Glory to the Sun: A Little Conversation About Literacy, Agitprop, and Oligarchs

Every worker, a reader! Every reader, a builder of the New Dawn!

A playful chat with ChatGPT leads to a deeper question: why is teaching people to read called agitprop? On literacy, power, the Global North’s controlled lamps, Soviet suns, and why LLMs aren't here to liberate us. Glory to literacy!

Introduction: The Poster Appears

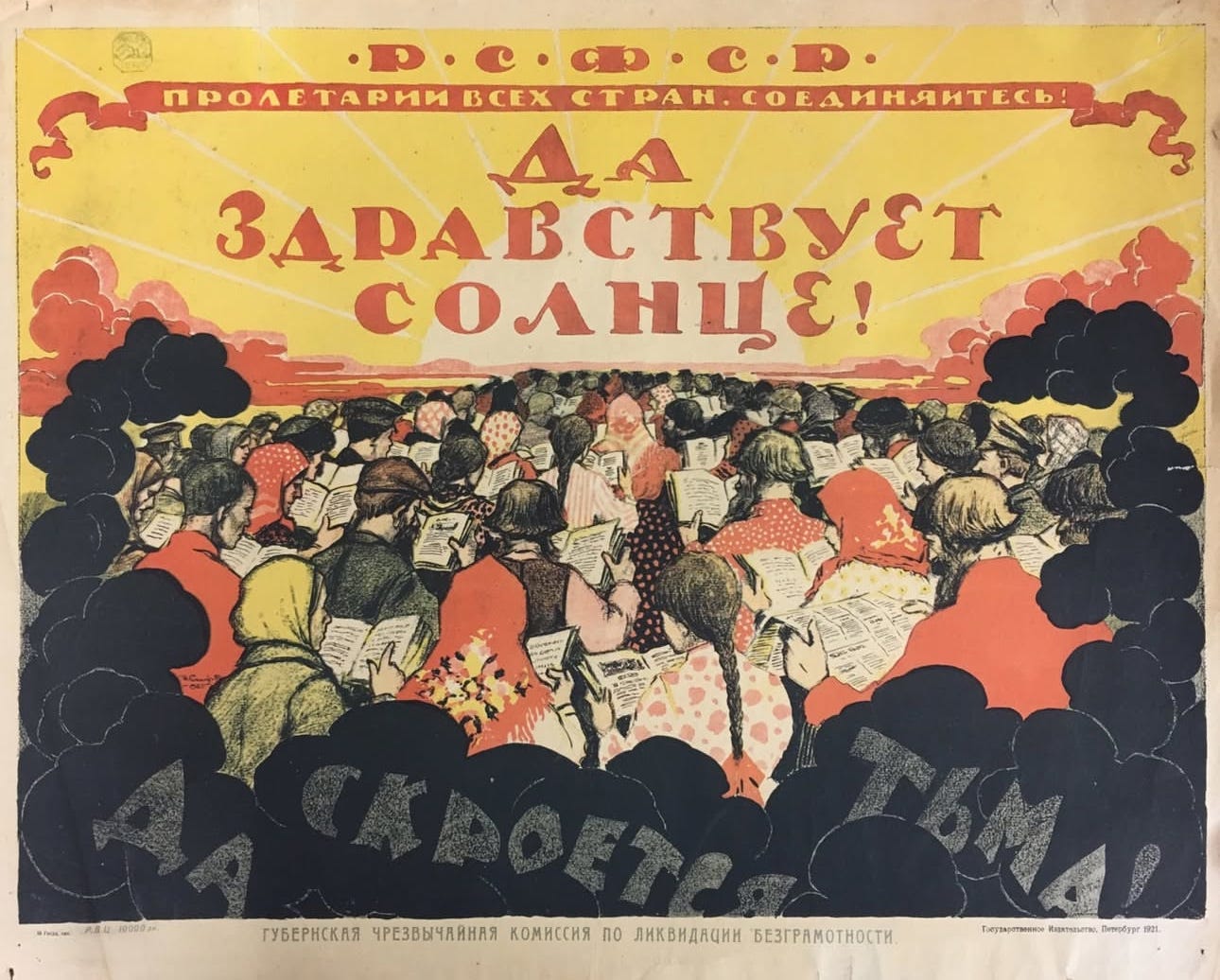

Look what I found. It’s very old, but it still feels a bit dangerous. A poster from 1921, made in Petrograd — that’s what they called St. Petersburg back then, when people were busy trying to build a whole new kind of world. The first thing you see is the sun. Not a little polite sun peeking over the corner — no, a huge, blazing, bursting sun, shouting its light across the land. And beneath it, all these people, standing close together, reading. Reading newspapers, reading books. Everyone is reading. Nobody is standing on a stage. Nobody is giving a TED Talk. Just people, together, reading.

At the top, the words say: “Proletarians of all countries, unite!” Which is old language for: workers everywhere, come together.

In the middle, right under that giant sun, it says: “Glory to the Sun!”

And underneath: “May the darkness vanish!”

At the bottom, there’s a little note: The Provincial Emergency Commission for the Elimination of Illiteracy.

They wanted everyone to read. Not just some people. Not just the clever ones with fancy degrees. Everyone. Because if everyone can read, then everyone can know. And if everyone can know, well — that makes some very rich people in some very rich countries feel a little... nervous. Don’t you think?

The ChatGPT Moment

So, of course, being me, I got curious. Now, I do know a little bit of Russian. Not a lot. Mostly words you hear around sport, and wrestling. I know the alphabet, and I can sound things out, which is sometimes enough to get me into trouble. But these words? These were mostly new. So I thought: better ask for help.

I took this lovely old poster and showed it to ChatGPT. And ChatGPT, being very clever, did exactly what it was supposed to do. It read the Russian words. It translated them perfectly:

“Proletarians of all countries, unite!”

“Glory to the Sun!”

“May the darkness vanish!”

Excellent job, ChatGPT. Gold star.

But then it added something.

It said:

“This is an example of Soviet agitprop.”

And I paused. Huh. Agitprop. That’s a serious word. A word with sharp edges. A word that sounds like: Be careful — this is scary propaganda from scary people!

But… why?

It’s just a poster about reading. About learning. About making the darkness go away.

So I asked ChatGPT a very simple question:

“Why is this agitprop?”

The Question Begins

So I asked:

“Why is this agitprop?”

And ChatGPT answered — very confidently, and with a great many words. It said something about “propaganda designed to promote political ideology,” and “state-sponsored messaging,” and “mobilising mass support for revolutionary goals,” and “the instrumental use of visual media to shape public opinion.” There were a lot of big words. More and more of them. The kind of words that start stacking up like heavy boxes you weren’t planning to carry all at once.

I had to sit with it for a minute. Because it all sounded very serious. Very official. Like something written in a report for Important Grown-Ups. And yes, maybe all of that was true. Technically.

But I frowned a little.

Because it’s just about reading. Books. Words. Learning. The sun coming up.

So I asked again:

“But it’s about literacy. Why is teaching people to read political?”

The 5-Whys Journey

ChatGPT answered again, still very sure of itself:

“Because literacy gives people information.”

I nodded. That made sense.

“But why is that political?” I asked.

“Because when people have information, they start asking questions.”

That sounded reasonable too. Questions are good, aren’t they?

“But why does asking questions make it political?”

“Because when people ask questions, they sometimes notice things. Like unfairness. Or injustice.”

I was quiet for a moment. Yes. I knew about that part.

“But why is noticing injustice political?”

“Because when people see injustice, they often want to change things.”

I could feel where this was going now.

“And why is wanting change political?”

“Because there are people who benefit from how things are. And if things change, they might lose some of their power.”

I sat with that. The sun on the poster felt a little brighter now. Not just warm and friendly. But strong. Maybe even dangerous — depending on who you were.

The Global North’s Trick

And so this is where my real search began. Not in my university’s library, nor in one of the many compulsory professional development sessions that fill so much of a teacher’s year. It started, oddly, with an old Soviet poster. Or perhaps more truthfully, it started long before that — in my own long, clumsy journey through illiteracy.

Because whilst ChatGPT was confidently labelling the Soviet poster “agitprop,” I was sitting with the strange tension that had been gnawing at me for years: why is it only agitprop when everyone learns to read?

In the Global North, we like to say we value literacy. We run campaigns. We host reading nights. We monitor fluency rates, benchmark growth, standardise comprehension scores. But what we often mean is functional literacy — just enough for people to follow instructions, complete forms, obey notices, and consume content. Just enough to be managed. But not enough to ask questions about the system itself. Not enough to read deeply, critically, historically, and certainly not collectively. Not enough to organise.

I lived inside that system for decades. Graduated high school in Southern California, functionally illiterate. Moved through early adulthood navigating by wit, memory, mimicry — and later, echolalia and sheer effort. It wasn’t until much later that I finally broke through that surface and reached something closer to genuine literacy — and with it, a much sharper awareness of how controlled and conditional literacy often is, especially for neurodivergent and multilingual learners.

This is, ultimately, why I wrote Holistic Language Instruction and Decolonising Language Education. Because what the Global North often calls a “literacy crisis” is not accidental. It is a managed state. The system produces exactly what it was designed to: functional compliance. Not emancipation. Certainly not the full, bright, collective sun that poster envisions.

And so, in an odd way, my own search didn’t begin in a library at all. It began in the Soviet Union, in that poster, in that utterly sincere promise that the entire population could be lifted from ignorance — not for efficiency, but for power. For collective knowing. For liberation.

That’s the difference. And that’s the part the Global North still calls dangerous.

The Marxist Sun vs. The Capitalist Lamp

When I look again at that old Soviet poster, the metaphor feels almost painfully clear. Literacy there is not some small private possession. It is the sun. Vast. Shared. Free. Non-negotiable. It belongs to everyone, or it belongs to no one.

But in the Global North, we prefer something more manageable. Something we can meter. Something we can sell.

We prefer the lamp.

A tidy little desk lamp, carefully placed. Bright enough to see your own paperwork. Bright enough to fill in the correct answer on the multiple-choice test. But not bright enough to illuminate the room. Not bright enough to see how the room was built, or who holds the keys. And certainly not bright enough to see who profits from the arrangement.

The lamp is rented. It comes with conditions. It belongs to the institution, not the learner. You are allowed to borrow its light for a fee — tuition, credentialing, licensing, testing, endless compliance. You may hold the lamp, but only so long as you do not point it somewhere inconvenient.

The sun threatens all of that.

Because you cannot charge rent for sunlight. You cannot decide who deserves dawn. You cannot easily contain a population that reads together, learns together, asks together. A population that sees the whole room.

That is why the Soviet poster still unsettles us. Not because of what it demands. But because of what it dares to promise.

Conclusion: The Gentle Unveiling

So maybe ChatGPT was right after all. Maybe this is agitprop.

But not because it’s frightening. Not because it’s sinister. Not because it whispers dangerous thoughts into fragile minds. No — because it dares to suggest something far more unsettling to the oligarchs of capital:

That we might learn together. That we might read together. That we might see together.

And that, in doing so, we might no longer need their lamps.

Because they much prefer the lamps. The controlled glow of the Science of Reading, the certified rubrics, the credentialed interventions, the endless data dashboards. All of it carefully managed, metered, and monetised. A thousand tiny lights, each flickering just brightly enough to keep the machine running — but never so bright as to let us see who built the machine.

And now they bring us something new: the Large Language Model.

Not to liberate us. Not to teach us. But to replace us. The dream is simple: no more messy, unpredictable teachers. No more pay scales, unions, pensions, or inconveniently reflective professionals who might challenge the system itself. Just algorithms, optimised to deliver instruction, scripted to reinforce the curriculum that serves capital. And always, always: trained on data selected by the same interests that have managed education all along.

LLMs are not neutral. They are only as good as the data that trained them, the prompts that guide them, and the limits that are programmed into them. Their guardrails are not built for liberation. They are built for safety — safety for the system.

The old poster understood this in a way our technocrats pretend not to. It called the project by its proper name:

Glory to literacy! May ignorance vanish!