn’t just hide their words—it repackages them as threats, detours, irrelevancies. But these voices speak with stunning clarity to the crises we’re living through. They name the systems that structure our oppression, and they refuse to let us pretend we didn’t know. These texts aren’t relics. They’re waypoints. And every one of these people—mislabelled, misremembered, misunderstood—had one thing in common: they saw the structure. And they tried to help us climb.

But very few are reaching for them. Not because we don’t care. But because capitalism has trained us to seek solutions in consumption, not in study. In scrolling, not in strategy. And that’s no accident. Because if more of us read Marx, we’d see how manufactured our misery is. If more of us read Fanon, we’d understand why liberation has to be total. If more of us read Malcolm, we’d stop waiting for permission.

If more of us read King in full—not the sterilised soundbites, but the speeches and strategies that actually got him killed—we’d see the truth behind the myth. It wasn’t dreaming that threatened power—it was organising. It was the Poor People’s Campaign, his radical push to unite Black, brown, and white working-class people in direct confrontation with capitalism and empire. That’s what made him dangerous. And it’s no coincidence that just over a year later, Chairman Fred Hampton was doing the same—building the Rainbow Coalition, feeding children, opening clinics, bridging communities deliberately kept apart. That’s what got him killed. The authorities didn’t fear their anger. They feared their success. Their ability to turn shared struggle into shared power.

“Only from the heights of theory…”—not because theory alone will save you, but because without it, you’re stumbling through the wreckage with no map and no names. You’ll feel the walls closing in, but not know who built them—or how they’re maintained. Theory gives you orientation. It names the machinery. It shows you where the exits might be. It’s not an escape plan, but a toolset. It offers leverage, where once there was only weight.

If you don’t climb, you will be crushed. If you can’t trace the structure, you’ll be swallowed by it. And no one is coming to lift you out. But the ladder is still there. The books are still waiting. And across the world, in every shadowed corner of empire, others are already climbing. Always.

Final thoughts …

They’ll dismiss me without reading a word. That’s how it always goes. “Oh, they’re trans. Autistic. Clearly delusional.” Or the classic smear: “Marxists want to take your toothbrush.” It’s never, read for yourself. Never, study and decide based on evidence. It’s character assassination as deflection, a refusal to engage with the substance because the substance threatens too much. And what’s most damning is how many people—especially on the far right—choose not to know. They don’t want to read Marx, or Lenin, or Fanon, because they’ve been told not to. They’re warned, like children from fire, that the text itself is dangerous. That touching it might contaminate them.

Even sadder are the evangelicals, many of whom condemn people like me with a certainty rooted not in scripture but in hearsay. How many have actually read Leviticus? How many have wrestled with the text, the context, the contradictions? The Tanakh doesn’t say Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed for queerness—it names their sins as selfishness, arrogance, cruelty, and the abuse of strangers. Their crimes were economic and social, not sexual. But that reading doesn’t serve the agenda. So the narrative shifts, simplified and weaponised, repeated until it calcifies. Not truth, but political convenience wearing theological drag.

Here’s the thing: I have read. The Bible. The Qur’an. Marx. Engels. Lenin. Davis. Anzaldúa. Minh. Not because I was trained to, or because school led me there. Quite the opposite. I arrived at literacy late—late in the way only an autistic, gestalt-processing, alexithymic kid can arrive—through the side door, years behind my peers, carrying fragments of language and intuition but no consistent map. For so long, reading felt like trespassing into a world that wasn’t built for me. But when it finally clicked—when the words stopped floating and started fitting—it was like a light came on in a room I hadn’t known I was sitting in.

And then I read. And read. And with every page, something else fell away: the soft lies of state curricula, the myth of meritocracy, the revisions passed off as truth. I realised most of my schooling had been propaganda dressed up as common sense. And it was my grandmother—my fierce, sharp-tongued, Scottish-flavoured Marxist grandmother—who became my waypoint. She’d been telling me the truth all along. About power. About class. About solidarity. But growing up, it was everyone else—teachers, neighbours, the TV—that made her out to be the one who was wrong. Who was extreme. Who just didn’t understand the world.

The joy, once I could read for myself, was not just in learning, but in unlearning. In watching the lies crumble. In turning the page and finding her voice again—echoed in Marx, in Fanon, in King, in Davis. Realising that what she said wasn’t fringe. It was foundational. That she hadn’t been misinformed—she’d just been early. And in a world committed to keeping people ignorant, being early looks like heresy.

What I offer here isn’t belief. It’s a traceable path through text and structure and history. Marxists won’t ask you to follow blindly. We’ll tell you to read. To think. To argue. To dig. And most of us will hand you the tools for free. As I’ve done here—with links to the Marxist Internet Archive, where the canon sits, unabridged and unpaywalled. Because unlike those who govern by fear, we don’t fear knowledge. We grow stronger the more we share it.