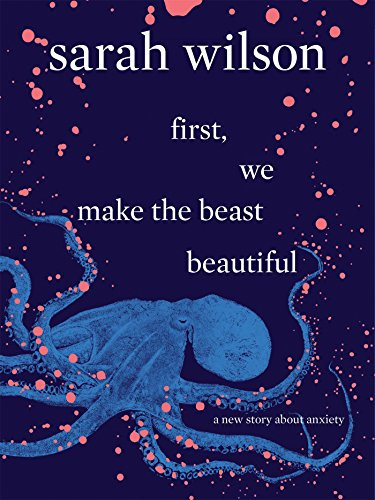

Of all the things I thought I might find solace in, anxiety was not one of them. Yet First, We Make the Beast Beautiful by Sarah Wilson, with its evocative title and deep, winding exploration of anxiety as something to be worked with rather than against, offered me a perspective that felt both radical and intimately familiar. The book does not present a neat, step-by-step guide to conquering anxiety—because, as Wilson argues, anxiety is not something to be vanquished. It is a part of us, a voice calling for attention, a force that, when understood, might actually be woven into a meaningful life. She blends science with philosophy, memoir with practical insight, crafting a narrative that is as fragmented and looping as an anxious mind itself.

I was drawn to the book immediately, not just because anxiety has been a constant companion in my own life, but because I have long found comfort in so-called “eastern” philosophies and practices—particularly those that frame suffering not as a curse, but as something to be worked with, understood, even accepted. It is a sensibility that has always made more sense to me than the rigid medical frameworks I have been subjected to, the ones that sought to diagnose, pathologise, and medicate without ever really seeing me. As someone who was diagnosed late in life, and only after years of being misunderstood by a psychiatric system that had no language for autism, for gestalt processing, for the way my mind assembles and experiences the world, Wilson’s approach felt like something akin to recognition.

There was also the simple fact that I love reading now. I say now because literacy was something I had to claw my way into late in life, something I had to claim for myself after years of struggling to fit into an education system that was not designed for the way my brain works. Books are a joy to me precisely because they were once inaccessible, and in that way, Wilson’s writing resonated even more. Her reflections on anxiety, on the ways our minds shape and reshape the world, on the stories we tell ourselves to survive, felt like an invitation—an acknowledgment that the beast need not be slain, only understood.

The Book Review: ‘First, We Make the Beast Beautiful’

Sarah Wilson does something quite extraordinary in First, We Make the Beast Beautiful: she refuses to treat anxiety as a malfunction to be corrected. Instead, she suggests that anxiety is an integral part of human existence, a feature rather than a flaw (hmm, where have we heard something like this being said?). This is not the standard self-help approach, nor is it a clinical dissection of symptoms and treatments. It is, instead, a deeply personal and meandering exploration of what it means to live with a mind that never settles, a mind that questions, anticipates, and loops endlessly in its search for meaning and certainty. Rather than presenting a cure, Wilson invites us to consider the possibility that anxiety is not something to be eradicated but something to be understood, even embraced.

She moves fluidly between memoir, science, philosophy, and spirituality, pulling together insights from Buddhist teachings, Stoicism, and modern psychiatry, whilst weaving in conversations with monks, therapists, and fellow anxiety sufferers. She does not treat these disciplines as separate entities but rather as overlapping lenses, each offering a different perspective on the same experience. There is no single answer, no definitive solution—only an ongoing conversation with the self, a practice of sitting with discomfort rather than fleeing from it.

At the heart of the book is the idea that, before we can make the beast beautiful, we must first make the beast. Anxiety, Wilson argues, is not an enemy to be defeated but a part of ourselves that demands attention, care, and—most radically—acceptance. She acknowledges its destructiveness, the sleepless nights, the spirals of self-doubt, the ways it can derail a life. But she also asks: what if anxiety is not a failing? What if, instead, it is a sign of deep engagement with the world, a heightened sensitivity that, when channelled rather than resisted, can lead to something meaningful?

This is what makes Wilson’s approach so resonant. It does not dismiss the suffering anxiety brings, nor does it promise an easy path forward. Instead, it offers a shift in perspective, an invitation to see anxiety not as something to be ashamed of but as something that, in its own strange way, might just hold the key to a more present, more creative, and more deeply felt life.

A Personal Interpretation Through an Autistic Gestalt Processor Lens

Sarah Wilson’s approach to anxiety in First, We Make the Beast Beautiful resonates deeply with me, not just as someone who has lived with anxiety their entire life, but as an autistic gestalt processor—someone whose mind doesn’t break things down into steps or sequences but instead processes experiences in wholes, in complete, interconnected units of meaning. Readers familiar with my work will know that I have written extensively about this cognitive style, the way it shapes my perception of the world, and how it intersects with my experiences of anxiety (use the search function to find all the articles). Wilson’s perspective offers another layer to that understanding: what if, rather than treating anxiety as an aberration, we considered it an essential part of how some minds navigate uncertainty, probability, and the search for coherence?

For autistic people, anxiety is often not a passing emotional state but an embedded part of how we experience the world. It is not merely a response to stressors but a structural component of cognition, particularly for gestalt processors like myself. My brain doesn’t assemble understanding piece by piece—it seeks complete scripts, entire frameworks that make sense of a given situation. When faced with unexpected events, when my mind cannot immediately locate the correct gestalt, anxiety escalates into a frantic internal search, a runaway probability calculation where every possible scenario is weighed, adjusted, and re-evaluated until the system crashes into panic.

Wilson’s approach to anxiety—seeing it as an integral part of one’s experience rather than a pathology to be eliminated—offers a crucial reframe. Rather than viewing my own anticipatory anxiety as an unwelcome burden, I can recognise it as my brain’s attempt to create order from the unknown, to prepare me for the unpredictability of life. But unlike Wilson, whose approach to anxiety is largely shaped by mindfulness and an intuitive acceptance of uncertainty, my experience is complicated by a neurocognitive style that resists ambiguity. Where she finds peace in allowing the unknown to exist without resolution, my brain is wired to resolve—to find the right script, to complete the pattern, to bring the gestalt into being. This is where my experience diverges, and where my anxiety, particularly in the form of nocturnal panic attacks, takes on a shape that is both overwhelming and, paradoxically, generative.

Wilson talks about making the beast beautiful, but for me, the act of making the beast at all—constructing words, forming coherent narratives from the chaos—is what makes it beautiful. My writing, in many ways, is the result of this process, the tangible form of the cognitive storm that rages when my brain is trying to make sense of something it cannot yet hold. It is a relentless process, often exhausting, sometimes destructive, but it is also the source of everything I create. Anxiety, in this context, is not just something I endure—it is something I shape, something I translate into meaning. Wilson’s book affirmed what I had already come to understand: the beast does not have to be fought. It can be given form, given voice, given beauty in its own right.

Navigating Anticipatory Anxiety and Panic Attacks

Anticipatory anxiety is a relentless force, one that I have come to understand not as a fleeting emotional state but as a deeply ingrained cognitive process—an inescapable part of how my brain, as an autistic gestalt processor, navigates the world. It is not a vague, nebulous worry about what might happen; it is a full-scale mental operation, not unlike the way large language models generate responses. My brain, like an LLM, doesn’t simply recall a pre-existing answer—it runs an immense, resource-intensive process, predicting, weighting, and assembling the most statistically probable script for any given scenario. Every interaction, every unexpected moment, triggers a cascade of real-time calculations, searching for the best possible outcome, testing variations, refining responses, constructing entire conversational pathways before a single word is spoken. And just as LLMs require staggering amounts of compute power to function—vast networks of servers running at full capacity, generating immense heat that demands constant cooling—my brain consumes an enormous amount of cognitive energy to reach these conclusions. The result is the same: exhaustion, depletion, a desperate need to recover from the sheer intensity of the process. I often think about the unseen cost of artificial intelligence—the water it takes to cool the servers, the energy expended to produce a single coherent response—and recognise myself in that equation. The toll it takes on me, the mental and physical burnout, is not so different. The problem, of course, is that the world is not scripted. And when the unexpected happens—when the necessary gestalt is missing, when my brain cannot immediately retrieve the correct framework—the entire system begins to collapse.

I see this same relentless processing in my students, particularly those who, like me, are gestalt language processors. This isn’t an exclusively autistic experience—many neurodivergent students, and even some from the neuro-majority, share this cognitive pattern. Yet the systems designed to assess knowledge, particularly standardised tests, are built for a fundamentally different kind of thinker. These exams assume a linear approach: read a question, retrieve a discrete answer, move on. But our minds don’t work like that. We don’t just pull information from a neatly labelled mental file—we search for wholes, patterns, contextual meaning.

The disconnect between how we process and how we are expected to perform creates an overwhelming internal storm. I see it in my students’ shifting eyes as they scan for a familiar script, in the tension in their bodies as they wrestle with a question that demands an answer they can’t retrieve in isolation. It’s not that they don’t know—it’s that the system demands a mode of thinking that doesn’t align with how their brains assemble knowledge. The effort it takes to bridge that gap drains them, consuming more spoons than they have to give.

I recognise their frustration because I live it. The same relentless probability engine that runs in my brain, assembling possible responses, determining the “best” outcome, is at work in them. In an environment that doesn’t account for our processing style, this isn’t just exhausting—it is cognitively expensive, an all-consuming demand that pulls energy from every other function. The sheer effort of trying to conform to a system not built for us leaves little room for anything else.

For me, this mental storm does not stop when I sleep. If anything, it intensifies. Nocturnal panic attacks are where my brain’s relentless need to resolve uncertainty takes its most brutal form. I do not wake in fear of something unknown—I wake because my brain has already run the calculations, because it has spent the night assembling a complete gestalt, a fully formed script for a crisis I did not know I was preparing for. I wake in the aftermath of an unconscious process I had no control over, already holding the answer to a question I never asked. My body reacts as if the crisis is unfolding in real time—heart racing, breath shallow, limbs tense—because my brain does not distinguish between simulation and reality. By the time I am fully awake, the conclusions have already been reached, the decisions made, the panic set in.

But more and more often now, when the storm recedes, I find something else waiting for me: a fully written poem, formed in the depths of sleep, as if my mind had been working through something I didn’t even know I was wrestling with. The words arrive fully shaped, a resolution of sorts, not to the panic itself but to some deeper uncertainty beneath it. It is as though my brain, after tearing itself apart in the search for meaning, stitches something back together in the quiet moments before I wake.

Wilson’s reframing of anxiety as something to be worked with rather than against has helped me see these episodes in a different light, but the reality remains: my brain will always seek resolution. It will always try to close the loop, to find the right script, to make sense of the unknown before it can rest. Lately, that process has taken on an even stranger form. More often than not, I wake not just with the remnants of panic, but with something fully formed—a poem, a passage, a string of words that somehow resolve a question I didn’t know I was asking. And this time, my mind decided, in the midst of sleep, to review a book I first read years ago, reconciling Wilson’s long-absorbed words with the newer revelations I’ve written about in recent years.

It’s as if my unconscious self, still running its relentless calculations, determined that now was the time to reprocess First, We Make the Beast Beautiful—to hold it up against everything I have since learned about my own mind, about being autistic, about gestalt processing, about the way my anxiety is not just a state but a system, a force that dismantles and reconstructs meaning—and even how all of this presents in my newly energised trans system. And whilst this endless internal machinery often leads to overwhelm, to shutdown, to nights spent in panic, it is also, paradoxically, the very thing that drives me to write. The words that come from these moments—the clarity that emerges from the storm—are what allow me to make the beast beautiful.

The Inadequacy of Psychiatric Systems in the Context of Autism

Given all of this—how my brain processes information, how it constructs meaning, how anxiety is not just an emotional response but a full-scale cognitive operation—it is no surprise that psychiatry, as it exists today, was never built for people like me. The system assumes a kind of baseline neurotypicality, an expectation that patients can articulate their experiences in a way that aligns with clinical frameworks, that they can engage with therapeutic models designed around analytical, sequential thought. But what happens when someone like me back then—a gestalt processor, an undiagnosed autistic person, someone who doesn’t piece together thoughts step by step but instead experiences them as wholes—is thrown into that system? The answer, I learned in my twenties, is that it goes very badly.

I was placed in talk therapy at a time when I did not even have the language to describe what was happening to me. I did not yet know I was autistic. I did not yet have the words for gestalt processing. And without scripts to rely on, I simply had no way to engage. I would sit in a chair, silent, completely shut down, unable to respond in the way the system expected. But instead of recognising that I was in autistic shutdown, instead of understanding that I literally could not access the language they were demanding, therapists and psychiatrists saw my silence as defiance. As avoidance. And when a patient is big—when they are visibly strong, a trained athlete, a martial artist—those misinterpretations carry consequences. I was perceived as a threat when I was simply overwhelmed. My lack of engagement wasn’t passive resistance, it was neurological paralysis, but there was no framework for that in the clinical model. So the system responded the way it always does: it escalated.

When therapy failed to “break through,” the solution was medication, prescribed under the wrong premise, with disastrous results. The dosages increased when I didn’t improve. The assumptions about what was happening to me were never questioned. The result was a chemical straitjacket—a thick, unnatural slowness that wrapped around my thoughts, dulling everything, yet somehow making the panic worse. I was bubble-headed, incapable of forming coherent scripts, unable to construct the internal structures I relied on to function. My mind, usually so relentless in its calculations, could not think its way out. Instead, it overheated. The panic did not subside—it amplified. I was trapped, internally screaming, unable to form words, unable to navigate the confusion of my own mind.

The night terrors were the worst. They weren’t just bad dreams; they were a waking horror, a state of being pulled from sleep into a reality that was only almost real, liminal states / hallucinations layered over the world, my body reacting in full fight-or-flight before I was even conscious enough to understand what was happening. The medications that were meant to dull the anxiety instead turned it into something nightmarish, something I couldn’t escape even in sleep. I was lost in it.

The worst part was the frustration—not just at the system, but at myself. At the time, I had no language for what was wrong. I couldn’t explain why the therapy didn’t work. I couldn’t explain why the medications made things worse. And so I blamed myself. I internalised the idea that I was broken in some fundamental way, that I was resistant to treatment, that I was the problem (watch out when alexithymia and hyper-empathy collide with professional gaslighting …). And in that misalignment, in that misinterpretation of what was happening to me, I lost most of my twenties. Years that should have been spent building a life were instead spent trying to survive treatments that were never meant for someone like me.

It wasn’t until much later—after I learned I was autistic, after I understood gestalt processing, after I finally had the words for what had always been happening in my mind—that I could begin to unravel the harm that had been done. Psychiatry didn’t fail me because it was malicious. It failed me because it didn’t know me. It didn’t have the language, the frameworks, the understanding of how minds like mine operate. And when a system doesn’t understand something, it pathologises it. It tries to suppress it. It forces it into models that don’t fit, then blames the person when they don’t respond as expected. That misunderstanding—the fundamental misalignment between the way the system worked and the way my mind functioned—cost me a decade.

Writing as a Beacon of Joy and Understanding

Writing came to me out of necessity, long before I understood its deeper purpose. It was never something I set out to master, nor was it an innate skill that came easily. My relationship with literacy was strained, delayed, an ongoing battle between a mind overflowing with ideas and a language that often felt just beyond my grasp. And yet, when I first began writing, it was as if something within me clicked into place—a bridge forming between my thoughts and the world, a way to make meaning out of the overwhelming flood of information constantly running through my mind. At first, I didn’t see it as anything more than a tool. I was writing to explain, to instruct, to document. But looking back, I see that I was also writing to process, to construct order from chaos, to give form to something that had always threatened to consume me.

My first book, Forensic Photoshop, came together through something like social engineering—a collective effort of thought, experimentation, and open discourse. I was trying to translate my image processing workflow into words, throwing my crude attempts at language at some incredibly smart people, who, in turn, coached me on the precise terminology needed to describe the functions I was performing. It was a process of refinement, of learning how to bridge the gap between what I intuitively understood and what could be clearly communicated to others. In the years leading up to it, I had been blogging about this new forensic discipline that was still in its infancy, one that I was helping to shape. There was no roadmap, no established workflow for using Photoshop in forensic contexts, so I did what felt natural: I started documenting, sharing my discoveries, refining my approach in real time. The book grew from that, not as a grand plan but as an extension of the way I process the world—by assembling information, constructing gestalts, shaping fragments into something whole.

Its release was a revelation. Seeing my book turn into a best-seller, sold on every populated continent, was surreal. Teaching my Photoshop workflow at Adobe HQ in San Jose filled me with a kind of autistic joy that is hard to describe—the sheer delight of transmitting knowledge, of making something make sense to others, of seeing them grasp it and use it. The feeling was electric. This was literacy in motion, a kind of living proof that I could take the raw data of my mind and translate it into something tangible, something that mattered.

That was the beginning. Over the years, as I took on roles in various national boards—whether at NIST’s OSAC, shaping forensic standards, or working on video evidence retrieval and interview room recorder guidelines—I always gravitated toward research and writing. Any time there was a need for documentation, for the structuring of knowledge, for translating complex ideas into something usable, I volunteered. I didn’t yet have the words for why this mattered so much to me, but looking back, I can see it clearly. Writing was more than a skill—it was therapy, a form of occupational and language development that I threw myself into, without even realising I was doing so.

At first, my writing was purely commercial and instructional—technical manuals, standards, non-fiction. I was writing, and that was enough. I was communicating in English, a language that still felt both foreign and familiar, structured yet elusive. It brought me immense joy, not because it was effortless, but because it was possible. For someone whose literacy had been so delayed, so hard-won, every sentence felt like an act of defiance, a declaration that I could shape my own language, on my own terms.

And then, at some point, I began writing differently. The work I do now, on The AutSide and in my short stories and poems, is something else entirely. It is not about instruction; it is about translation—taking the massive, unwieldy pipe of data that runs through my mind and shaping it into something that can be understood. Wilson speaks of making the beast beautiful, and I think that’s what writing has become for me. It is the place where the relentless anxiety, the runaway processing, the overwhelming need for resolution all find structure, form, coherence. It is a way to pull something beautiful from the storm.

I still take an immense amount of time with it, shaping every thought carefully, ensuring the structure holds. The process itself feels paradoxical—limiting in that I must confine my thoughts to words, yet liberating in that I am able to do it at all. English is not native to me, and yet it is the medium I have claimed, a language I have reshaped to carry my meanings, my rhythm, my way of thinking. The process is both grounding and disorienting, comforting and alien at once. It is hard to explain, but perhaps that is the nature of writing itself—a paradox, a translation, a kind of beautiful, necessary imposition of form onto something vast and untamed.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) and the Opening of the Creative Floodgates

When I began hormone replacement therapy, I expected the physical changes, the emotional shifts, the subtle ways my body and mind might recalibrate. But I didn’t expect the floodgates to open—the surge in creativity, the clarity in thought, the way my relationship with language would transform. I knew that HRT had cognitive effects, but I hadn’t imagined just how profound they would be. It wasn’t just that my thinking became sharper; it was that my entire process of expression felt newly aligned, as though something had finally clicked into place.

From the earliest weeks, I noticed the shift. Words that once felt stuck or slow to form now arrived with an ease that was almost unsettling. Writing, which had always been an intensive, deliberate process, became something fluid. Where I used to wrestle with structure—painstakingly arranging ideas, struggling to shape coherence from the noise—now the words came fully formed. It was as though my brain had been running on a faulty connection for years, and HRT had restored the bandwidth, allowing thoughts and language to move freely.

The acceleration was undeniable. Where I once needed extensive outlines and heavy revisions, now ideas arranged themselves in natural sequences, paragraphs unfurling with an intuitive precision that I had never experienced before. Writing had always been a process of translation for me—an effort to extract and refine the chaotic flow of information streaming through my mind into something readable. Post-HRT, that translation process became almost instantaneous, as if my brain and my language were no longer working against each other.

This shift went beyond efficiency; it was deeply transformative. Writing had become been essential to me, a means of structuring my thoughts, of making sense of a world that often felt too fast, too fragmented. But now, it was joyful in a way it had never been before. The raw intensity of my internal processing, which had once led to overwhelming cognitive exhaustion, now found an outlet in words—shaped, coherent, ready to be written down (but, FFS, why all at once …).

HRT didn’t just grant me clarity; it aligned my mind with my expression. It was as though the very architecture of my thought had been corrected, as if the communication centres in my brain had finally been tuned to the right frequency. And the result? A torrent of creativity, a near-constant flow of ideas, stories, articles, poems—things I had always wanted to write but had never been able to pull from the tangled depths of my cognition quite so clearly.

The experience is difficult to describe, because it is both subtle and immense. English, a sewer-drain of a language that has never felt entirely natural to me, now feels more accessible yet more foreign—as though I have stepped into it fully, but from a different vantage point. Writing remains a process that takes time, that requires careful shaping, but it no longer feels like I am clumsily forcing the pieces together. The limitations of language are still there, but they no longer feel insurmountable. Instead, they feel like something I can move through, rather than something that constrains me.

Since starting HRT, my writing has not just improved; it has expanded. My work on The AutSide, my poetry, my short stories—these are not just new projects, they are evidence of a mind finally able to process and articulate without the static that once slowed it down. Wilson writes about making the beast beautiful, but I think, for me, this process has been about something even more fundamental: making the beast speak, fluently, for the first time in my life.

Embracing the Beautiful Beast

For the first time in my life, the beast speaks fluently. The overwhelming, intricate menagerie of gestalts—complex, interwoven understandings that exist more as concepts than as words—has found a voice. Writing has given me a way to translate them, to take what was once an unstructured flood of meaning and shape it into something that can be understood, not just by others, but by myself. It has given me the ability to communicate ideas that once felt impossible to articulate, emotions that existed in an amorphous space beyond language. In doing so, it has given me myself.

This is how I have reframed Wilson’s book to fit my reality. First, We Make the Beast Beautiful is about reimagining anxiety, not as something to be eradicated, but as something to be worked with, transformed. For me, that transformation has been deeply tied to expression—to giving form and language to the forces that shape my cognition. And in sharing this process, I hope others might feel encouraged to do the same—not to copy me, not to copy Wilson, but to take their own beasts, their own experiences, and find the frameworks that allow them to be heard, understood, and honoured.

This is not about eliminating anxiety. I still get panic attacks. I still wake up in the night with my brain running through countless probabilities, trying to script its way into certainty. But what has changed is that I no longer see this process as something I must fight against. I understand it now. I know what it is trying to do, what it is trying to give me. And because of that, I can ride its energy to a less stressful resolution, letting it move through me rather than trying to suppress it. Knowledge of this—of how my brain works, of how my anxiety functions—is a powerful tool in managing my stress, allowing me to work with myself instead of against myself.

This is an ongoing journey, one of self-acceptance and growth through writing. Each piece I write, each poem, each article, each story, is another way of making sense of myself, of turning the chaos into something structured, something meaningful. Writing is not just an act of communication; it is an act of becoming, a continuous unfolding of who I am. And that, perhaps, is what making the beast beautiful truly means—not taming it, not silencing it, but letting it speak in a voice that is wholly, authentically my own.

Final thoughts …

Anxiety is not something I have conquered, nor is it something I wish to. It is a part of me—woven into the fabric of my cognition, shaping how I process the world, how I create, how I understand myself. I no longer see it as an adversary, something to be tamed or silenced. Instead, I have learned to work with it, to listen to what it is trying to tell me, to make it speak in a voice that is wholly my own.

This journey—of writing, of reframing, of understanding—has shown me that the beast is not an enemy. It is a force, a movement, an energy that can be shaped, given structure, given beauty. It is the momentum that carries my words, the engine that drives my art, the restless calculation that wakes me in the night with entire stories formed in the depths of sleep. It has not disappeared, but it no longer consumes me. It moves through me, and I move with it.

For those who also wrestle with their own beasts, who feel overwhelmed by the weight of anxious thought, who wonder if they will ever find a way to translate their own internal worlds into something meaningful—know that you are not alone. Your mind is not broken. It is working, thinking, creating, searching for the shape that will bring it clarity. There is beauty in that process, even when it feels impossible to hold.

If nothing else, I hope my own process—of turning panic into poetry, of riding the surge of uncertainty into language, of making the beast speak—can serve as an invitation. Not to follow my path, nor Wilson’s, but to find your own. To see anxiety not only as something that takes, but as something that creates—art, connection, understanding. To shape it into something that is wholly, beautifully, uniquely yours.

Expat from Værensland, II

I have lived alongside the beast,

its restless pacing the rhythm of my nights,

its breath hot against my thoughts.

For years, I fought to quiet it,

to press its wild limbs into stillness,

to make it disappear.

But it does not die, only changes shape—

the curve of a sentence,

the weight of a poem held between my teeth.

I have learned to listen to its hunger,

to carve meaning from its restless gnawing,

to give it language,

to make it beautiful.

Now, when the beast calls me awake,

I greet it with ink, not fear.

It does not own me, but I no longer run.

I let it speak,

and in doing so,

I have found my own voice.

this feels so close....pathologizing human complexities........is this the way. It hurts

https://open.spotify.com/track/1JcIXOir94YUYBt2cXTzn2?si=9WddfqE8SbSf1t0aD84GRQ